When it was Willie’s turn, he brought it all back home and witnessed like he rarely did when he was the star of the Willie Nelson Show. “Sister Bobbie and I have been going to this church ever since we were born,” he said to the gathering. “I don’t know what persuasion y’all were when you entered this door, but now you’re all members of the Abbott Methodist Church and will be, forever and ever. We’re starting a Department of Peace here in Abbott; we’ve got departments of war everywhere, so go forth and spread the peace.”

Sooner or later, no matter where they’d been or where they were going, the road led back to Abbott, as it did several times a year to a place its most famous native son described as “free as the America that you want.” The population of the small town near the center of the second-biggest state in the United States had neither decreased nor increased. It was pretty much the same. “It keeps calling me back,” Willie said. “You go back to where you feel good. It’s not really a big surprise to me that I can’t wait to get back there again and hang out or ride my bike or run or take off on some of those little roads.”

On the first Sunday morning of July in the year of our Lord 2006, just north of West and not too far from Bug Tussle, Honeysuckle Rose IV and four other buses found their way to the Abbott Methodist Church and surrounded the modest 107-year-old white clapboard church with the humble shake-shingled steeple like wagons around the campfire. The United Methodist congregation of the church that Bobbie Lee and Willie Hugh Nelson had grown up in had dwindled to the point they merged into the larger United Methodist church congregation in Hillsboro. The church building was put up for sale, with a likely fate of being torn down or moved to become a wedding chapel on the highway or a steakhouse in Dallas. Donald Reed, Willie’s classmate from the Class of ’50, called him with a heads up. The asking price for the prettiest building in all of Abbott was $72,000.

“See if they’ll take $2,500 more than they’re asking,” Willie instructed Donald.

An old-fashioned Sunday morning gospel singing celebrated the church’s rebirth. The chapel, which could seat a little more than 100 worshippers, was packed. All 200 folding chairs under tent awnings on the lawn outside the church were filled, its occupants fanning themselves with commemorative fans while watching two giant flat screen video screens showing what was going on inside. Five giant Prevost touring buses surrounded the building, including the one with a side mural of a noble Indian warrior chief on horseback escorting a smaller pony, and the ethereal image on back painted by David Zettner of an eagle’s eyes morphing into the eyes of Willie Nelson.

On the lawn by the tents, a community Sunday supper of fresh food and free bottles of Willie Nelson Spring Water was being readied by members of the Texas Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association and the Austin Spice Company.

Inside, on the platform by the pulpit were Sister Bobbie and her full flowing mane of honey-blonde hair behind the 7-foot Steinway B she played on the road, home again with her brother dressed in his Sunday best with a dark suit jacket over a black oxford shirt, his hair pulled back in a ponytail down to the small of his back—as long as Sister’s—playing the prelude, she on piano, he on guitar, the two of them, playing “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.”

“What a glorious day,” preached Pastor Denise Rogers, opening the service. “Let us pray.” Heads bowed, the congregation prayed. She read from Isaiah 43:1 focusing on the line “I am about to do a new thing, now it springs forth, do you not perceive it? I will make a way in wilderness and rivers in the desert.”

“That is why we’re here today. God is doing a new thing here today in Abbott, Texas,” the pastor said. “These words were written for a group that had been in exile, a larger number who had dwindled down to a few, a remnant that had faith in God.”

When it was Willie’s turn, he brought it all back home and witnessed like he rarely did when he was the star of the Willie Nelson Show. “Sister Bobbie and I have been going to this church ever since we were born,” he said to the gathering. “I don’t know what persuasion y’all were when you entered this door, but now you’re all members of the Abbott Methodist Church and will be, forever and ever. We’re starting a Department of Peace here in Abbott; we’ve got departments of war everywhere, so go forth and spread the peace.”

Holding a lyric sheet, he sang “Precious Memories” as Bobbie played piano and Leon Russell, tucked away in a corner, ever mysterious with white hair, gray and black jacket, black Hawaiian shirt and dark sunglasses, played chords on a small Yamaha. Willie didn’t need a lyric sheet to forcefully sing the next song with the opening lines, “There’s a family Bible on the table, its pages worn and hard to read. …”

Willie introduced his preacher friend from up near Dallas, Dave Rich, who told a story about Willie writing “It’s Not for Me To Understand” back in the mid-1960s. Upon hearing the demo Rich had recorded of the song, Willie jumped from behind a desk and started beating the floor, saying to Pete Drake, “I don’t care if I never get another song recorded, I’m satisfied now.” The song of acceptance and redemption became part of the Yesterday’s Wine song cycle.

He sang “What Happened to Peace on Earth?” solo, then was joined by Paul and Billy and Mickey and Bee for some uptempo gospel with “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” and “I’ll Fly Away.”

Daughter Susie Nelson read the closing statement from the Abbott United Methodist Church congregation affirming “the end of an era is the beginning of another” and that a church is “not a place or building, but the people of God.”

“That’s where we all are today, thank you for coming out and visiting with us today” Willie said, leading into “Amazing Grace” accompanied by piano, harmonica and the whir of locusts in full summer song and the low rumble of five buses idling, punctuated by an occasional warning whistle from a Katy freight train passing through.

The service was captured by television cameras and microphones for the RFD cable television channel dedicated to rural America, local stations in Dallas-Fort Worth and Waco and for KHBR, 1560, “Radio for Your Hometown” the station where Willie Nelson first performed on the radio.

Outside of town along Trlica Road, an expansive blue Texas sky laced with puffy clouds lorded over a landscape in full summer glory with thickets of trees along property lines, clustered around houses, and in groves lining creek and river bottoms wearing their richest greens. What little corn, wheat and sorghum remained in the fields had dried up and withered, but tiny white cotton bolls were beginning to emerge on the cotton plants. Giant sunflowers dappled stretches of the rolling countryside with splotches of bright yellow. Abbott was a slice of American apple pie done up Texas-style.

The good, God-fearing church people along with other town citizens pressed up close to Honeysuckle Rose IV trying to peer through the tinted windows of the touring bus belonging to the local boy made good, alongside representatives of the sheriff’s department and fire department keeping the street clear. All of them appeared to be oblivious to the putrid skunk aroma wafting out of the bus—the telltale sign someone was burning Willie Weed on this fine Sunday morning. The firemen and the sheriff’s deputies were too busy cheering the little man emerging from the church to mind the odor.

Instamatics, 35mm film, digital and cell phone cameras were held high in the air, all aimed at the man slowly making his way into the throng of the faithful crowding the 20-yard path from church door to bus to the sound of cheers and laughter. A noble among his flock, he was one of them. He set off a round of cheers by simply signing the guitar that had been passed over heads in his direction, and another round of cheers as he sent it back over the sea of hands to its owner.

That Sunday morning, Abbott looked, sounded and smelled like Texas. The gathering attracted all shapes, sizes and colors, an estuary of humanity where the sacred mingled with the profane, ebbing and flowing around a solitary man, a Texan’s Texan.

Willie Hugh Nelson was living in the moment, “the only time,” he said, “I can do anything about.”

He had done what he’d always set out to do. “I think I’ve about covered it,” he said with satisfaction. And he was on to the next.

——————–

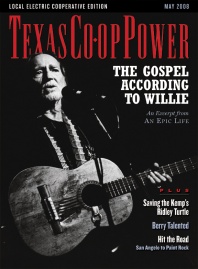

From the book, Willie Nelson: An Epic Life by Joe Nick Patoski. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York, NY. All rights reserved.