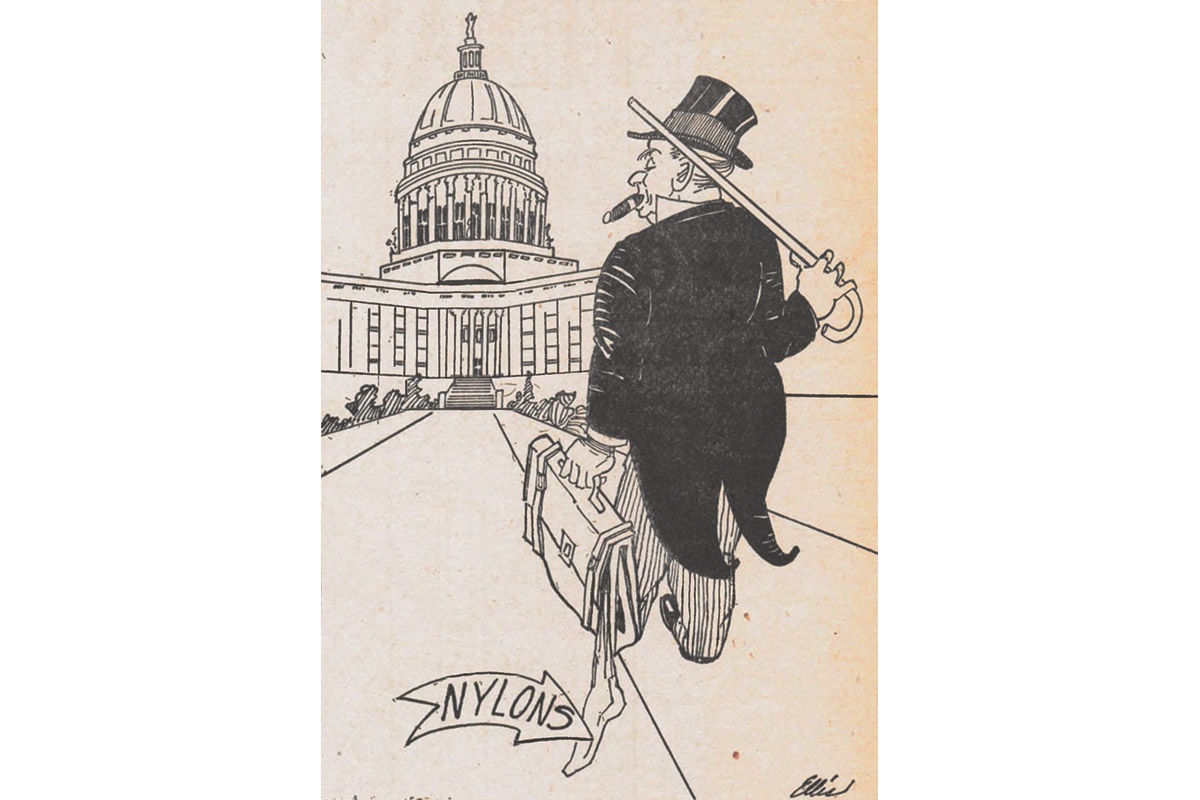

A nefarious figure strolled into Washington, D.C., toting a suspicious satchel filled to overflowing with contraband. In black top hat and tails, he swaggered toward the U.S. Capitol, a stogie clenched in his teeth. At least, that’s how a cartoon, titled A New March on Washington, portrayed him in the May 1946 issue of Texas Co-op Power.

And when this cad arrived in the Capitol, what happened?

He doled out nylon stockings to lawmakers’ wives.

The cad was Ham Moses, president of Arkansas Power and Light, an investor-owned utility. He offered the contraband to the wives of congressmen who would vote for an amendment—one prohibiting the Rural Electrification Administration from making loans to help generation and transmission cooperatives.

The scene was depicted as a cartoon, but it actually happened. Why was this payoff made of nylon? At the time, nylon stockings made a better bribe than a briefcase full of gold. In 1942, manufacturer DuPont had diverted its production to support the war effort. World War II robbed women of their cherished nylons, and the moment they began to sell again in 1946, stores were overwhelmed in nationwide riots. The payola was well-received, but the amendment failed.

“It’s almost unbelievable what the power companies will stoop to in their effort to kill us off,” responded Clyde Ellis, executive manager of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.

Long before this nylon campaign, the investor-owned utilities lobby already had thrown propaganda, bribery and legislative attacks at electric co-ops, with land grabs and lawsuits to come. Texas Co-op Power articles from 1951 to 1991 document attacks from investor-owned utilities, lobbyists, legislators and even journalists from The Wall Street Journal and The Associated Press. After realizing its mistake in refusing to electrify rural America in the 1930s, private power spent decades taking swings at the co-ops that met the challenge instead. The resulting David-and-Goliath scenario has played out repeatedly, making for strange stories.

Take, for example, the brief and brutal feud between U.S. Sen. W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel of Texas and George W. Haggard, the first editor of Texas Co-op Power and then manager of the statewide electric cooperative association.

O’Daniel was something of a Goliath, himself. Years of radio popularity, a stint as governor of Texas and six years in the Senate had accustomed him to saying whatever he wanted—and in 1947 he called the co-op system “communistic.”

Haggard fired back an indignant stone from his sling that flew to newspapers around the country via an Associated Press story: “This false and vicious charge …is a studied insult to the 160,000 patriotic, substantial tax-paying farm and ranch families of this state who receive electricity through the REA cooperatives.”

He attributed O’Daniel’s smear to three motives: “profound and abysmal ignorance” of the way co-ops operated; the tendency of O’Daniel’s congressional allies “to denounce everything that is for the general welfare of the American people as ‘communistic’ ”; and O’Daniel’s impending reelection bid.

Haggard then dealt the final blow, saying, “This looks like an effort to persuade the private utility interests, which hate the rural electrification program, to make a sizeable contribution to his campaign chest.”

And though O’Daniel would later level the communist charge at other targets, including many of his own Senate colleagues, Texas electric co-ops never heard from him again.

Ellen Stader, a former Texas Co-op Power communications specialist, is a writer in Austin.