Charles R. Townsend only quit talking about Bob Wills when his own life ended in 2023 in Canyon in the Panhandle. He was 93. As long as the retired American history professor at West Texas A&M University had breath, he taught, chronicled and celebrated Wills and his music.

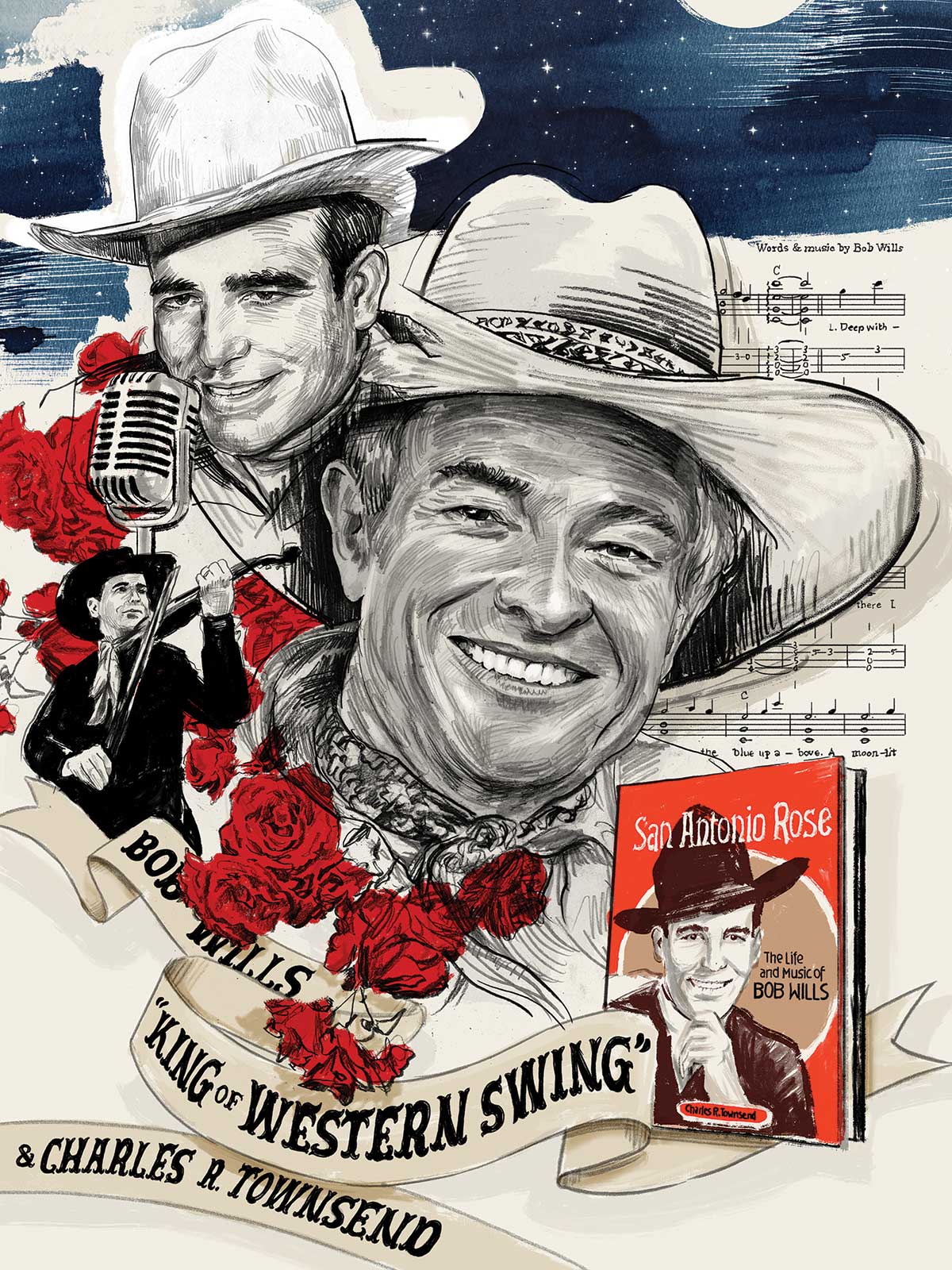

Townsend wrote the acclaimed 1976 biography San Antonio Rose: The Life and Music of Bob Wills and authored the liner notes for Wills’ final album, For the Last Time, for which Townsend won a Grammy in 1975. Both provided a road map to the life and career of an American original whose Western swing music, pioneered with his Texas Playboys, lit the world with its danceability for five decades. Wills was 70 when he died in 1975.

Townsend’s life had been interwoven with Wills’ since the mid-1960s, when he began studying and chronicling the musician, who began performing regularly in the late 1920s and formed his Texas Playboys in 1933. Townsend emceed the annual Bob Wills Day celebration in Turkey, Wills’ hometown, for 50 years, and at his last throwdown, in 2022, they renamed the outdoor stage in Townsend’s honor.

Wills, with his magnetic personality and high, lonesome holler, was as well-known as Coca-Cola in his heyday. New San Antonio Rose, one of his greatest hits, released in 1940, echoed through taverns around the world where U.S. servicemen sang along. One Texas boy said he thought it was the national anthem until he left the farm and joined the Army.

Yet a couple of decades later, and despite the Wills mania, Townsend learned the hard way about music pioneer biographies when he landed at West Texas A&M (then West Texas State) in 1967. He was told books about popular music history weren’t legitimate.

“I thought they were going to fire me when they learned I was going to write a book on Bob Wills,” Townsend said. “That was so far ahead of its time. The history department really looked down on that because it had never been done. And I was called in a time or two, but I had tenure, so I could write the book, and my gosh, look what it’s done.”

The publisher sold 10,000 copies of the book in six months in 1976.

“At the time it was published, it was the biggest selling book at the University of Illinois Press,” Townsend said. “I don’t say that bragging. It was Bob Wills who sold the book.”

Townsend believed that Wills chose him from among other writers for his eclectic musical tastes. “The reason he wanted me to write the book was that he knew he’d have someone to talk music with,” Townsend said. “It was the main topic of conversation, and if you tried to change the subject, he’d always come back to music.”

Once Wills gave him the go-ahead, Townsend and his wife, Mary, ranged from their home near Palo Duro Canyon State Park to Tulsa and Fort Worth to spend time with Bob and Betty Wills.

Invariably Bob Wills would be listening to music when Townsend walked in the door, maybe admiring Jerry Lee Lewis’ piano work or the vocally gracious Patsy Cline, who took a turn on both New San Antonio Rose and Faded Love.

As the biographer-biographee relationship grew, it evolved into mutual admiration. Wills, who already had suffered one stroke, was warned to expect a second, and that shifted Townsend’s thinking.

“I thought, well, one of these days he may have another stroke, and I’d like for him to know what he’s going to have in his book,” Townsend said. “When I got the book in manuscript, I had each chapter written out in longhand—I went over every chapter with him.

“I went all the way through the book, every chapter, and he listened intently and never said a word. When I got to the end, I said, ‘Bob, what do you think?’ He said, ‘It’s 100%.’ That’s a story that has never been published. I didn’t interview him too many times after that. He had his final stroke maybe a year afterward, when we were doing the sessions for Bob Wills’ For the Last Time.”

Those 1973 recording sessions featured Townsend introducing Wills and his Texas Playboys for the LP. The evening after the first day of recording, the album title proved fateful as the King of Western Swing had another stroke, at his Fort Worth residence, putting him in a coma.

“Before he died, he knew what was going to be in his biography,” Townsend said. “And I’m so glad he did.”