Texas history books tell of Sam Houston—military leader, frontier statesman, president of the Republic of Texas, governor of Texas—and point out that he owned slaves, 12 of them, and spoke in support of slavery to protect the interests of the South. But in principle he opposed the idea of one man owning another and even broke a law on its behalf. One slave in particular thrived under Houston’s tutelage and eventually earned his own place in Texas history.

When Sam Houston married his third wife, Margaret Moffette Lea, in 1840, she brought along two servants inherited from her father: Eliza, Margaret’s personal servant, and Joshua, a strapping lad believed to be 18. Already an expert horseman and experienced blacksmith when he arrived in Galveston with the newlyweds, he would serve them faithfully for more than 20 years.

Joshua’s quick mind made him an important member of the household, and he often traveled with Houston while he served as president of the Republic of Texas. Sam and Margaret taught Joshua and the other house servants to read and loaned them books, although teaching slaves to read was illegal in Texas, according to Patricia Smith Prather and Jane Clements Monday in From Slave to Statesman (University of North Texas Press, 1995). Joshua was so good with figures that Houston asked him to keep track of expenses as they traveled.

Joshua served the family as blacksmith, wheelwright, carpenter, driver and trusted companion. Houston once asked him to design and build a law office, separate from the rest of the house, at Houston’s Raven Hill Plantation on the upper San Jacinto River. Houston also encouraged Margaret to hire out the servants when they weren’t needed at home and to allow Joshua to keep the extra money he earned. Joshua’s skills made him a valued worker, especially as stagecoach driver. Sometime before 1848, Joshua began a family with a slave named Anneliza.

Rumors of war between the states circulated in 1859, and Joshua was aware of the general’s increasingly unpopular opposition to the spread of slavery. Houston’s pleas against secession fell on deaf ears, and Texas joined the Confederacy. Houston was removed from office in March 1861 after refusing to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederate States of America.

By 1862 the general’s health started to deteriorate. That fall, he set an example for fellow Texans once again. Dressed in his best suit and leaning on the hickory walking stick that Joshua had carved for him, he gathered his 12 servants and read Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation from the porch of his rented house in Huntsville. Then he told them that they were free. If they chose to stay and work for him, he promised to pay them as long as he could. Most, including Joshua, elected to stay.

On July 26, 1863, Sam Houston died. Joshua, who had taken his master’s last name, was away driving a stagecoach and by the time he returned, Margaret and her eight children had moved to Independence. The family was destitute and could not pay the rent on the Huntsville house.

Joshua made the 60-mile trip to Independence by mule to deliver his condolences. He brought $2,000—his life’s savings—and he explained that he wanted Margaret to have it. Overcome by emotion, she refused the offer. “I want you to take your money and do just what General Houston would want you to do with it if he were here, and that is to give your boys and girls a good education,” she is quoted as saying in From Slave to Statesman.

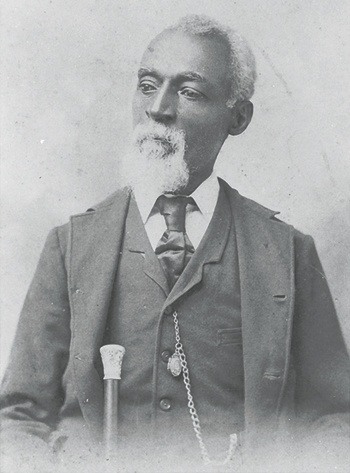

Thus began Joshua Houston’s long personal journey from slavery to leadership among freedmen, buying land in Huntsville and building a two-story house and a blacksmith shop. He served twice as city alderman and twice as Walker County commissioner. He was one of the founders of Bishop Ward Normal and Collegiate Institute in Huntsville.

Joshua Houston witnessed eight of the most turbulent decades in Texas history. Like his beloved master, he had a vision for his people, leading them beyond slavery to a new place in society. He died in 1902, probably at the age of 79, and is buried beside his third wife in Oakwood Cemetery in Huntsville, just a few yards from the grave of his friend, Sam Houston. Nearby stands an historical marker honoring the humble man born into slavery who became a civic leader and “a devoted supporter of education for African-Americans.”

——————–

Martha Deeringer, frequent contributor