I was four months and a day old when my grandfather, James A. Smith, better known as “Papa Smith,” died. I have no memory of him, of course, except in the stories that trace the lines of his considerable personality.

The story about how he restarted his family, finding a new bride (my grandmother, Bettie White Smith, or “Mama Smith”) after his first wife was tragically killed by a stranger’s stray bullet. Or the stories of how he could scold any of their 16 kids solely with the power of his voice and penetrating blue eyes. Or the story of how he constructed a small pine coffin for many a poor family who lost a child. But as much as anything, Papa Smith stories revolve around his dedication to the beloved four-part harmonies of Sacred Harp music.

Young singers help lead at the 2017 East Texas Convention in Henderson, which has convened for more than 150 years—making it the oldest Sacred Harp singing in Texas.

Photo courtesy Darrell Hancock

Like many Southerners who moved to East Texas a century or so ago, Papa Smith and his six brothers arrived with a copy of B.F. White’s seminal songbook, The Sacred Harp, from which the music takes its name. Next to the Bible, this oblong volume became one of the most common books in many rural homes of the time.

Photo courtesy Darrell Hancock

The Smith brothers had grown up singing Sacred Harp in Alabama and Georgia and wanted their families to carry on the tradition. In the 1910s the Smith brothers began hosting annual Sacred Harp singing and teaching sessions in their homes and nearby churches in northeast Texas.

Fa-Sol-La

The uniquely American form of religious folk singing known as Sacred Harp descended from 18th-century rural England, was adapted in New England and then took root in the rural South during the 19th century. The style is sometimes called “fa-sol-la” or “shaped-note” singing because its musical scale is notated using four shaped notes—triangle for “fa,” oval for “sol,” rectangle for “la” and diamond for “mi.”

Song leader at the 2017 East Texas Convention.

Photo courtesy Darrell Hancock

Unlike the modern “do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-do” scale, this earlier, four-note English system denotes the eight notes as “fa-sol-la-fa-sol-la-mi-fa,” the last “fa” being one octave above the first. Most modern four-part harmonies involve three lower singing parts supporting the melody of the highest singing part. But Sacred Harp features “dispersed harmony,” which means that each musical part—treble, alto, tenor and bass—contributes its own melody that freely flows in and out of the other parts to create a signature sound.

Song leader and Sacred Harp historian Robert L. Vaughn of Mount Enterprise at the 2017 East Texas Convention.

Photo courtesy Darrell Hancock

Some of Sacred Harp’s most powerful songs embody another early style called “fuging,” in which the four harmonized vocal parts, often paired, cascade in sequential order reminiscent of singing in rounds. Even on first hearing, one can recognize that Sacred Harp music stands apart from gospel or typical Christian church music. Its tonal blend creates a sweeping sound with a haunting, plaintive quality. The power of the sound is magnified by the words of the songs, often derived from ancient texts speaking of both great sorrow and even greater glory for the faithful.

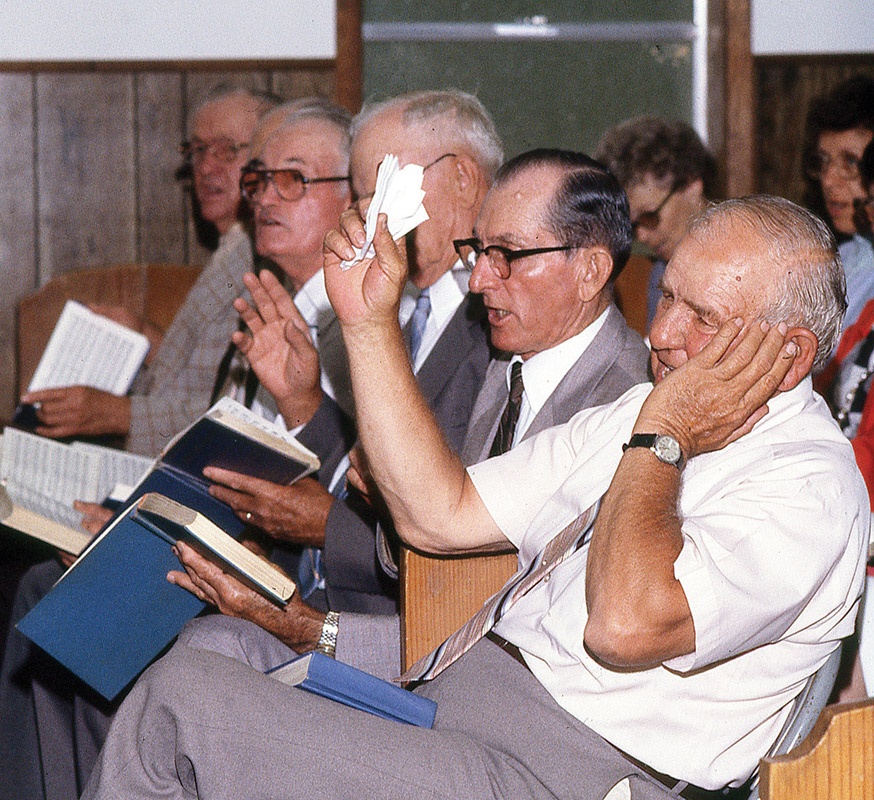

The 1986 Sacred Harp singing at New Prospect Church near Beckville in Panola County. Raised arms keep time with a song’s tempo.

Photo courtesy Randy Mallory

The physical positioning of singers during a session also sets Sacred Harp apart. Singers sit arranged by their four harmonic parts on each side of a “hollow square,” facing the song leader in the middle. Each singer may choose to take a turn as leader, typically for two songs. Holding the songbook in one hand and moving the other hand up and down with the rhythm, the leader motions to each part when it’s their turn to come in. Singing is strictly a cappella, so with no musical accompaniment, a designated “keyer” sounds the four parts for each song so everyone stays on pitch. Singers first “sing the notes” by voicing the shaped notes shown on the page, then they sing the words for one to three verses out of the songbook. All the while several singers may join the leader in moving their arms up and down in time. Others rock back and forth, caught up in the passionate harmonies. Many tap their feet discreetly, chiming in with robust “amens” at the end of each leader’s turn, especially if it’s a youngster.

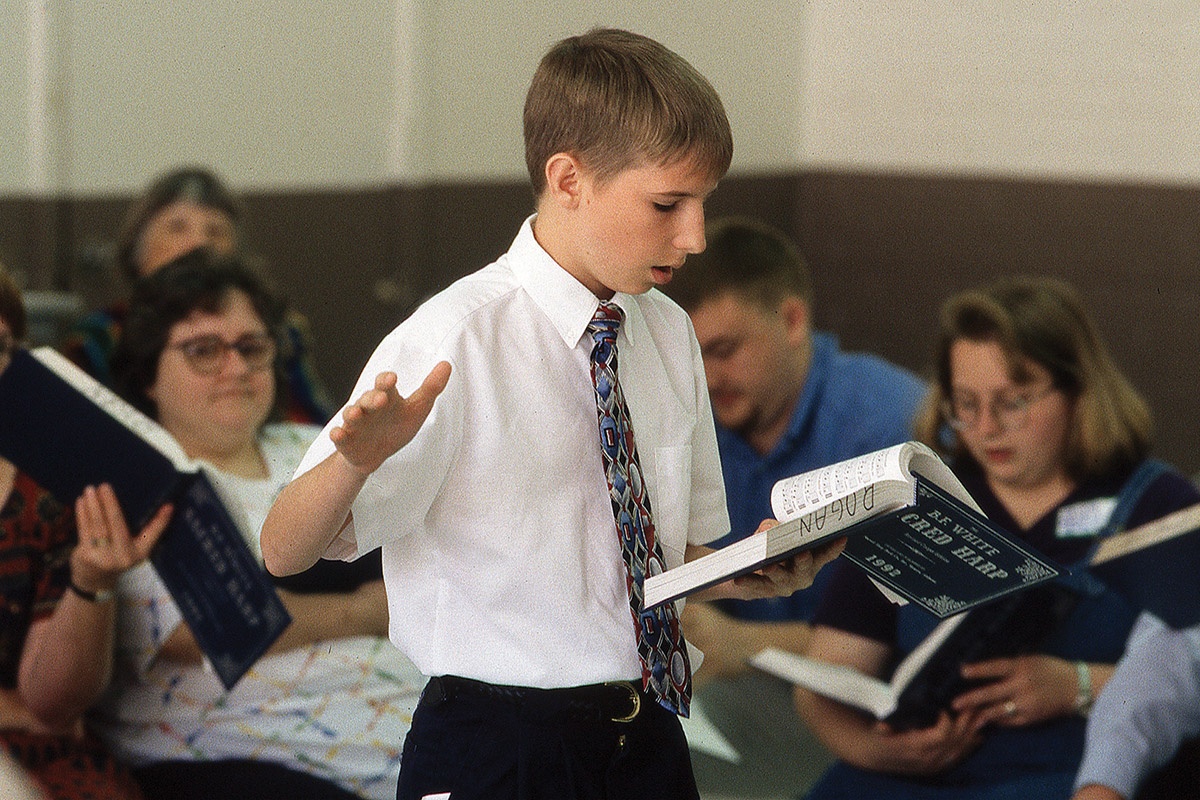

A youthful song leader carries on the singing tradition at the 2000 East Texas Convention in Henderson.

Photo courtesy Randy Mallory

That kind of fervent singing and leading has long been a hallmark of my singing Smith family, learned from one of Sacred Harp’s most famous teachers, Thomas J. Denson. The Alabamian traveled to Texas often to conduct singing schools in backwoods communities and cities during the 1930s and 1940s, a peak period for Sacred Harp music in Texas.

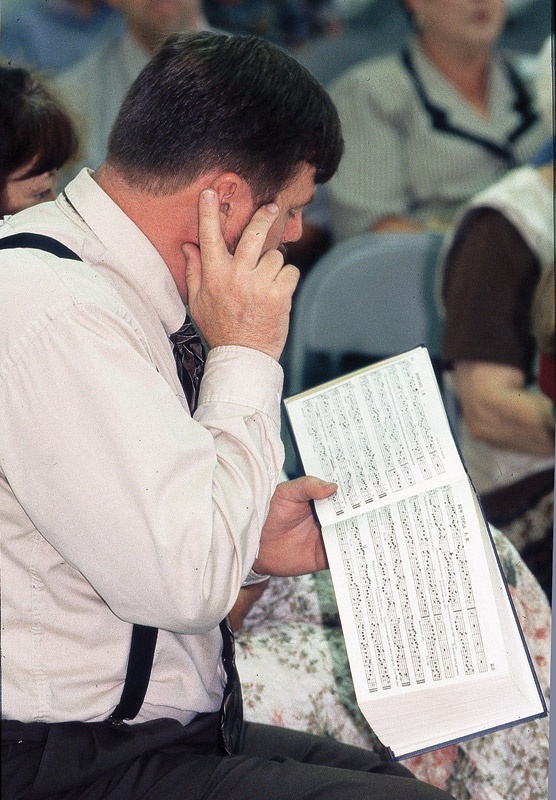

A singer focuses on his sound during the 2000 convention.

Photo courtesy Randy Mallory

Denson used a rolled-up cloth painted with clefs and scales as a portable blackboard. In the summer of 1934, the Smith brothers hosted a 20-day Tom Denson singing school at a Baptist church near Lindale, north of Tyler. Families came from across the area and dropped off 40–50 youths, leaving their care and feeding to the Smith clan.

Impassioned Sacred Harp singing at the 2000 East Texas Convention in Henderson.

Photo courtesy Randy Mallory

Students learned to sing and lead Sacred Harp all morning and for dinner enjoyed a home-cooked meal provided by the Smith brothers’ wives. When afternoon lessons concluded, the Smiths took their charges home with them to join in chores followed by rounds of splashing in nearby creeks. At night the youngsters slept on homemade quilt pallets scattered about the floor.

The author’s grandparents, Bettie and James A. Smith, welcomed many Sacred Harp singers and teachers to their Smith County home during regular Sacred Harp singing schools and conventions.

After intense practice at such lengthy schools, even young singers were ready to sing and possibly lead at major singing conventions. The Smiths regularly attended the Texas Interstate Sacred Harp Singing Convention held annually in August at the convention hall in Mineral Wells, west of Fort Worth. So many Smiths and their neighbors went to the 1934 event that young singers traveled the rough, slow roads seated on benches in the bed of a dump truck. One chaperone father stood in the back, chewing tobacco and spraying the congregants every time he spit. Noticing the unwelcome baptism, Papa Smith, who was driving, pulled over and instructed the man to use a soda bottle.

Sacred Tradition

My mother, nonagenarian Betty Smith Mallory of Tyler, is one of precious few Sacred Harp singers who recall the days of Tom Denson and summer singing conventions. After nearly 70 years singing as a family, the Smith brothers in 1980 expanded their annual singing into a communitywide event held in the Lindale area. The singing still welcomes singers each spring at the New Harmony community center near Tyler.

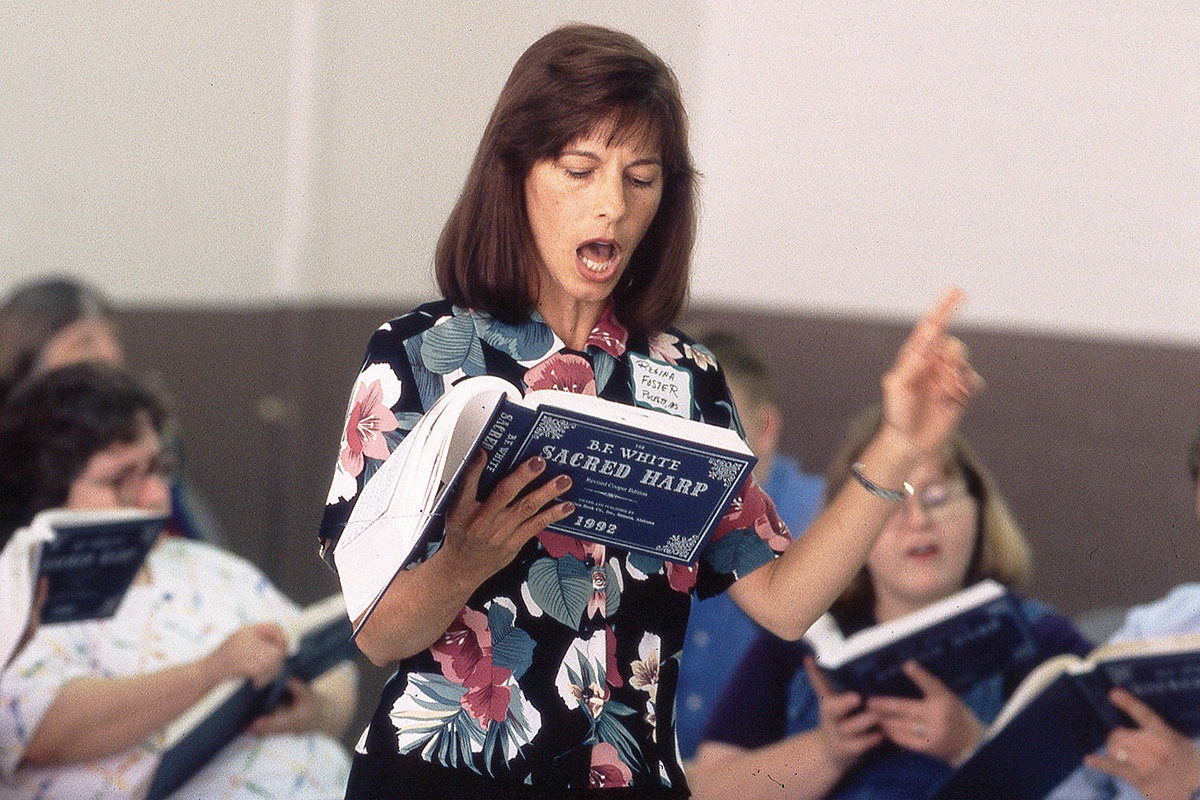

Myrl Smith Jones, a lifelong Sacred Harp singer and the author’s cousin, leads the 2000 convention.

Photo courtesy Randy Mallory

An even older singing gathering takes place each August in the civic center in Henderson. Organized in 1855, the East Texas Sacred Harp Singing Convention remains one of the state’s largest singing gatherings and the nation’s second oldest.

Sacred Harp music got a boost in 2003 when it was featured in the movie Cold Mountain, igniting renewed interest in the powerful musical form that has remained largely unchanged for nearly two centuries. Over the past few decades, in fact, Sacred Harp has grown across the U.S. and internationally, explains Robert Vaughn of Mount Enterprise, who attends and promotes singings across Texas.

A song leader at the convention in 2000.

Photo courtesy Randy Mallory

“It has grown in areas where the singings were not traditional and usually among people who find more interest in the folk aspect of the music than the religious aspect of the texts and tradition,” he said. “In Texas I would say that our base has decreased with the death of old singers and that we have not had enough growth to offset the loss. However, attendance at Texas singings has been good. Most of us travel a lot, and for our main conventions we have quite a few out-of-state visitors.”

Wondering about the future of Sacred Harp, I think of two truisms: “Nothing lasts forever,” but also “hope springs eternal.” So, on behalf of the grandfather I never knew, here’s to hoping that a new generation of singers will get hooked on these rich and rare harmonies. As Uncle Tom Denson warned at the start of each Sacred Harp singing school, “If some of you don’t like this music, all I’ve got to say to you is you’d better get out. If you stay here, it’s going to get hold of you and you can’t get away.”