For decades, a huge swath of potassium-rich soil just west of Pecos produced what many Texans swore were the sweetest and best cantaloupes in the world. But over the past few years, the number of Pecos cantaloupes available in Texas grocery stores has declined drastically, and there have been rumors that those for sale are not really from Pecos at all, but from the nearby town of Coyanosa.

This spring, I went to Pecos to see what made the melons so good, where they are really from, and what has caused annual plantings to plummet from a peak of roughly 1,800 acres in the early 1990s to about 100 acres today. I talked to a dozen active and retired cantaloupe farmers and agricultural extension specialists, and I learned that the traditional Pecos cantaloupe has a small seed cavity and a corresponding abundance of orange flesh. The flesh’s peculiar sweetness is created by a combination of the potassium in the soil in which the cantaloupes are grown and the long hours of dry sunshine that nourishes them, abetted by the magnesium and calcium salts in the water with which they are irrigated.

Roland Roberts, a retired High Plains vegetable specialist for the Texas Agricultural Extension Service, says potassium favors the accumulation of sugars in the melons, and the salinity of the water prevents them from absorbing too much moisture, which would blunt the sweetness.

As veteran Pecos cantaloupe grower Roger Jones says, “The saltier the water, the sweeter the melon.” Jones, who planted 100 acres of cantaloupes this year, said he is the last person in Pecos growing cantaloupes commercially, the last link in a tradition that is nearly a century old. The 69-year-old Jones moved to Pecos from Mercedes in 1979 and says he is “the oldest continual farmer in Pecos.”

Over the years, he has grown cotton, onions, cabbage and honeydew melons and even harvested four-wing saltbush seed from a plant that provides erosion control. Jones says, however, he never could have made a living farming without teaching auto mechanics at Pecos High School for the past 30 years, a job he still holds. He’s selling this summer’s cantaloupe crop to chain stores statewide, including Wal-Mart, H-E-B and individual distributors. But most Pecos cantaloupes, Jones confirms, don’t come from Pecos: They’re grown near Coyanosa, about 30 miles southeast of Pecos.

Chillin’ on the Train

The railroad first made Pecos cantaloupes famous. Madison Lafayette Todd, better known as M.L. Todd, came to Pecos from New Mexico in 1916 and bought an interest in an irrigated farm, where he and a partner, D.T. McKee, planted cantaloupes with seed from Rocky Ford, Colorado. They contracted with the dining-car service of the Texas and Pacific Railroad, which ran through Pecos, to buy their crop. The T&P listed the cantaloupes as “Pecos cantaloupes” on its breakfast menus, and dining-car stewards provided satisfied diners with chilled cantaloupes and Todd’s address. By the 1920s, Todd was shipping cases of Pecos cantaloupes all over the country by Railway Express.

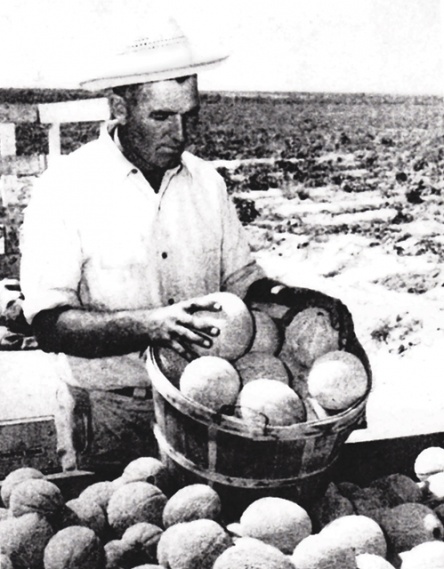

Ray Thompson, Todd’s grandson, remembers that in those days, the train stopped in Pecos for just 20 minutes. During the shipping season, there was always a mad rush from the packing shed to the railroad station, with every available hand climbing on trucks already loaded with wooden cases of cantaloupes to get them into the express car before the train pulled out. Some customers ordered a case a week through summer. By the late 1940s, Todd had 240 acres planted in cantaloupes and was shipping 40,000 crates a year to customers in 42 states. Meanwhile, other growers had appeared on the scene.

Expensive To Grow

Cantaloupes, which are picked by hand and processed by hand in the packing shed, are a labor-intensive crop. The melon pickers and packers in Pecos were migrant workers, many from Mexico. Hope Wilson, who with her husband grew cotton as well as cantaloupes in Pecos in the 1950s, said at the height of the picking season, they had 1,500 migrant workers on their payroll.

Sally Williams Perry, whose father, Jack Williams, raised “Famous Pecos Cantaloupes,” recalled that on Saturdays in the ’50s, Pecos was teeming with people, including migrant workers who had come into town to shop before heading back to farms.

By the 1970s, there were five companies growing cantaloupes in Pecos, each with its own packing shed, and they shipped their melons by truck instead of train. The largest grower was the Pecos Cantaloupe Company, owned by A.B. Foster, who had first come to Pecos as an accountant for Billy Sol Estes’ cotton farming and fertilizer business. In 1990, Foster had 1,000 acres planted in cantaloupes and raised 10 different varieties, each of which ripened at a different time of summer. “But varieties had nothing to do with the taste,” said Randy Taylor, who bought the company. “The flavor was in the soil.”

All of the packers marked each cantaloupe with stickers denoting them as from Pecos.

No Way To Make a Profit

In the mid-’90s, however, the Pecos cantaloupe industry began to fall apart. The problems started as early as 1964 when the federal government ended the bracero program: an agreement originally made between the U.S. and Mexican governments in 1942 to bring contract workers from across the border into the U.S. to meet labor shortages created by World War II.

Migrant workers from the Lower Rio Grande Valley replaced the braceros, but their wages were higher than the 60 cents an hour paid to the braceros, and the migrant workers’ pay continued to rise through the 1970s and ’80s. Then, on top of those higher labor costs, farmers saw the water table start to fall and the price of natural gas begin to rise.

In the late 1950s, natural gas was piped to Pecos, fueling farmers’ water pumps. But the price of natural gas rose from 8 cents per 1,000 cubic feet to 30 cents. By 1989, it was 70 cents, and by 2006, when most of the growers had given up, it was $7 per 1,000 cubic feet.

Hybrid seed cost also escalated. Field Yow, Foster’s son-in-law, remembered that in 1977, seed cost about $6 per acre; by the time he got out of the business in 1997, it cost about $100 per acre. Wilson said she and her husband quit growing cantaloupes when they realized that each crate they sold for $18 was costing them $35 to produce.

By 1995, it was clear there was no way to make a profit growing cantaloupes in Pecos. The expenses were just too high.

Moving to Coyanosa

That’s when the Pecos cantaloupe industry moved to Coyanosa. The four Mandujano brothers, Tony, Armando, Junior and Beto, had actually started growing cantaloupes there in 1982. Tony Mandujano said that the first year, they planted half an acre. But that half-acre happened to be part of a patch of potassium-rich soil almost identical in composition to what it is in Pecos. In 1997, they incorporated as Mandujano Brothers Produce, a diversified farming company that now has 6,000 acres of watermelons, onions, cotton, hay, peppers, pumpkins and cantaloupes. They use migrant labor obtained through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s H-2A program, which allows nonimmigrant foreign workers into the country on visas to perform agricultural work for employers who anticipate a shortage of domestic labor.

The Mandujano brothers keep costs down with mechanization. They use a tractor-pulled vacuum-air planter—which plants one seed in each hole drilled—and a conveyor belt that carries melons from the field to the truck, although human hands still put the cantaloupes on the belt.

The brothers have also cut out middle management. “We are four brothers,” Tony Mandujano said. “And we are our own managers.” This year, the brothers planted 300 acres in cantaloupes, about 90 percent of which now, this summer, is being sold in Texas to grocery stores statewide such as Fiesta Foods, H-E-B, Kroger and Wal-Mart, and to roadside vendors.

Because Coyanosa is in Pecos County (Pecos itself is in Reeves County), each melon receives a sticker bearing a map of Texas crowned with a Stetson hat and the all-important label: “Pecos Fresh.” The shipping process can last two to three months, Tony Mandujano says, but once the cantaloupes are in stores, you’d better act fast: Their shelf life is seven to 10 days.

But that’s not the end of the story. The Mandujano brothers’ biggest competitors are in California, where 40,000 acres were planted in cantaloupes in 2010. “California cantaloupes are half the price of our cantaloupes,” Tony Mandujano said, “but they are only half as good. People who buy them are confused.”

But they may represent the future. Juan Anciso, a Texas AgriLife Extension Service vegetable specialist for the Rio Grande Valley and a cantaloupe expert, said most of the cantaloupes in Texas grocery stores from June to December come from California and Arizona; from January to May, they come from Honduras and Guatemala. So if you want Texas cantaloupes (they’re typically available in July and August), look for that Pecos label, even if the cantaloupe it’s on isn’t exactly from Pecos.

——————–

Writer and historian Lonn Taylor lives in Fort Davis.