In Fredericksburg in 1847, a young German immigrant leader and a powerful Comanche chief signed a mutual defense pact believed to be the only unbroken peace treaty between American Indians and U.S. settlers.

The German immigrant society had purchased the 3.88 million-acre Fisher-Miller grant, which had to be surveyed by fall 1847 or it would be forfeited. What the immigrants did not know was that the Comanche, the most feared of tribes, claimed that area as their hunting grounds. Making peace with the Comanche became the responsibility of John O. Meusebach, the 33-year-old commissioner-general of the immigrant group.

In late January 1847, Meusebach rode north from Fredericksburg into the land grant with a small survey party. Meeting with Chief Ketemoczy of the Penetaka Comanche and other chiefs in an initial parley, Meusebach explained his friendly intentions, saying he represented towns that would welcome them. In return, he expected hospitality from his Comanche neighbors.

Ketemoczy dubbed the red-haired Meusebach “El Sol Colorado” (Red Sun) and promised to summon the chiefs of the western bands of Comanche to a peace council on the San Saba River at the next full moon.

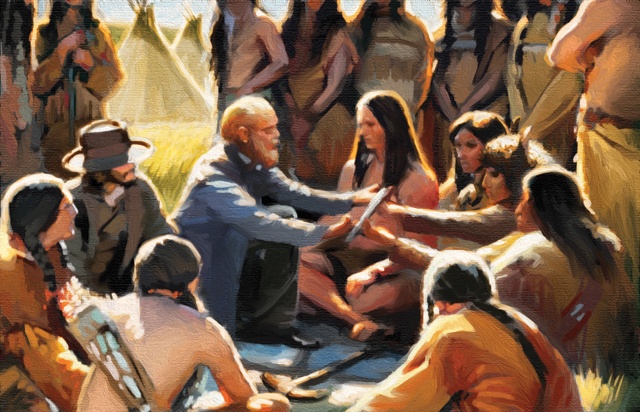

Meusebach and his party explored parts of the grant and arrived on March 1 approximately 10 miles southwest of today’s city of San Saba to participate in the peace council. They were greeted by the scene of several hundred Comanche warriors standing behind the head chiefs: Buffalo Hump, Santa Anna and Old Owl. El Sol Colorado sat with them on buffalo robes, as the chiefs and he negotiated the terms of the treaty. On March 2, the talks concluded with a peace pipe and an agreement.

The treaty allowed the colonists to travel freely between the Llano and San Saba rivers. Likewise, the Comanche could come into the settlers’ towns without fear. The Comanche promised to tell the colonists if hostile tribes were near the settlement, and the Germans vowed to assist the Comanches against their enemies. For allowing surveyors and colonists onto the land, the Comanches would receive $3,000 in provisions and presents, according to Irene Marschall King, author of “John O. Meusebach: German Colonizer in Texas.”

On May 9, 1847, the treaty between the German Immigration Company and the Comanche nation was signed in Fredericksburg by six Comanche chiefs, Meusebach and seven others. After feasting and collecting their provisions and presents, the Comanche went home.

The treaty between the immigrants and the Comanche was unique: The government had no part in it. Despite a few infringements, the agreement held. The immigrants’ farms around Fredericksburg were safe from Comanche raids. The Comanche kept their hunting grounds, while tribes elsewhere were being forced onto reservations.

Meusebach went on to serve in the Texas Senate and marry a German countess. He died on his Loyal Valley farm north of Fredericksburg in 1897.

But the story doesn’t end there.

Comanches were known for using smoke signals over long distances (a historical marker designates a signaling ground near San Saba). Legend says that during the March negotiations (which had taken place about 70 miles north of Fredericksburg), Comanche signal fires on the hills above Fredericksburg alarmed some children. Blending the Old World German tradition of Easter eve hill fires and Easter Rabbit tales, a Fredericksburg mother reportedly calmed her children by telling them that the signal fires were bunnies boiling Easter eggs.

But Easter in 1847 fell on April 4, not in early March. Over time, that merging of fact and legend was manifest in the Fredericksburg Easter Fires Pageant held for many years at the Gillespie County Fairgrounds the evening before Easter. The event, said Evelyn Weinheimer of the Pioneer Museum in Fredericksburg, celebrated a treaty unbroken and the peoples who agreed to live together peacefully.

———————-

Eileen Mattei, a member of Nueces EC and Magic Valley EC, lives in Harlingen.