For a woman who was once on the run from a drug cartel, Sue Machetta seems surprisingly relaxed in Mexico. I don’t mean the chaise-longue, umbrella-drink kind of relaxed. I’m talking about the composure that appears when you’re certain you’ve found your calling. Even though they live in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, Sue and her husband, Jerry, work with the Mexican Children’s Refuge, a nonprofit that provides scholarships for children across the border, in Nuevo Progreso, Mexico.

After spending one day with the couple in Mexico, I had a hard time keeping up with all the ways they’ve found to improve the lives of the impoverished. Each year, this couple and thousands of Winter Texans like them spend an enormous amount of their time and resources to give back to the community that’s taken them in.

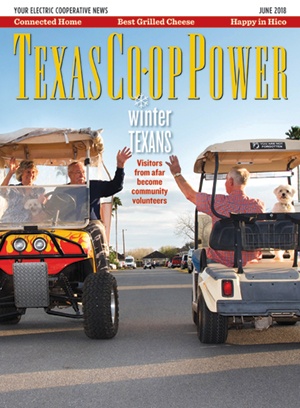

Winter Texans spend a few weeks to a few months in the Lone Star State each year, usually to escape harsh winters in the northern U.S. About half own or rent a mobile home in the Rio Grande Valley; another third own a recreational vehicle; and some own a second home or condo.

According to a 2016 study conducted by the Business and Tourism Research Center at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, approximately 96,000 Winter Texans visited the area in 2016. That seems like a lot, but that number is down from 144,000 in 2010. Kristi Collier of Welcome Home RGV, an organization that provides resources and support for Winter Texans, says the decline isn’t surprising.

“The No. 1 reason people come down here is word of mouth,” Collier says. “They heard about it from a friend who was coming here. There were times when you couldn’t find an RV spot because they were all full. But every year, due to attrition, we lose people. Some are in poor health. Some pass away. We’re kind of in that transitional phase where [we] haven’t been replacing them as fast as we’ve been losing them.”

When pressed for a ballpark figure, Collier estimates that today the mobile home parks are about 75 percent full. She says back in the 1980s, the region did quite a bit of marketing in the Midwest, which is where the great majority of Winter Texans hail from. But once the parks got full, marketing efforts dwindled.

Despite their waning numbers, Winter Texans’ economic impact is staggering. According to the aforementioned study, Winter Texans funneled an estimated $760 million into the Rio Grande Valley economy in the 2015–2016 season and injected another $30.6 million into Mexican border towns. But the value of volunteerism that Winter Texans bring might be an even greater benefit than the money they spend.

The Machettas, who heard about the Rio Grande Valley from friends, unwittingly sold their beekeeping business and home in South Dakota to a person involved in drug trafficking. While the authorities sorted out the details of the case, the Machettas drove their RV to Texas to keep a low profile as the case was resolved. They visited Nuevo Progreso and met a shoeshine boy who ignited their passion to serve that community. That was eight years ago.

Eventually they joined forces with Dr. Eva Lilia Garcia de González, a physician in Nuevo Progreso who is the Mexican director of the Mabel Foundation, a nonprofit that provides medical care, food and scholarships to the community. (Mabel Clare Proudley was a Weslaco-based humanitarian and philanthropist who devoted most of her life to serving the people in and around Nuevo Progreso.) The Machettas live in the RGV for four months each winter, but their work on behalf of the poor in Nuevo Progreso is year-round.

“When we were young, our grandparents often just sat in rockers watching the world go by,” Sue Machetta says. “People were there to help us when we were struggling and trying to raise our families and pay tuition fees, and now it’s our turn to pay it forward!”

They make furniture and intricate woodcarvings, sew quilts, and paint on canvas and glass, and they sell the items to fund their work with the refuge. Sue Machetta recently had the idea to found a trade school for those who don’t have access to traditional education. Plans are in the works for sewing, woodworking and welding courses, with other trades and music classes forthcoming. The Machettas are just two Winter Texans who devote themselves to charitable causes in and around the Rio Grande Valley.

It’s a cold, drizzly January day in South Texas when I pull into Trophy Gardens RV Resort in Alamo. I selected this community, a member of Magic Valley Electric Cooperative, out of The Park Book, a guide that lists 330 RV and mobile home parks in the Rio Grande Valley.

I’m here to see if I can gain a better perspective on how Winter Texans spend their time. As I walk through the main entrance, I notice a group of people playing shuffleboard. The weekly calendar of events on the wall makes me tired just to read it. I note several art and sewing classes, including a crocheting and knitting group that calls itself “The Happy Hookers.” The calendar includes a profusion of card games, sports and exercise opportunities. Every Saturday night, the park hosts a dance with a live band. Clearly, these people aren’t skimping on the fun of being retired. But somehow they still manage to find plenty of time to give back to their seasonal community.

“We go to police stations and schools to ask what areas, what children need help,” says Janet Yeley, who serves on the board of the park’s nonprofit organization, Caring for Others. “There’s a new shelter going in for women and children, so we’re going to try and see what their needs are. Every Tuesday morning, we meet to consider where to concentrate our efforts.” Trophy Gardens residents founded CFO more than three decades ago. Their aim is to design creative ways to help needy children and families.

Their efforts are eclectic and inspiring.

Some residents help care for premature babies at an area hospital. Others play Santa or take food and presents to the poor on Christmas Eve. One man collects old bicycles, refurbishes them and gives them to people who need transportation. Another man collects used carpet, cleans it and makes beds for children in Mexico. A women’s group collaborates with the Rio Grande Valley Quilt Guild to make quilts for individuals in the U.S. military.

“We have residents that drive the van to the Shriners hospital in Houston,” says Lynn Murray, who with her husband, J.D., manages Trophy Gardens. “They pick the kids and a parent up at the border, drive them to Houston and then spend the night with them at a hotel.”

Everything the Trophy Gardens RV Park donates is either made by residents or purchased with funds raised by park residents. They have bake sales and make things like hats and blankets. They organize food drives. One of the most popular fundraising efforts is the park’s donation station, where residents contribute clothing and household items.

“Every Wednesday they bring us their donations,” says Yeley. “I get it all ready, fix it up, make sure any appliances work. Then they all come back on Tuesday and give money for what their neighbors have donated. All proceeds are used to fund our work in the Alamo community.”

Most Winter Texans I met convince me that they’re a resourceful bunch. Many referenced Collier’s organization as a heartwarming presence and a phenomenal resource. But her company exists to serve the needs of Winter Texans, not to spearhead their volunteer efforts. I never encountered anyone who was organizing volunteers on a large scale. Winter Texans effect positive change in a multitude of singular ways.

“I think volunteerism is part of the Midwest values,” says Murray. “A lot of our residents come from Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, even Canada. I think they’re taught from a young age to give back to the community. So that continues no matter where they are.”

Murray and her husband live in the Valley full time, and she says one thing she really appreciates about her adopted state is the inclusion implied by the name part-time residents are widely known by.

“The great thing about coming to Texas is the term ‘Winter Texan,’ ” Murray says. “You’re not just a snowbird here. You’re considered a Texan.”

Laura Jenkins is a writer and photojournalist based in Austin.