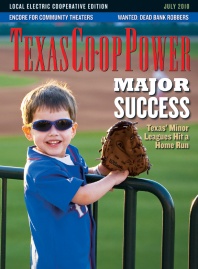

Hunter Nicodemus, 10, and his brother, 6-year-old Haley, are standing on the left-field berm, a towel draped over Hunter’s shoulder. The boys are waving at a group of players who are shagging fly balls during batting practice. “Please, please, throw one up here,” says Haley. His brother shouts at another player.

The boys look up—a couple of baseballs are headed their way. Their father, Gene, is watching from the walkway in back of the berm. “What do you say?” he asks. The boys shout their thank-yous, several times, and run off toward their dad, clutching their souvenirs. Their next stop? The swimming pool on the other side of the right-field fence at Frisco’s Dr Pepper Ballpark. It’s just another night for minor-league baseball in Texas.

Forget everything you thought you knew about the minors—the bush-league towns, the broken-down stadiums, a few fans scattered around the stands. Minor-league baseball is far from minor league in Texas, which is helping spark a decadelong resurgence at this level of play throughout the United States. A total of 17 teams in five leagues—including five teams that are officially associated with the Minor League Baseball organization—stretch across the state, from the Rio Grande Valley, to far West Texas, to the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex and the Panhandle. These days, the ballparks are just as likely to have a wine bar as a hot-dog stand, and swimming pools and rock-climbing walls are common. In fact, the action is not so much about the game on the field as it is luring families away from the local multiplex.

“More and more, minor-league operations are sophisticated businesses,” says Scott Sonju, president and general manager of the Frisco RoughRiders, a Texas Rangers Double-A farm team. The RoughRiders are owned by the Mandalay Entertainment Group, a Hollywood media conglomerate that owns five other minor-league teams, including two New York Yankees affiliates. “They’re sophisticated about customer service, about marketing and operations,” Sonju said. “It’s not as much about the win-loss record as it is the fan experience.”

Back in the game

This is not the way things used to be. For more than 100 years, the minors, including independent leagues, were where baseball players who weren’t good enough or who weren’t yet ready for the major leagues played. And after World War II, fewer and fewer people noticed. By the 1980s, the minors were in disrepair, and it wasn’t unusual for a team to appear one season and vanish the next. Want to buy a team? Promise to pay off its debts, and the team was yours. Not that anyone wanted one.

But four things happened over the next decade to change that. First, major-league baseball, which would have lost its player-development system if the minors failed, reached an agreement with the minor leagues to upgrade stadiums and operations. Second, the old-timers retired or died and were replaced by modern operators like Sonju; Jay Miller, the chief operating officer and president for the Triple-A Round Rock Express; and John Dittrich, former president of the independent Fort Worth Cats who retired after the 2009 season. These men, says David Broughton, research director for the Sports Business Journal, are businessmen as much as baseball fans. It’s not just about making money—it’s about making enough money to plow it back into the business to maintain sophisticated operations. The RoughRiders have 42 full-time employees and more than 100 part-time employees during the season, so it’s all but impossible to walk around the ballpark without someone asking if you need help.

Third, the 1988 movie “Bull Durham,” starring Kevin Costner, brought romance and mystique to the minors and introduced it to a new, hipper generation of baseball fans. Fourth, and perhaps most important, cities large and small discovered the value of a minor-league team as a tourist draw and a way to market their communities to attract new businesses and residents.

“We want to be part of the global sports community, and this is one part of what we do,” says Frisco Mayor Maher Maso, whose city paid $22 million to help build its 8,800-seat ballpark. Frisco is also home to a professional soccer team, FC Dallas, which plays at the 20,000-seat Pizza Hut Park, and a minor-league hockey team, the Texas Tornado, which plays at Dr Pepper Arena. The city also plays host to a variety of regional and national competitions for gymnastics and figure skating.

“It’s all about the economic impact,” says Maso, whose community opened three hotels last year in the bottom of the recession. “It’s not just the jobs they create, but it’s the people they draw.”

Some teams major-League affiliates, others independent

Texas’ 17 teams consist of two groups. As official members of Minor League Baseball, five teams develop players for Major League Baseball: Round Rock, which plays in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League; and Corpus Christi, Frisco, Midland and San Antonio, which play in the Double-A Texas League. The remaining 12 play in three independent leagues: El Paso, Fort Worth and Grand Prairie in the American Association of the Independent Professional Baseball; Amarillo, Coastal Bend (Robstown), Edinburg, Laredo, Rio Grande Valley (Harlingen) and San Angelo in the United League; and Alpine and two teams currently based in El Paso, the Desert Valley Mountain Lions and the Coastal Kingfish, in the revamped Continental Baseball League.

Affiliation is the main difference; the major-league teams pay the players in the affiliated leagues, while the independent teams foot the salaries themselves. Otherwise, the approach is much the same.

“We’re an alternative at an affordable cost,” Dittrich said while he was still president of the Fort Worth Cats. “That’s why it works in places like Fort Worth and the suburbs, where people never thought it would work. You can go to one of our games and be home in time to watch the 10 p.m. news, and you don’t have to pay major-league prices.”

Dittrich has a point. There are three independent-league teams in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, each theoretically competing with the major-league Texas Rangers. But there’s nothing minor about the bargains: You can buy a hot dog, soda and chips at a RoughRiders game for $7—a jumbo hot dog alone at a Rangers game costs $4.50. And a seven-game RoughRiders ticket package is $63, or $9 per game, while a mid-price-range, single-game ticket for a Rangers game typically costs between $25 and $30.

“There’s an abundance of entertainment options, and they keep growing,” says Sonju. “You can go out to a restaurant for dinner or you can participate in youth sports. So we have to find a way to get you to come to our ballpark.”

Hence the proliferation of mascots like the RoughRiders’ Deuce the prairie dog (and his cousin Daisy) and the park’s nonbaseball activities like the swimming pool, playground and wine bar. At Round Rock’s Dell Diamond, you can sit in a rocking chair beyond the left-field fence. And there are more promotions and special events than seem possible, from birthday parties and between-innings giveaways to Scout night and old-timers games.

It’s no surprise then that minor-league attendance is skyrocketing. The minors set an attendance record in 2008, though slumping slightly last year during the recession. In Texas, top teams like Frisco and Round Rock have mostly set records each year of their existence.

“The kids get more out of this than they do if it’s a major-league game,” says Gene Nicodemus, watching his sons run for the swimming pool. “It’s more personal. When you got a big stadium, it’s overwhelming. And you can’t beat the price.”

Or the swimming, either.

——————–

Jeff Siegel has written about chili and chicken-fried steak for Texas Co-op Power.