Just 45 miles west of Houston, thousands of cars and trucks zoom along Interstate 10 every day paying little attention to the exit for FM 1458. If those drivers took that exit and headed north a mere two miles, they could travel back in time two centuries.

With a little imagination, visitors can relive the fascinating, tragic and consequential story of San Felipe de Austin, capital of the first American colony in Texas. While not as well known as other early Texas historic sites—Washington-on-the-Brazos, the Alamo and San Jacinto battlefield—the colony played a pivotal role in how and why Texas began.

This is where empresario—land contractor—Stephen F. Austin became the “Father of Texas.” Austin was able to attract 300 families, still remembered as the Old 300, to colonize the area in the mid-1820s. San Felipe de Austin is where the immigrant Texians built farms and towns under Mexican law, until changing rules riled them to revolt.

“This is where Spanish Texas became the Republic of Texas within 15 years,” said Bryan McAuley, manager of the San Felipe de Austin State Historic Site. “I like to tell folks I can connect almost all of the Mexican Texas era’s prominent people and places to the town of San Felipe de Austin. This is a great place to begin or expand your love of Texas history.”

With state-of-the-art facilities recently completed, there’s never been a better time to take that I-10 exit and learn about the birth of Texas.

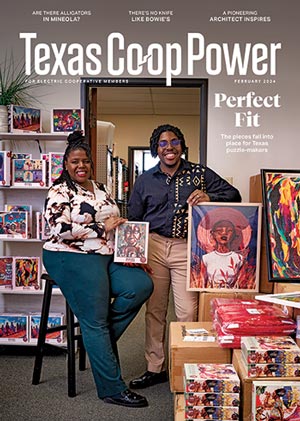

Interactive murals let visitors explore the capital of Texas’ first Anglo town.

Courtesy of The Texas Historical Commission

Opened in 2018, the visitor center features in-depth and interactive exhibits and murals as well as a partially preserved log cabin and 1830s-style printing press.

Courtesy of The Texas Historical Commission

Remembering San Felipe

Locals have long honored San Felipe’s history. Nearly a century ago, they began setting aside land as a park, later adding an obelisk and a statue of Austin that still rises above the original townsite. Locals also hold an annual Father of Texas celebration honoring Austin.

The first formal archaeological work started in the 1990s. The site became part of the Texas Historical Commission in 2008 and underwent further archaeological study. In 2018, the THC opened a 10,000-square-foot museum—built using state and private funds—located on 100 acres of the townsite.

As you stroll through the modern museum, you pass well-crafted interpretive exhibits, interactive high-tech displays, wall-sized murals and an 1830s cabin with period artifacts. A two-part video documentary follows the growth of San Felipe into Mexican Texas’ second largest town, after San Antonio, and its dramatic demise. In 2021, the THC added an outdoor exhibit called Villa de Austin where replica structures recreate the old town.

Together the museum and villa capture the ebb and flow of frontier life, business and politics.

The Early Days of San Felipe

Central to the story is Austin himself, who first laid eyes on southeast Texas in 1821. “The country is as good in every respect as man could wish for,” he reported

“Land, all first rate, plenty of timber, fine water—beautifully rolling.”

Austin took over as empresario when his father, Moses Austin, died in June 1821. The original colonial contract with Spain had to be renegotiated because Mexico had just gained independence from Spain.

Officially founded in 1823, the colony covered 4 million acres—bordered east to west by the San Jacinto and Lavaca rivers and south to north by the Gulf of Mexico and El Camino Real, the King’s Highway to the national capital of Mexico City. Stephen F. Austin would eventually settle some 1,500 American families—mostly Southern agriculturalists—in his colony and its capital of San Felipe de Austin.

Initially Austin saw himself as a loyal Mexican citizen, as required by his contract. He learned Spanish, went by Estevan (Stephen in Spanish) and became well acquainted with key Mexican officials.

“If you had a problem as an American in Mexican Texas, he was your go-to guy,” said Jordan Anderson, site assistant manager.

Austin was a patient, prudent leader who tried to make the system work. Immigrant families abided because they had something to lose, explained Anderson. During the 1820s and ’30s, they converted wilderness into productive farms and businesses.

“Later arrivals began bucking Mexican rule and even criticized Austin as too Mexican,” Anderson said. “But he was able to find workarounds to soften the impact of changing Mexican laws, especially ones that limited immigration and made slavery illegal.” (Many immigrant American families arrived with enslaved workers who eventually accounted for a quarter of the colony’s population.)

Special events often feature reenactors portraying characters from the early Stephen F. Austin colony.

Courtesy of The Texas Historical Commission

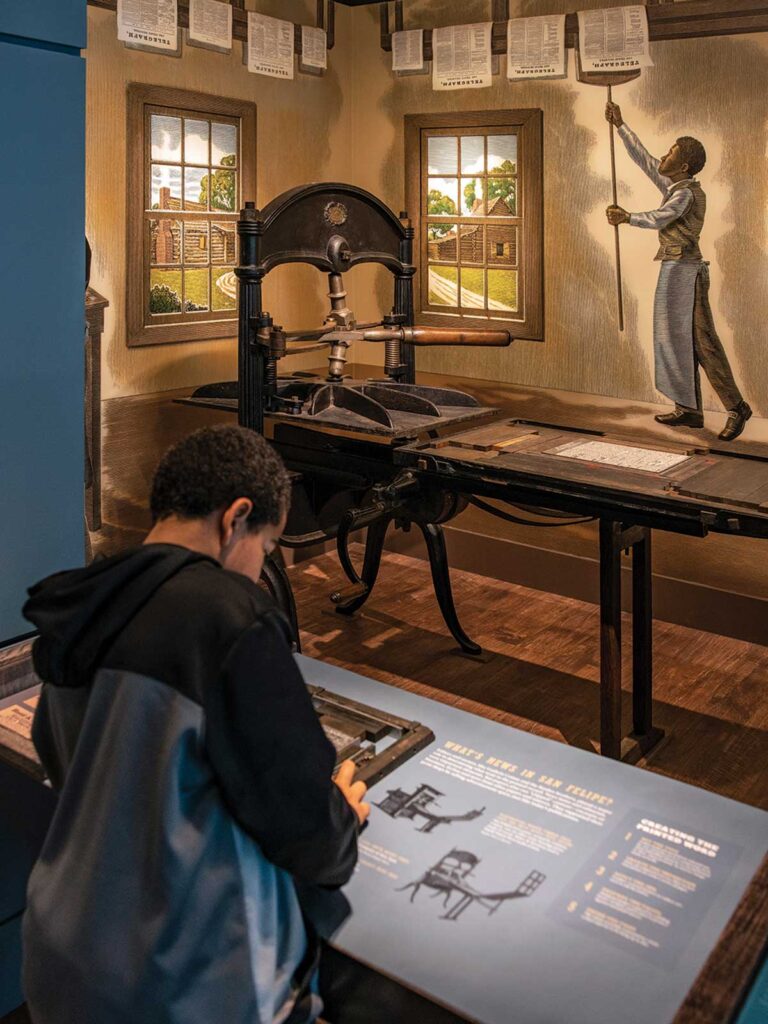

A recreated 1830s print shop features an operating replica press that visitors can help operate.

Courtesy of The Texas Historical Commission

Austin was paid in land, so he sought industrious, steadfast immigrants who would build successful farms and buy town lots. That meant his most pressing priority at first was to survey the colony and lay out the capital. He kept up with important colonial documents in a sturdy traveling desk that is now on display as a centerpiece artifact of the museum.

Geographically, the capital encompassed some 22,000 acres, boasting hundreds of town lots and adjacent farmland. The town rested on a bluff above a ferry landing where the Atascocita Road crossed the Brazos River. As a transportation hub, San Felipe de Austin enabled frontier families to ship products such as cotton and hides in wagons and boats to distant ports such as New Orleans and Vera Cruz, Mexico.

Traders returned with manufactured goods that brought sophistication to the frontier. Shops also stocked items made by local artisans—including blacksmiths and tinsmiths, tailors, hatters, and even a clock maker, silversmith and jeweler. At the town’s peak, it supported a population of approximately 800. Most residents were Anglo-Americans and African-Americans, but there was a small Mexican enclave that provided horses and livery services.

A paved walking trail leads from the museum around the original central business district with interpretive panels explaining what took place on the lots.

Several taverns, most notably Peyton’s Tavern, offered meals, lodging, drinks and space to socialize. Peyton’s patrons included local lawyer William Barret Travis and San Antonio trader James Bowie, both of whom died while defending the Alamo. Robert M. Williamson, an influential local lawyer and early supporter of independence from Mexico, also frequented the tavern. He was known around Peyton’s as “three-legged Willie” because of his wooden leg.

Tavern proprietress Angelina Peyton later famously fired a cannon in another Austin—today’s state capital—to prevent the secret removal of the fledgling Texas Republic’s archives to another town. A statue on Congress Avenue in Austin honors Angelina Eberly (her name following a second marriage) and that daring cannon shot.

Villa de Austin

Several hotels also catered to the steady stream of arriving settlers as well as officials and lawyers in town on business. Visitors today get a real-life look at a frontier hotel in the site’s living history village called Villa de Austin.

A colorful sign welcomes you to the Farmer’s Hotel, a two-story log structure that offered boarding by the day or month. Lodging was important because newcomers often had to stay in town for extended periods while land documents were finalized. The villa’s replica hotel features a brick-lined cellar, similar to the original, which stored kegs, other drinks and barrels of food.

Nearby is a reproduction of an outdoor kitchen and bake oven once used by an enslaved cook named Celia who prepared meals for hotel patrons. Unlike most enslaved residents, Celia gained her freedom in 1832 with help from local lawyer William Barret Travis.

Because San Felipe was the capital, one of the most important businesses was the printing office. The villa’s print shop features a working replica printing press like the real one that printed the Texas Gazette, the first consistently published newspaper in Texas. The shop also printed the first book published in Texas—an English translation of the Spanish decrees that established the colony.

San Felipe garnered a second newspaper when surveyor and Austin confidante Gail Borden Jr. co-founded the Telegraph and Texas Register. The shop opened in October 1835 as Texian frustrations with Mexico’s new leader, Santa Anna, boiled over. Borden and associates began printing broadsides supporting settlers’ demands for independence.

The newspaper’s first issue announced the Texian victory over Mexican troops at the Battle of Gonzales. Subsequent issues were printed almost weekly to inform citizens about the Texas Revolution. It also printed Travis’ Victory or Death letter from the Alamo and the 1836 Unanimous Declaration of Independence signed at Washington-on-the-Brazos.

Before that declaration, Texian leaders had gathered three times in San Felipe to discuss political options and to chart a way forward. The Villa’s replica courthouse and convention hall recreate the original places where those critical councils and conventions took place.

Periodic special events feature pioneer craft skill demonstrations.

Courtesy of The Texas Historical Commission

Hands-on learning helps bring history alive, especially for school-age visitors.

Courtesy of The Texas Historical Commission

Rising From The Ashes

Meandering through the new “old town” of Villa de Austin, visitors learn how San Felipe rose to prominence—and how it reached its demise.

Texian troops experienced a devastating defeat in San Antonio at the Alamo, and triumphant Santa Anna marched eastward to capture the colonial capital of San Felipe de Austin. Settlers quickly fled eastward to stay ahead of advancing Mexican troops. The scramble became known as the Runaway Scrape.

San Felipe’s residents readied their own escape, but first they had to obey an order from local militia leaders. To keep Mexican troops from making use of the capital’s buildings, residents had to do the unthinkable—burn their town to the ground. Santa Anna remained at the burned townsite for several days in early April as he and his troops tried crossing the Brazos River. Weeks later, Santa Anna and his forces were captured at San Jacinto, allowing the Texas Republic to commence.

The new republic carried on without the smoldering ruins of San Felipe de Austin, which never recovered.

“The dramatic destruction of the town kept it from regaining its early prominence, but it also created a unique archaeological record that continues to reveal the town’s history,” said historian Michael Rugeley Moore, who has studied Austin’s colony for more than two decades.

Archaeology may allow for San Felipe’s rich history to rise like a phoenix from the ashes. “Only 10% of the historic site has been fully excavated,” said staff archaeologist Sarah Chesney. “But because the town didn’t rebuild and has seen little development in 200 years, we have much to find. When we excavate down to a black layer, we know that’s the 1836 burn layer. It’s a timestamp that lets us put what we find in historical context.”

Plans are underway for an on-site archaeology lab, she added, so the story of San Felipe de Austin may come into clearer focus as work continues.

“We now have a strong sense of place to tell our story,” said site manager McAuley. “Texans have spent 100 years falling in love with the Alamo, Goliad, San Jacinto and Washington-on-the-Brazos. We’re a part of that story, directly connected to those famous sites, and visitors who come to San Felipe de Austin now will be surprised by what’s here.”

A statue of a colonial family on the move welcomes visitors.

Courtesy of The Texas Historical Commission

The historic town held the first newspaper printed in Texas, as the printing press exhibit details.

Courtesy of The Texas Historical Commission

A replica of the 1830 Farmer’s Hotel, also used as the town hall, a tavern and store.

Courtesy of The Texas Historical Commission