First-person stories provide a stark look at a forgotten chapter of recent Texas history—as well as a warning for the future—in a new book about the defunct Waco State Home.

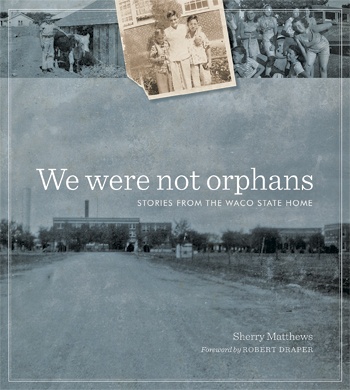

We were not orphans: Stories from the Waco State Home (University of Texas Press, 2011) tells the story of the State Home for Dependent and Neglected Children (renamed the Waco State Home in 1937), which housed and cared for thousands of abandoned and abused children from 1923 until it closed in 1979.

Through a collection of more than 50 interviews with former residents, author Sherry Matthews sheds light on the harsh realities of life at the home.

In the book’s foreword, journalist Robert Draper calls the Waco State Home “the de facto safety net for children who had committed no crime other than the offense of being born poor.” For many of its young residents (who were wards of the state but not orphans), the institution provided education and skills that helped the children establish successful adult lives. But, for others, Draper writes, the home was “part of a Dickensian saga that has remained untold until now.”

Credit for the telling of the story goes to Matthews, who was 3 when her three older brothers were taken away to live at the home. Matthews and her mother traveled from East Texas to Waco to visit the boys during their six-year stay there. As Matthews writes, the family tragedies that sent her brothers to the home are not included in the book’s collection of stories.

But her family’s story, nonetheless, carries great weight. She writes that her one surviving brother, Bing, “says he remembers his time in the Home as the most miserable years of his life and has no story to tell.”

In June 2004, more than 50 years after she had last visited the home, Matthews joined Bing at a Waco State Home reunion. Matthews describes former residents eagerly showing off their old living quarters to children and grandchildren, sharing memories of homemade rolls, fresh dairy ice cream and beloved teachers.

But not all remembrances were pleasant. One woman recounted a harrowing childhood experience at the home. A dorm mother told the girl that she was spending too much time brushing her long, below-the-waist hair and “whacked off all my hair above my ears in this ugly, jagged cut,” the woman told Matthews. “I was devastated.”

In 2008, Matthews contacted members of the Waco State Home Ex-Students’ Association and embarked on the project of telling their stories. She also gained access to thousands of binders of historical materials compiled by Harold Larson, the founder and archivist of the Ex-Students’ Association who died in 2009. Photographs from Larson’s collection accompany many of the stories.

Many former students describe lives of destitution before coming to the home. Dick Hudman conveys the 1920s-era agricultural depression in a few flat statements: “I had three brothers and a sister. My dad died after being kicked by a mule. My mother couldn’t take care of us, so she sent all the boys to the Waco State Home. … That was in 1924, when I was two years old. I grew up there.”

Betty Emfinger Cupps, who was at the Waco home from 1948 through 1951, says of life before the home: “We were neglected. I remember going hungry, and I remember my brother, James, and I eating dirt to fill our stomachs.”

Yet some of the home’s former residents tell of heartbreak at being taken from their families. Betty Ann Moreno Dreese, who arrived in Waco in 1944, tells of weeping for days after her arrival and being given “a room with a window that looked out on the front gate, so I could watch for my mother. I watched and watched, but she never came.” Help, as Dreese describes, arrived in the form of Mr. Speece, a coach, who started visiting the girl: “He told me he could really use me on the basketball team. He even brought me a basketball.”

Other teachers and staff members helped students in immeasurable ways. Dreese says of English teacher Mabel Legg: “She taught us to love poetry and all the things that make a child’s life beautiful.”

Charles Goodson, who went to the home in 1939, describes the tough-love approach of Superintendent Ben Peek: “When I left the Home, [he] looked me straight in the eye and told me I would never amount to anything. I am not saying he was a bad guy. He wanted me to stay and finish high school. He cared about us.”

Goodson ends his story with a glimpse at his adult life: “Now with six figures in the bank due to hard work five or six days a week, I intend to hunt and fish and spend money in my retirement.”

Ronnie Corder, who came to the home in 1965, recalls landing a part in the play “Oliver!” and being asked to sing. Corder told teacher George Weaver, “I can’t sing anything,” and Weaver said, “Well, we can practice together.” And so they did. The play, Corder says, “changed my life and made me think somebody really cared.”

But, as Matthews details, there was a dark side to the home, which was under the supervision of the Texas Youth Council (TYC). In 1971, a federal district judge found that a number of practices—including arbitrary beatings and solitary confinement—routinely being practiced at TYC facilities constituted cruel and unusual punishment. Because of his ruling, the Waco State Home was eventually closed as a facility for dependent children.

Matthews reproduces previously hidden records from a Texas State Board of Control’s investigation some 70 years ago that ultimately ended in the dismissal of the superintendent. But sadly, as she describes, pockets of abuse were allowed to fester for decades more.

Matthews, who runs an Austin-based advocacy marketing firm, concludes that the Waco State Home’s alumni are “heroes for us all.”

And she writes with a simmering rage that serves as a wake-up call: “An obvious reason for indifference toward the abuse of dependent children was simply prejudice against poverty. It existed then, and it exists today.”

——————–

Austinite Joel W. Barna is the former editor of Texas Architect magazine.