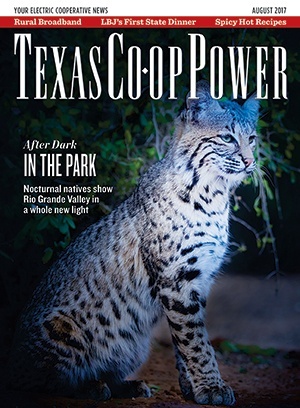

Are you willing to roam the woods at night, alert to the sounds of armadillos, frogs, owls and bobcats?

In the dark—when our eyes try to make sense of shades of black and gray—people feel less secure and tend to group up, a strategy that helped our ancestors survive.

“When it gets pitch black out, the superpowers we have within us start coming out,” says Laurentee Acevedo, an administrator at Resaca de la Palma State Park near Brownsville. “At night, we rely more on other senses: listening, smelling and using dark-adapted eyes.”

Three Rio Grande Valley state parks offer night tours and a chance to explore parklands rustling with wildlife in the company of a knowledgeable guide. It’s an easy way to take back the night and enjoy parks safely after dark. Across Texas, state park programs vary with the seasons and the moon. Owl prowls, haunted hikes, stargazing events and creatures-of-the-night tours give you good reasons not to be afraid of the dark.

On a moonless Family Fun Night, Acevedo leads the after-dark tram tour that takes us to what feels like another world. “The key is, everybody has to be quiet so we don’t scare the animals,” says Ron Karter, park host and tram driver, as two electric trams filled with family groups and Cub Scouts silently roll through 1,200 acres of resaca wetlands, thorn scrub and Texas ebony forest. The headlights illuminate midnight-dark patches in the road that suddenly rise up and fly off. These are pauraques, the Rio Grande Valley’s year-round nighthawks, easily identified by their wide, froglike mouths.

The electric tram stops, and we hop off for a 15-minute walk down Mexican Olive Trail. We observe and duck under spiderwebs strung from branches thrusting out from tangled thickets of guayacan, soapberry and ebony. Excited by the dark surroundings, the Scouts swing their heads, and their headlamps momentarily blind other members of the group. We can feel the increased humidity and smell the slightly swampy tang of water nearby, and in a couple of minutes, we reach the resaca for which the park is named. Our guide explains that leaves from the black willows around us were used in teas to cure headaches.

We stand on the bank of this former Rio Grande channel, now an oxbow lake, and see the stars overhead as clouds move across the night sky. A spotlight catches the eye shine of an owl flying low and fast across a nearby field.

On another night tour—Estero Llano Grande State Park’s Full Moon Party—ranger John Yochum gives us a preview of what will be moving around in the dark. He suggests we look out for bark scorpions, raccoons, nine-banded armadillos and opossums. “It’s a new world at night,” he says, “We’re always exploring. Coyotes are easier to hear than see.”

Because we have a full moon to illuminate our path, Yochum discourages flashlights except when they are needed to pinpoint the source of a noise or catch the eye shine of a nocturnal creature. What I hear are leopard frogs, which sound like heavyweight hens clucking.

Venturing down the trail, we wade through an aromatic fog from the blooming coma trees and tune in to the tree crickets chirping. A bird rustles the leaves of a low tree, and wings beat past us. “If it flies and is noisy, it’s a dove. If you can’t hear anything, it’s an owl,” Yochum says.

Estero Llano Grande, near Weslaco, features eight resident alligators that move between ponds, Yochum tells us as he plays a spotlight over Alligator Lake. Because those reptiles rank as my No. 1 scary creature, all my senses are on alert, and I’m ready to flee. What looks like white lights on the end of a 7-foot-long log? That’s the reflection from alligator eyes. Thank goodness they are on the far side of the lake.

The ranger directs us to hunt for bark scorpions. We wave small black lights across the bark of mesquite trees and the grass along the path until Yochum finds the first one. It shines with a luminescent sheen. Every leg and abdomen segment is visible, as is the wicked-looking curved tail that houses the stinger. Night-hike explorer Karen Fossum discovers another scorpion, which poses, unruffled by our gasps of excitement and countless cellphone photographs.

Under the full moon, Yochum introduces us to the free Google Sky app. Install it and point your cellphone at the sky, and the app identifies the planets, stars and constellations in the phone’s line of sight.

On the wetlands boardwalk, I hear black-bellied whistling ducks overhead and the splashing of moorhens. Ranger Lorena Guerra tells us the folktale of La Lechuza, the witch who turns into a barn owl and chases children who wander outside after dark. “It screams and hisses instead of hooting, which makes it seem more creepy,” she says. “Many people are still afraid of barn owls because of stories they heard as children.” Amid all the night sounds, I am happy not to hear the dying-animal scream of woodhouse toads.

With the coastal zone overlapping the temperate, tropical and desert zones in the Valley, the range of environments ensures exceptional biodiversity. “It’s different every time,” says Amber Schmitt, lead interpreter at Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park in Mission, as we begin a two-hour Creatures of the Night tram tour at twilight. “Some people think it is boring at night with nothing happening, but if you stop and listen.”

We listen at the Kingfisher Overlook. Schmitt holds up a bat detector that translates bats’ high-pitched echolocation calls into cricket-like chirps. That lets us pinpoint the location of the bats fluttering above the pond in the purple-streaked western sky. “Northern and southern yellow bats roost in palm fronds in the park,” Schmitt says. “At this time of night, they’re flying above the water to eat insects. Their faces funnel sounds to their ears.”

Why would animals be nocturnal? Many reasons: The darkness makes it more difficult for predators to see them; their preferred food is often more accessible; and nighttime activity requires less water.

The art of spider sniffing, Schmitt shows us, involves holding a flashlight up at ear and eye level. Suddenly we see dozens, or even hundreds, of sparkles in the grass: These are reflections from eyes of spiders all around us. “They are all over! It’s like someone dropped glitter,” says a startled Gayle Yepsen, visiting the park from Illinois.

Schmitt explains that many night animals have a reflective surface at the back of their eyes. She shines a red laser beam on a sparkle to reveal a hefty wolf spider.

Black lights in hand, we search for more bark scorpions and find an abundance of them glowing. “The more gnarled the mesquite, the more it is likely to have bark scorpions,” says Schmitt. Some tour participants are distracted from the scorpions by the luminescence of plastic forks, weed trimmer line and even shoelaces.

The wind shakes the mesquites, but I spot movement nearby. It is a white stripe undulating in the dark. A skunk! The tram rolls on as we sweep lights over the dense woods. We spot an eastern screech-owl, watching us watching it. An armadillo scuttles away from our group. Cicadas pitch their incessant messages. At a bird blind, snout butterflies are nectaring on orange halves set out by park staff, taking advantage of the darkness to get their turn at the food.

Circling back toward park headquarters in the tram, we spot three javelinas digging with their snouts for grubs and roots, but they retreat from our lights. Two more skunks run in front of the tram, so we slow down.

With the weather determining what creatures come out, Schmitt says, “It feels like an entirely different park at night.”

——————–

Eileen Mattei is a Harlingen writer and Texas master naturalist.