Austinite Jim Comer wrote about caring for his parents, Anne and John, in the July 2005 issue of Texas Co-op Power. His original book, Parenting Your Parents, has since been expanded and reissued by Hampton Roads Press and titled When Roles Reverse. This compassionate and practical account of one man’s experience with his parents is available at bookstores everywhere. In this excerpt, Comer’s parents are in the same nursing home but living separately. His mother has Alzheimer’s.

This is the chapter I didn’t want to write. A few months after his 95th birthday, Dad’s health began to fail.

In the summer of 2005, something happened. I wish I could be more precise, but the doctors and nurses were equally baffled. Was it dementia or the onset of actual Alzheimer’s? Had he experienced a series of subtle strokes? Whatever physiological shift occurred, it led to shouted symptoms.

Dad began to cry out, “Help me, help me! Please, help me.” He repeated that plaintive plea over and over from wheelchair, bed and toilet seat. Like a child screaming for attention, he was relentless and unyielding. He might say the phrase several hundred times in one day. While his emotions spun out of control, his vocal cords lost none of their strength. “Help me, please!”

When I walked into the nursing home, often I heard him in the lobby 50 yards down the long hall from B-Wing. When he saw me, his eyes widened, and the volume increased. I would give him a hug, but I was never able to reassure him.

An internal burglar alarm had been activated. None of us—doctors, nurses or administrators—had the correct code to disable it.

Although I knew the nonstop cries were not my father’s fault, they were—as the months dragged on—maddening. More than once, I heard myself saying, “Dad, you’re OK. There’s nothing wrong. Everything is fine.”

What a stupid thing to say. Everything was not fine. Of course he was agitated, anxious and depressed. I would have called for help, too. Only I wouldn’t have said “please.”

The staff remained amazingly patient. The nurses’ aides would hold his hand, give him hugs, and offer orange juice or his beloved vanilla ice cream. Mostly they gave him their attention, providing far more than our money’s worth of kindness and affection, even though Dad was just one of many needy residents.

Dad’s doctor requested permission to give him medication for anxiety and depression. I told him to do anything that would relieve my father’s fears but not leave him drugged and half-asleep.

Sunday December 18

One week before Christmas, I stopped by the nursing home after church and found Dad slumped over in his wheelchair. He often snoozed in that chair but never slumped. He looked more fragile than I’d ever seen him. I had the nurse call the doctor and let her know there had been a marked change in his condition.

Monday, December 19

After a 6:45 a.m. Toastmasters meeting, I had three messages on my cell phone. The nursing home and both cousins had called to say that Dad had taken a sudden turn for the worse, was on oxygen and might have to go to the emergency room. By the time I got to the nursing home, the administrator, head nurse and social worker were at his bedside. Two doctors arrived and told me that Dad was dying.

Although I took in the words, they did not fully register. Other people died, but not my dad. Didn’t those doctors know he’d flown 76 combat missions over Germany during World War II and lived? Couldn’t they see those portraits of B-17s on his wall? This man was a survivor. Last week he was rolling himself down the corridor raising a ruckus. Now he had “a day or two to live.”

Instead of moving him to the hospital, we agreed to keep him in the nursing home, where his surroundings were familiar. My cousins said they would help me take turns staying with him, and we made out a schedule.

By noon everyone had left the room, and I was sitting alone with my father. Suddenly Dad roused himself and started trying to get out of bed. He managed a feeble, “Help me, help me.” For the first time that phrase sounded good to me.

At 5 o’clock, one of his favorite nurses’ aides, Jackie, determined that Dad would eat something. Even though he said “No,” she would not be deterred. She coaxed, persuaded and demanded that he take “just one spoonful” and then another. I watched her feed him, bite by grudging bite. She held the spoon 1 inch from his lips, willing him to open his mouth.

Tuesday, December 20

Dad’s oxygen level had stabilized, and his color had improved. The doctors said their previous day’s prediction was wrong. Dad might last a week or two. They called Hospice Austin, and 45 minutes later I got a call. Hospice wanted to know if they could send a social worker to the hospital for an intake interview. I said, “Sure. What day will they come?”

“In an hour.”

“An hour?”

“Is that too soon?”

“No, that’s amazing.”

While Dad slept, I remembered that I needed to check on Mother. I walked 30 seconds down the hall to the dining room where the annual nursing home Christmas party was in full swing. The laughter, music and energy of life stood in stark contrast to the room I’d just left.

The staff had worked for weeks to transform the large dining area with colorful decorations. I found Mother at the back of the room and sat down next to her. Since there was chocolate cake on her plate and two cute children visiting a grandmother at the next table, she was in excellent spirits.

Mother didn’t recognize me, but her social skills were faultless.

“Where’s your cake, Honey?”

Good question. I walked to the front of the room to get my sugar fix when suddenly the holiday spirit overtook me—or maybe I just lost control. Two guitars were playing a catchy Latino tune. Without plan or warning, I started dancing around the middle of the room, making up moves as I went along. Soon there was clapping, so my steps got bolder. I recruited an unsuspecting staff member as a partner, and we began improvising across the floor. I’m sure we looked like failed reality show contestants, but a little dancing was just what the party needed.

The administrator handed me a microphone and said, “You’ve got to sing.” I looked at the elderly pianist and said, “How about ‘O Holy Night’?”

“What key?”

“Your guess is as good as mine. I don’t read music!”

“Don’t worry, I’ve heard it all. We’ll fake it.”

As I belted out “O ni-ight di-vine” I saw that Mother had been wheeled up front and was smiling at me. When I finished the song, I went over to her. A woman standing next to her said, “When your mother heard the first line of your song, she said, ‘That’s my boy singing!’ So I brought her up close so she could see you.”

Mom hadn’t known who I was for a year, but she recognized my singing voice from a hundred feet away. That was the best Christmas present I could get; I received the gift of recognition. Her temporary moment of memory restored my perspective. Dad might be terribly ill down the hall, but Christmas was coming, full of joy, possibility and hope.

Wednesday, December 21

The hospice nurse arrived promptly, checked Dad’s vitals, talked with the doctor, and arranged for morphine to be administered orally when needed. I began to understand why so many friends had told me how hospice care had been a blessing to their families.

The most powerful image of Dad’s last week was the time I spent alone with him, by his bed, forced to face the fact of his impending death. I’d never kept watch by the bedside of a parent. This was new territory for me.

Thursday, December 22

Dad had stopped talking, though his presence remained powerful. Lying there, eyes wide open, he gazed intensely at the ceiling. As I stood above his bed and looked down, he stared through me at a landscape beyond my range of vision. I held his hand, amazed by the strength of his grip, and told him loudly that I loved him. I wanted to believe that he heard me, though I doubt he did. Dad was focused on only one thing: his next breath.

Sunday, December 25

As I walked down the hall of B-Wing, I could see bright boxes being opened and families gathered around beds doing their best to import joy. At the nurses’ station, lights were twinkling, decorations glistened and the atmosphere was resolutely cheerful. As I walked into Dad’s room, I realized that for the first time since grade school, I had no present for my father. This year my gift was being there.

I sat with him for hours, thinking of Christmases past: the time he couldn’t get my electric train set up and the year of the yapping puppy hidden in the basement. I recalled long trips in big cars crowded with presents. I wondered what Dad was thinking, or if he was thinking at all.

Monday, December 26

As Dad slept peacefully, I went to get Mother so she could visit the husband she no longer knew. When I brought her into his room, the nurse was bending closely over Dad’s face, checking his breathing. I walked over to the bed. The nurse checked his pulse. Half a minute went by and she said, “I think your Dad just took his last breath.”

Dad had died seconds after Mom and I walked into his room. We had no warning. Nothing dramatic happened. There was no gasping for breath or sound of a struggle. He simply stopped breathing and tiptoed out of our lives.

I’d never seen anyone die, much less my father. I stood there looking at him, trying to take in what had just happened.

I put my arms around Mom’s shoulders.

“Mom, Dad has gone to heaven.”

“He has?”

“Yes, he’s not sick any more.”

“That’s good.”

She seemed to have no trouble with the concept of death for the few seconds she considered it. As we headed back to her room, she had forgotten the news before we passed the nurses’ station. Part of me envied her.

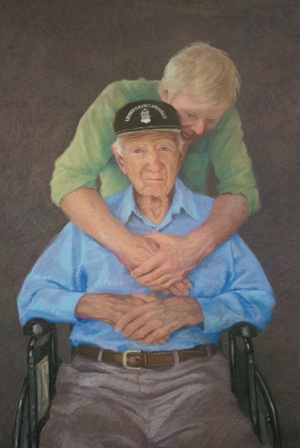

Mary Close, who lives in Lakeville, Connecticut, is an oil and pastel painter whose subjects are often elderly couples or elderly people with their families.