With its medical system in tatters after 14 years of civil war, Monrovia, Liberia, greeted the arrival of the 500-foot hospital ship Africa Mercy with dancing on the quay and a massive health screening held in a stadium.

Instead of bombed-out hospitals, unsterile operating rooms, sporadic electricity and a national medical staff numbering in the mere dozens, the May 2007 docking of the Africa Mercy—which sails for a global charity called Mercy Ships—meant the sudden appearance of a sterling 78-bed ship with six modern operating rooms and a full medical staff included in its 450-member-plus crew.

Those in the screening lines were testament to the West African nation’s staggering poverty: men disfigured by massive facial tumors; children limping on club feet or with war wounds; young women suffering from childbirth injuries rendering them incontinent and outcast from their homes and villages.

“In a country with 85 percent unemployment, there are a lot of needs,” Mercy Ships CEO Samuel Smith said. “You will go to an orphanage with 250, 300 kids, and they are standing there with two shoes that don’t fit, tattered T-shirt and shorts, and that is all they have.”

People from more than 30 countries volunteer to work for Mercy Ships, which has been sailing hospital ships to the world’s neediest corners for 30 years, delivering free world-class health care and community development services to the forgotten poor. Mercy Ships recently retired two smaller ships as the Africa Mercy came on line, leaving it as the only ship in active service. The Africa Mercy, the world’s largest charity hospital ship, doubles Mercy Ships’ former capacity.

Since 1989, when the faith-based Mercy Ships charity moved its headquarters from expensive California to modest Garden Valley, a tiny hamlet on Wood County Electric Cooperative lines northwest of Tyler, it has taken on more of a Texas twang, with Texans heavily represented among its volunteers and supporters.

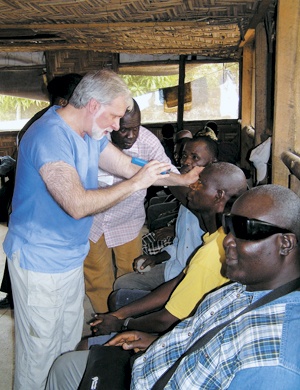

Dr. Glenn Strauss, a 53-year-old Port Arthur native, is among the most thoroughly committed Lone Star volunteers, having closed his long-established ophthalmology practice in Tyler at the end of 2004 to work full time for Mercy Ships, along with his wife, Kim.

“Some of the earliest medical mission trips I went on were mostly well-wishing,” Glenn Strauss recalled. “You made a representation that you cared, but as an eye surgeon you can’t accomplish much without the proper facilities.”

Mercy Ships’ strategy of bringing the hospital to the patients, complete with a staff that does not need to worry about finding safe food or adequate shelter in parts of the world where both are rare, meant that he could make the most of his time with patients, Strauss said.

In 1997, Strauss started making short-duration trips on ships, working in sub-Saharan Africa and Central America. After their children were grown, the couple made the leap to join the organization full time.

“While we in this country suffer from diseases of excess, like heart disease, they suffer from diseases of lack of access,” Strauss said of West Africa. “What this means is that minor problems become horrendous problems. A small facial tumor might eventually suffocate someone. A cataract here that makes it maybe a little frustrating to drive at night, you get it taken care of. There, they grow so thick and dense and they can’t see light. They go blind.”

In African tribal societies, people with deformities such as cleft palates or lingering maladies are seen as cursed and often banished from their families and villages.

“The blind are a burden to their families and the whole community,” Strauss said. “The way they look at it, this is fate. They need to be put out. So when we restore someone’s sight, we restore them to their community. That is the basic strategy for the types of cases we do and why we do it.”

On the Africa Mercy’s initial trip to Monrovia, Strauss performed the first eye surgery in one of the ship’s two operating rooms dedicated strictly to eye care. His patient, Suah Paye, a woman in her 90s from a small village called Oil Town, had gone blind with cataracts three years earlier. Although neighbors scared her with stories about how she would most likely die on the operating table—or have her eyes removed and washed with soap—more sophisticated family members living in the capital city guided her to the ship. Her sight restored by Strauss before she left the operating table, she danced through the operating suite singing and praising God.

The largest nongovernmental hospital ship in the world, the Africa Mercy is capable of performing 7,000 surgeries annually, with an emphasis on cataract removals, cleft lip and palate reconstruction, orthopedics, tumor removal and repair of birth injuries that afflict more than 80,000 African women each year.

Like most Mercy Ships volunteers, from doctors to captains, the Strausses pay their own way to serve. So far, contributions from former patients, neighbors, relatives and medical colleagues going back to when Strauss taught at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston have kept the couple in the field.

“Every volunteer will tell you the same story: It’s a labor of love,” Smith said. “Everybody is here for no other reason than to help people in need.”

——————–

For more information, go to www.mercyships.org.

Thomas Korosec is a freelance writer living in Dallas.