One of Texas’ legendary figures grew up with the state. Charles Goodnight was born March 5, 1836, in Macoupin County, Illinois, just three days after Texas achieved independence. Goodnight came to Texas riding bareback into Milam County, 30 miles northwest of present-day College Station, in late 1845, the year Texas joined the Union. Goodnight was proud of those dates, and some biographers suggest it was this close chronological identity that inspired him to lead a life that followed such a sweeping arc across the Lone Star State.

Goodnight made history for his gutsy cattle drive with partner Oliver Loving. The two blazed a new trail to lucrative markets in the west through hostile Indian territory. The tale is familiar to fans of Larry McMurtry’s epic novel “Lonesome Dove” and the star-studded miniseries borne from the book, but even without the embellishment of Hollywood, the real story describes an epic journey. Today’s history buffs can follow Goodnight’s trail through Texas, beginning where he did, in the tiny town of Oran.

Goodnight was still a young man of 30 when the Civil War ended. After serving as a scout for the Texas Rangers and as part of the Confederate frontier defense, he returned to the rough country of north-central Texas to find that uncontrolled cattle rustling had left untamed herds roaming the landscape. Goodnight was devastated and saw little cause for hope.

But that hopelessness and desperation spawned a daring idea. Popular trail drive logic directed cattlemen to aim for northern markets at trailheads in Kansas and elsewhere by following proven routes such as the Chisholm Trail. Knowing that with risk comes the promise of greater reward, Goodnight turned his sights west, betting on the underserved markets of New Mexico and Colorado. For this unprecedented plan to succeed, he would have to navigate the edge of the Comanche-controlled regions of the Panhandle and drive the cattle first south and then west for three days across the dry and featureless Llano Estacado.

As the upstart Goodnight prepared for the never-before-attempted drive in spring 1866, he traveled to nearby Weatherford and met up with Loving, an established cattleman almost a full generation older, who was then gathering his own herd for a drive. Goodnight recalled the chivalrous tone of that meeting at Black Springs, present-day Oran, years later.

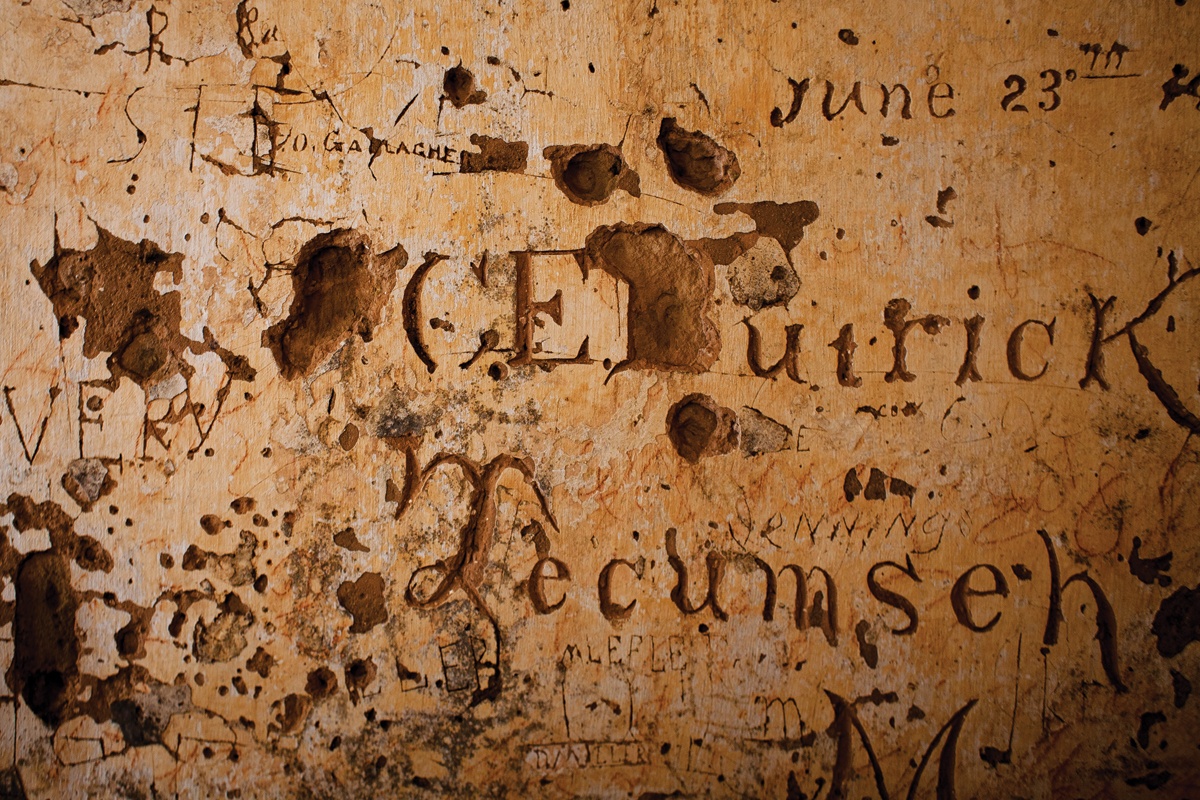

Two historical markers acknowledge that historic Goodnight-Loving partnership in Oran. A thriving trade center in cattle-drive days, Oran today seems an unlikely spot for the genesis of any historic undertaking: Only a clutch of battered buildings and down-at-the-heels houses define the town now. On the eastern edge of the Keechi Valley, FM 52 traverses hilly prairies interspersed with mottes of oak.

As the legend goes, Goodnight and Loving combined herds a few miles southwest of Fort Belknap on the western banks of the Brazos River. In early June 1866, they moved southwest with a herd estimated at 2,000 head managed by fewer than two dozen men and followed by a surplus Army wagon that Goodnight designed to serve as the outfit’s chuck wagon. Today, the Texas Historical Commission’s Texas Forts Trail follows the early sections of the original Goodnight-Loving Trail, marking a path southwest toward San Angelo.

Goodnight’s biggest gamble came west of San Angelo. The hands led the cattle to the Middle Concho River, where man and beast consumed as much water as possible in preparation for a near-100-mile trek across a barren and arid plain that would last three days and nights.

After that grueling, waterless drive, the herd stampeded for the Pecos River. The ensuing crush to relieve their torrid thirst created bedlam for cowboys, horses and cattle: A hundred head were lost.

Despite these losses, Goodnight and Loving pushed on north to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, where the U.S. Army bought much of the herd. Loving managed to guide the remaining cattle on to Colorado, while Goodnight returned to Texas carrying a relative fortune in gold with dreams of even greater rewards.

In 1867, in the course of the partners’ final drive, Loving made plans to travel ahead of the herd. He was wounded in an attack in New Mexico, just north of today’s state line, and succumbed to his wounds not long after.

Goodnight not only continued to pay Loving’s heirs his share of the business proceeds after Loving’s death but also promised to return Loving’s body to Texas. It wasn’t long before Loving returned home to Weatherford. An iron fence surrounds Loving’s grave on a hill in the Greenwood Cemetery overlooking the picturesque downtown neighborhood and the Parker County courthouse.

Goodnight continued ranching, working his cattle in the arid Llano Estacado country. He founded the JA Ranch with Englishman John Adair and established his own herds in Palo Duro Canyon. A replica of the one-room dugout he burrowed into the red clay earth of the canyon walls and roofed with cedar and cottonwood logs is open to tourists in Palo Duro Canyon State Park. Visitors to the “The Grand Canyon of Texas” can hike among colorful sandstone formations that Goodnight considered “nature’s fencing,” as it kept his cattle from wandering in those early days of Texas ranching.

As the American bison numbers dwindled in the late 1800s, Goodnight’s wife, Molly, encouraged him to save several orphan calves. In doing this, Goodnight established one of the five buffalo herds remaining in North America today. Descendants of this herd became the official Texas State Bison Herd in 1996 and now roam freely on 10,000 acres in Caprock Canyon State Park. Driving that park’s scenic loop, visitors can encounter buffalo bulls nibbling grass at the road’s edge and witness new calves testing their legs.

The Goodnights built their homestead north of Palo Duro Canyon and founded the town of Goodnight. The home was restored and opened to the public as the Charles Goodnight Historical Center in 2013. The two-story Victorian house, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, sits just south of U.S. 287, 40 miles east of Amarillo.

With the Goodnight house as the center of an imaginary compass, Goodnight’s legacy appears today to reach in every direction: To the east, his humble beginnings in the Keechi Valley. To the west, traces of the Goodnight-Loving Trail. To the north, the almost-deserted town of Goodnight that he founded in 1887. A historical marker on Ranch Road 294, just past Juliet-John Road, marks the site where Charles and Molly established the Goodnight College in 1898, a coed academy for the children of settlers and ranch hands. To the south, the JA Ranch, one of the most renowned ranching operations in the Texas Panhandle.

Late in life, Goodnight became known for his abrupt manner and quick temper. Even so, he remained active in ranching and civic life. He is credited with Armstrong County’s first wheat crop, among other agricultural experiments. He also developed a friendship with Quanah Parker, one of the last Comanche chiefs.

Goodnight died early on a December morning in 1929. His remains now lie next to Molly’s in the cemetery in Goodnight. The cemetery occupies a slight elevation, just a short, 2-mile ride from the Goodnight homestead and north of U.S. 287. Dozens of handkerchiefs tied to the fence flutter in the breeze, paying silent homage to a man who grew up with Texas and was one of the last cowmen to experience the open frontier.