My first job when I moved to Austin in 1973 was at a salvage company on what was then the southern outskirts of town. Three of us, all fresh from Lubbock and eager to work anywhere as long as it was in Austin, showed up in response to a help-wanted ad in the paper. A fourth Lubbock expatriate would arrive on the scene a few days later.

The boss, a bald-headed, energetic, middle-aged man, interviewed us one by one. I was the first to meet him. Where, he asked, was I from? When I said Lubbock, he reacted liked I had just said, “China.”

“I was in Lubbock—once!” he answered, excitedly. Then he calmed down a little and told me a story about when he was driving to Lubbock one night and ascended the Caprock and kept cruising toward the Lubbock lights he saw glimmering in the distance. “I drove for an hour, and the lights never got any closer. I couldn’t believe it!”

Apparently, this disbelief, combined with all the coffee he had been drinking, made him particularly anxious to arrive, if not in Lubbock, at any place with a restroom. Finally, with no one else on that long, lonesome highway and the Lubbock lights still not any closer, he stopped his truck in the middle of nowhere and got out.

What he didn’t fully realize was that the weather had changed on him somewhere around the Caprock. A bitterly cold north wind was howling about 30 miles an hour across the Llano Estacado, and the shock of it, when he stepped out of the truck, caused him to have the kind of accident he hadn’t had since he was a little boy. He held the city of Lubbock responsible for this, but I got the job, anyway. I didn’t even have to mention that I was a published writer. Ernie, Steve and our friend, Doak, were all hired and assigned jobs, each to our abilities.

Ernie was by far the most responsible and mechanical of all us, so he was given the job with the most responsibility: operating The Shredder. (Like all monsters, its name deserves to be uppercased.) The Shredder was the central piece of machinery at the salvage company. A unique subculture of folks would bring in abandoned cars and sell them for junk by the pound. The Shredder then chewed them into small pieces of metal that moved up a conveyor belt and emptied into a pile of junk on the ground.

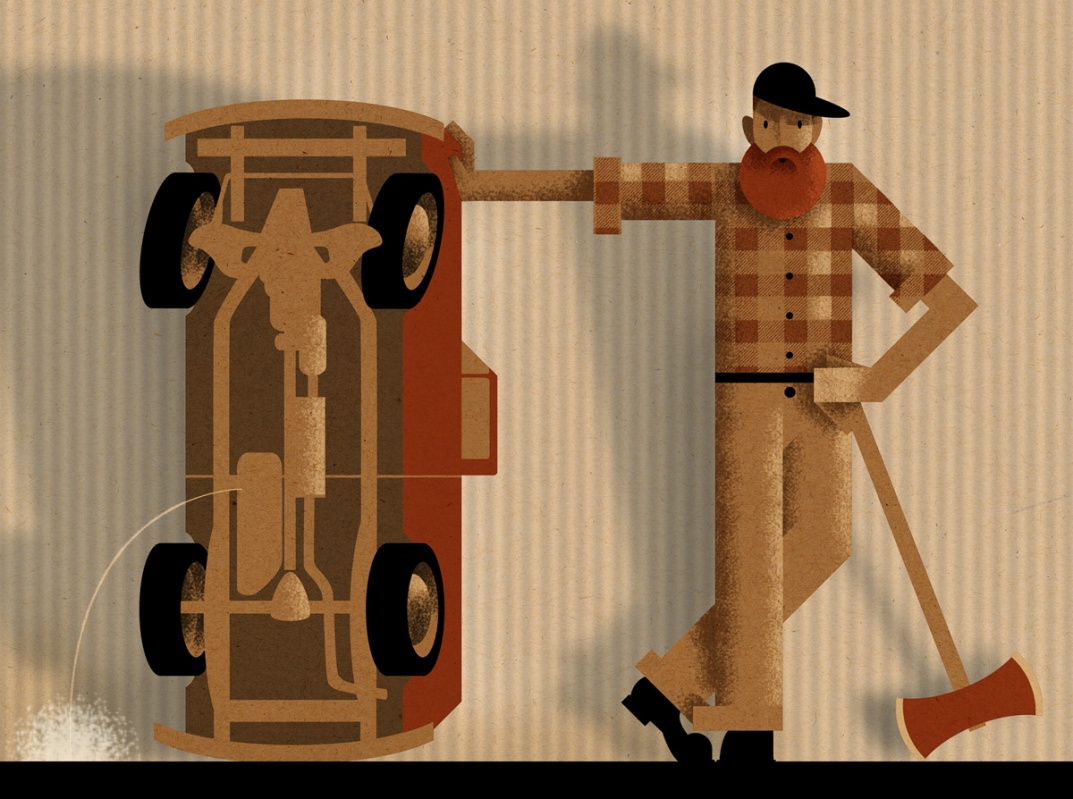

Steve was given an ax, which, combined with his red beard and lumberjack build, made him look like a lot like Paul Bunyan. He was told to chop the gas tanks out of the vehicles before Ernie hoisted them into the jaws of The Shredder. This was to prevent any gasoline that might have been left in the tank from igniting and exploding when The Shredder went to work on it.

Because I had no identifiable skills, I was the handyman. I got all the menial jobs, such as cutting the stems out of inner tubes.

Doak joined the crew a few days later and was sent to the crow’s nest at the end of the conveyor belt with instructions to knock all the nonmetal stuff like upholstery and seat-cushion foam off the belt and into a pile of nonmetal junk. Then a truck would come and take all the metal to San Antonio. The operation hummed like a well-oiled machine, which The Shredder actually was.

Then one day it went “Bang!” And most of South Austin heard it.

Here’s what happened: There usually weren’t any cars waiting to be shredded when we arrived at work, and it took awhile for Ernie to get The Shredder cranked up and ready to go. For the rest of us, there was a certain amount of dead time right after we clocked in. Steve had developed the bad habit of crawling into one of the pneumatic tubes at the base of The Shredder and catching a few extra winks of sleep before Ernie blew a horn to let everybody know the action was about to begin.

On that particular morning, Steve was slow climbing out of the tube and didn’t have time to chop the gas tank out of the waiting pickup before Ernie maneuvered a giant magnet over the old truck and hoisted it airborne on its way to The Shredder.

Steve and I laid odds on the probability of the truck having any gas left in the tank. Steve said they usually didn’t, which was about the time The Shredder blew up. More accurately, it blew out. It was equipped with explosion doors that flew open in case something like this happened. Otherwise, Ernie would have been launched into orbit.

As it was, Doak was the only who got any airtime; he bailed out of the crow’s nest to the ground many feet below. From his vantage point, Ernie heard the boom, saw smoke roll out from the explosion doors and Doak’s rapidly descending silhouette. Doak hit the ground, rolled, and went running for water because, judging from the amount of smoke, he was certain there was fire.

Doak bruised his knee and the boss chewed out Steve, but business went on pretty much as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened that day. The case could be made that nothing had.

We didn’t stick around, though. We found what Doak described as “a dream job.”

We drove ice cream trucks for the rest of the summer.

———————–

Clay Coppedge, a member of Bartlett EC, lives near Walburg.