As night falls over the West Texas mesas, civilization recedes into the shadows. The vast dark sky, studded with countless sparkling stars, and the road ahead lit by headlights is all I see as I drive north toward Sweetwater on State Highway 70.

Then blinking red lights appear on the horizon. First, only a few. Then, a veritable net of them. Little red lights fill the sky as if zealously decorated for Christmas. Driving closer, I see hundreds of towers, each with two red lights signaling aircraft of their presence.

And what a presence they are. I’m heading toward the three largest wind energy projects in the United States.

The scene is repeated across much of the Rolling Plains, West Texas and the Panhandle—country where the dark night sky dominated for eons and captured the imaginations of guitar-strumming cowboys who slept beneath it. The blinking red lights mark the country’s new behemoths—wind power turbines.

In the daylight, the lights give way to a vista of white, monolithic three-armed giants, some of which sprout from the world’s largest wind farm, the Horse Hollow Wind Energy Center with 421 turbines sprawling over 47,000 acres in Taylor and Nolan counties. That’s just one of the wind farms in these two counties that compose about 40 percent of Texas’ wind power production today. Towers are going up so fast across West Texas that the count will be different next week. Part of the boom has been spurred by federal tax credits for wind turbine construction scheduled to cease at the end of the year.

There were 109 wind turbines installed in Texas in 1995 and 897 during 2007, according to the Alternative Energy Institute at West Texas A&M University. The average rating of each turbine escalated during that period from .72 megawatts (MW) to 1.82 MW. The heights of the towers have grown from an initial 80 feet to an average of 260. The huge, sweeping wings can revolve at as many as 21 times a minute.

Some energy experts in Texas believe wind farms are being overbuilt, but there’s no question that the wind business is booming. In the dusty parking lots at wind farm construction sites and at motels from McCamey to Snyder, out-of-state license plates on pickups and cars tell a story of economic opportunity. There’s a shortage of trained assembly technicians across all the windy plains states.

On a sunny November morning, we cruise wind farm territory where Big Country and Taylor electric cooperatives provide the local electric power, including the backup electricity for wind farms’ on-site operations. Scurry County boasts the tallest wind tower in America—345 feet—at Enel North America’s Snyder Wind project. By comparison, the Statue of Liberty is 305 feet. A news release from the project says it will produce 63 MW—enough power for more than 12,000 Texas homes annually. However, it’s important to note that the intermittent nature of wind power means it can’t get the job done alone. It has to be supplemented by a steady source of electricity such as that derived from natural gas or coal. Otherwise, our homes could be lighted and cooled only when the wind was blowing—and it blows the least in the sweltering heat of summer afternoons. All told, the present Texas wind industry has the capacity to produce about 5,000 MW of wind energy, but the transmission capability for only about 3,400 MW. Last year, a little less than 3 percent of the state’s electric power was produced from wind.

Our route to wind country should have taken us past the Price Daniel Detention Facility, but traffic is being diverted. Ahead, a convoy of trucks is preparing a county road intersection to withstand the passage of a derrick crane with a 250-ton lifting capacity. First, dump trucks lay a thick bedding of dirt on the road for cushioning. Then huge steel plates are positioned like tracks atop the dirt. Only then can the crane be pulled down the road.

Tower sections and blades for the Scurry County Wind Farm lie in nearby fields as other cranes prepare to erect the equivalent of 30-story structures. “It’s a great day for flying steel,” said one of my guides. That’s wind construction slang meaning the wind is calm enough for a crane operator and ground crew to heft a multi-ton blade into place some 200 feet above the ground.

I see workers, tiny against the span of a single blade, tighten the connections for a lift and signal the crane operator to hoist it over their heads. But I move on before the blade is attached to the tower.

At Snyder Wind Farm, I walk with my head tilted back, taking in the enormousness of these modern-day windmills. In the parking lot are pickups and cars from Nebraska, Utah, Minnesota, Nevada, Oklahoma, Montana and Wyoming, not to mention Texas. Con-

struction is going on all around us.

The place is an ant bed of activity. In one direction, men are digging deep ditches for underground electric lines. It’s not a matter of aesthetics but rather of necessity. Above-ground lines would impede the transport of wind turbine parts. In the distance, steel is flying.

Riding in a pickup with wind farm employee Austin Hill of nearby Merkel, we weave around completed windmills standing smack dab in the middle of a luxuriant cotton field. It’s surprisingly quiet. The wind at 8 mph is not strong enough to produce electricity. Instead, the tower’s three blades are circling casually in the breeze. The movement so high above me is somewhat deceptive. The tips of the 300-foot-diameter wingspread are moving at about 100 mph. Even standing directly under the rotating blades, the only sound is a rhythmic, muffled “swoosh.”

Windfall for West Texas

West Texas institutions and individuals are reaping rewards from the boom. The Trent school system has been able to afford a new school building and a stadium with artificial turf for its six-man football team. Individual landowners are also enjoying a new steady source of lease income.

Carl Williams, president of the Big Country Electric Cooperative board of directors, has allowed six turbines to be constructed on the high-elevation plains where he raises cattle and cotton. One of the turbines is 300 yards from his back door. From his driveway, it looks as if it is looming over the Williamses’ one-story house. The windmill stands about 300 feet tall. Each blade reaches about 145 feet. And when the wind is blowing, the hub (nose cone) can revolve about 21 times per minute. Typically, the turbines automatically shut off when the wind blows above 45 miles per hour.

“Outside the house, I can hear the wind swishing when the blades are turning. But I can’t when I’m inside,” Williams said. “You better appreciate the sound when you know you’re getting an income from it.”

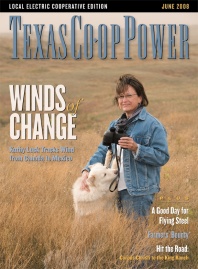

It took seven years to get the turbines up and running and the quarterly wind royalties churning. (See our accompanying story, “Winds of Change” on page 6, for details of property leasing.)

“The wind projects put a little money in circulation,” said Williams with a touch of West Texas understatement. “They add a lot to the property tax base, particularly for local public schools.”

Cliff Everett of Roscoe, who has wind turbines on his property, was a little more enthusiastic when he recently told National Public Radio, “Who would have thought we could sell something we don’t even own!”

Working for the wind

The Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) grid, which covers about 85 percent of Texas, currently has a guaranteed transmission capacity for only about 3,400 MW of power at any one time from low-population West Texas to the high-population centers of the state, according to Bob Kahn, ERCOT’s president and CEO. Online wind farms have a capacity to produce 5,000 MW. Many more transmission lines must be built, providing even more construction jobs.

Jobs of all kinds are available. Take, for example, 87-year-old Royce Smith, a member of Coleman County Electric Cooperative, who has gotten into the act driving an escort truck behind the steel tower sections of wind turbines. “I love traveling. I’ve enjoyed every minute of it,” says Smith, who had to qualify for a commercial driver’s license and take out $1 million of liability insurance. His wife wants to join the escort business when she retires. “I bought her a pickup for Christmas and got it rigged up with emergency lights,” Smith said.

The city of Coleman, headquarters of the co-op, is home to several fabricating companies including the Wind Clean Corporation, which employs 130 people. Wind Clean provides coating systems for the steel sections that make up a wind tower. It also assembles internal components. Across the state, other fabrication companies are making parts for the industry, creating at least a temporary surge in construction jobs.

Co-op involvement

Fredda Buckner, general manager of Big Country Electric Cooperative based in Roby, said she began getting calls from wind farm developers in her area about four years ago.

How many are in Big Country territory now? She ticked off Snyder Wind Farm, Lone Star Wind Farm, Post Wind Farm, Scurry County Wind Farm, Scurry County No. 2 Wind Farm, Brazos Wind Farm, plus Hackberry Wind Farm, Pyron Wind Farm and Inadale Wind Farm under construction—all of them signed up for Big Country electric service.

Transmitting the wind energy to where it is most in demand will cause great technical challenges, but as Buckner said, “The business is so good for the area, I can’t say anything bad about it.”

At this juncture, nearby distribution co-ops are not receiving wind-generated electricity from the farms in their own backyards. However, Bob Bryant, general manager of the Golden Spread Electric Cooperative, a generation and transmission co-op based in Amarillo, says the company plans to bulk purchase at least some wind power for its members in the future.

Electricity from most of the new wind farms is destined for Dallas/Fort Worth, Houston and San Antonio/ Austin. West Texas remains transmission constrained. We’ll explain what that means in a story about the Texas power grids in August.

——————–

Kaye Northcott is editor of Texas Co-op Power.