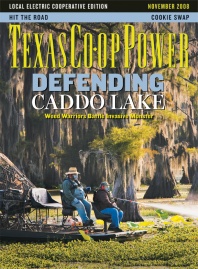

Editor’s note: Marshall native Jack Canson moved back to his hometown in 1993 to be close to a great treasure of his youth, Caddo Lake. He soon discovered that people never run short of battles to protect the lake. In May 2006, a new threat emerged—this time from the tea-colored waters of the lake itself. A prolific fern named giant salvinia quickly began spreading throughout its fragile ecosystem. Photos accompanying this article depict some of the efforts by Canson and other “Weed Warriors” as they confront and struggle to contain a lake-eating monster.

It has no teeth, claws, scales or fur. It’s not a mammal or a reptile that rips victims apart. Rather, it kills by slowly and cruelly suffocating everything in its path. In addition to Caddo Lake, it lurks in many other lakes, streams and wetlands throughout the South. Toledo Bend Reservoir, Sam Rayburn Reservoir, B.A. Steinhagen Lake, Center City Lake, Lake Texana, Sheldon Lake, Lake Conroe, Brandy Branch Reservoir—all are fighting this new menace in Texas. It has reached Lake Palestine, near Tyler, and is slowly heading west.

Its victims are everything and everyone who depend on water. The water that plants and animals need for survival. The water in which fish swim and reproduce. The water that power plants and other industries need. The water we drink.

This water-eating monster is a plant. And of all the plants on earth that it could be, this one is what we normally consider the most innocuous of plants. It is, of all things, a fern.

Caddo Lake, straddling the border between northeast Texas and northwestern Louisiana, has survived many threats in its history, but today, Texas’ only natural lake faces its greatest challenge: a rootless, floating, aquatic fern no larger than a child’s fist. And all hands are pitching in to try to control it.

Aptly named, Salvinia molesta, or giant salvinia, slowly is becoming recognized in the United States as potentially the most destructive natural calamity ever to threaten southern water bodies. In warm, still water, the free-floating plant can reproduce explosively. One acre can become two in one week. Plants combine into dense chains and form mats that can carpet entire lakes, large and small. Giant salvinia is most commonly spread by hitching a ride on boat trailers—humans are actually moving it west.

A Place of Wonder

Caddo is a place of myth and legend. It’s a place where one can be so intensely surrounded by natural wonder that an outdoor adventure morphs into a journey of the spirit. Its spooky bayous twist through hazy swamps. Shadowy birds zigzag between curtains of Spanish moss. Red-eared turtles slide off snags into tea-colored water. A profound sense of a primeval and distant past drifts along the backwater sloughs like fog.

If you know Caddo Lake, or even if you’ve only visited here, you feel like it belongs to you—and you belong to it. And because of that emotional connection to this mysterious place—and its ecological, historical and cultural richness—residents, in a spirit of cooperation, were among the first to respond to the emergency.

Weed Warriors to the Rescue

On the Texas side of Caddo Lake, what funding has been obtained supports locally managed programs already initiated by Caddo Lake residents instead of adding additional state personnel and equipment. Now, area political leaders are stepping up to the plate, trying to come up with money for a serious fight against the giant salvinia that has taken over an estimated 1,600 acres of the 27,472-acre Caddo Lake.

When giant salvinia was first discovered in Jeems Bayou on the Louisiana side of Caddo Lake in May 2006, concerned residents from all around the lake gathered to press the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) to learn what they planned to do about it. It became apparent early on that neither agency had the money, manpower or equipment to do much of anything. This was not a failure of the dedicated agency biologists and field technicians. Federal funding to control invasive aquatic plants is almost non-existent, and when giant salvinia arrived, neither state’s legislature had appropriated the funding that even a modest control effort requires.

With the help of the Caddo Lake Institute, a nonprofit scientific and educational foundation, locals on the Texas side got organized, consulted experts and experimented. One experiment was a burn test with a flame-throwing liquid propane torch that hit the plants with 2,000-degree heat. The heat-treated samples turned black as Sunday shoes and looked as dead as last week’s road kill. But 24 hours later, little green buds began to emerge. Within seven days, the burned-out plants were completely covered with new giant salvinia plants that grew out of the blackened mass.

“I’ve never seen anything that could spring back from that kind of heat,” said Mike Welch, who usually uses his propane tanks to sanitize chicken farms. “This is one tough plant to kill.”

Giant salvinia, a native of Brazil, reproduces by vegetative fragmentation. If herbicide or freezing temperatures damage 90 percent of the plant, new plants grow out of the remaining part. Chop a bunch of it up, and you’ve just made a zillion new giant salvinia plants.

“It’s nearly the perfect pest as an aquatic plant goes,” said Jeff Sibley, a fisheries biologist supervisor for LDWF.

In Brazil, giant salvinia is held in check by seasonal drought and the cyrtobagous weevil, a tiny insect that eats on its leaves and deposits eggs in the cavities. In some climates in the world, the weevil can be fairly effective. It won’t eradicate the plants, but holds them back. There is skepticism that in the climate zone at Caddo Lake weevils could ever damage giant salvinia faster than it grows.

Randy Westbrooks, invasive species prevention specialist at the U.S. Geo- logical Survey National Wetlands Research Center in Whiteville, North Carolina, cautions against placing too much faith in the weevil.

Based on nearly a decade’s effort by federal and state officials to control giant salvinia with salvinia weevils in the Toledo Bend Reservoir on the border of East Texas and Louisiana, Westbrooks said, “It is questionable whether the weevils would be any more effective in Caddo Lake—which is farther north.”

The farther south the better for the weevils, Westbrooks said, explaining that they are more adapted to warmer areas. Overall, it appears that giant salvinia has much more tolerance to hot and cold weather, shade and sun than does the weevil, he said.

The plant has thrived at Toledo Bend. Due to high water levels during summer 2004 that contributed to the growth of giant salvinia, fall aerial surveys indicated that there were more than 3,000 acres of giant salvinia reservoir-wide despite a vigorous herbicide spray program. In spring 2005, about 5,000 acres were documented reservoir-wide.

On the Louisiana side of Caddo Lake, LDWF officials are putting a lot of faith in weevils … and they’re praying. On the Texas side, the Cypress Valley Navigation District has refurbished a TPWD airboat and plans a major herbicide program. They’re spraying and praying. Last year, they raised more than $60,000 from local governments and industries, and volunteers helped build a 2-mile-long net-and-post fence across the water from the north to the south shore. This slowed the westward advance of the monster into the vulnerable shallow waters on the Texas side. Unfortunately, nature dealt the fence a major beating, and it has since been torn down.

It is a Class C misdemeanor punishable by a fine of up to $500 per plant to possess or transport giant salvinia in Texas, so TPWD conducted classes to train and license more than 50 volunteer “Weed Warriors” to net and destroy giant salvinia from the Texas side.

The Texas giant salvinia fighters have attracted considerable attention, which has helped them obtain support from elected officials. The Texas Legislature, pushed by State Sen. Kevin Eltife and Reps. Stephen Frost and Bryan Hughes, appropriated $240,000 to Texas Parks and Wildlife for the next two years to help fight invasive aquatics at Caddo Lake. U.S. Rep. Louie Gohmert, a Republican congressman whose northeast Texas district includes the Texas side of Caddo Lake, and U.S. Sens. Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas and Mary Landrieu of Louisiana are prodding federal agencies and their colleagues, trying to awaken them to this looming catastrophe.

Although the money already obtained is not insignificant, experts believe it is going to take more, much more, before control efforts destroy giant salvinia faster than it grows.

Giant salvinia and other invasive aquatic plants affect the economy as well as the ecology of Caddo Lake. By depleting dissolved oxygen and obscuring sunlight from vital spawning areas, giant salvinia poses a serious threat to Caddo’s vaunted reputation for some of the best fishing in the South.

Many residents, such as George “Shorty” Hood, earn their living providing bait, ice, fish-cleaning and guide services to visiting anglers.

A weed-smothered Caddo would also harm bed and breakfast and other lodging owners, such as Joann Hodges. Hodges operates seven lake cottages in Uncertain.

At nearby Lake Bistineau in Louisiana, a massive giant salvinia infestation has brought tourism to a halt, emptying RV parks, marinas and dining establishments.

On July 15, officials began to draw down Lake Bistineau, hoping to minimize the amount of giant salvinia that escapes downstream while maximizing the amount that gets stranded and dies. The lake will continue to be “de-watered” at the rate of two to three inches a day through January, when the gates will be closed and the lake will be allowed to refill.

Many lakes need help fighting giant salvinia. There will be many more soon. People at Caddo will be sure that whatever help arrives, the lake gets its share.

A common refrain among Caddo Lake lovers fighting the giant salvinia monster can be heard in the voice of Mike Turner, a lifelong lake resident who operates a boat repair shop in Uncertain and is one of the Weed Warriors spraying or removing giant salvinia almost daily.

“If we don’t care enough about Caddo Lake to do what it takes to stop it here,” Turner says, “where else on earth would we care enough?”

——————–

Jack Canson, a native of Marshall, is a former screenwriter. He is currently doing a documentary on Caddo Lake.

Go to www.caddolakenews.org or www.caddolakeinstitute.us for additional information.