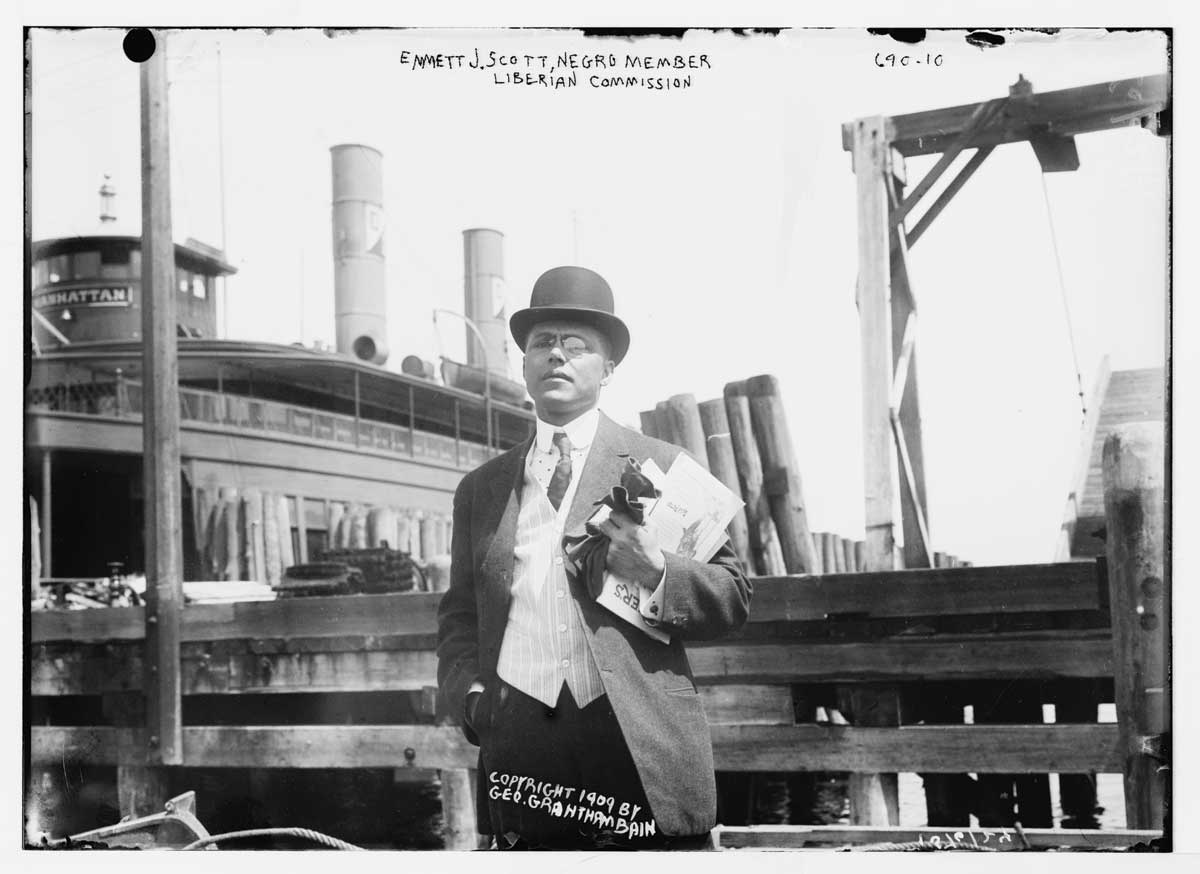

Emmett Jay Scott, a Texan born 150 years ago this month, established a remarkable record of achievement, mostly out of the public eye. His long life was so full that a biography of the writer, educator, government official and right-hand man to Booker T. Washington took author Maceo Dailey some 50 years to complete.

Scott’s name doesn’t come up often in tributes during Black History Month, yet decades ago his significant championing of African American rights warranted a commentary in The Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper that potently pegged him as a quiet leader.

“He exhorts an influence upon public men which is unique and inimitable; but the basis of his influence is subtle, intangible and difficult to define. … He holds no public office, does not manipulate any political organization, nor does he arouse public emotion by any spectacular appeal. He does not possess great wealth nor profess great learning; he carries no votes in his vest pocket. But nevertheless his counsel is sought and heeded by men who do things and want things done.”

Those words, published in 1936, were an unlikely testimonial to a man born February 13, 1873, to formerly enslaved people and raised in the Freedmen’s Town section of Houston. Scott attended Wiley College in Marshall from 1887 to 1890. (He dropped out to give other members of his family the same educational opportunities he had.)

To help fund his education, he carried mail, chopped wood, fed hogs and kept books for the college’s president. Back home, he worked his way up from janitor to journalist at The Houston Post. In the 1890s, Scott co-founded and edited The Texas Freeman, one of the first Black newspapers west of the Mississippi.

The biography by Dailey, Emmett J. Scott: Power Broker of the Tuskegee Machine, describing Scott as a Renaissance man, scholar and political fixer, is in the works at Texas Tech University Press.

Scott’s influence grew beyond Texas when he met Washington for the first time. Washington, the distinguished educator and foremost Black leader at the turn of the 20th century, presented the commencement address at what is now Prairie View A&M University in 1897, and Scott was there. Washington recruited the Texan to assist with his work at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

For the next 18 years—until Washington’s death in 1915—Scott served as his closest confidant, adviser, ghostwriter and unyielding champion.

Washington and Scott sought to produce a film based on Washington’s autobiography. That project ended with Washington’s death, but Scott pursued another film project—a counter to the racist stereotypes presented in D.W. Griffith’s 1915 blockbuster epic The Birth of a Nation.

Scott envisioned a film that would present “the true story of the Negro—his life in Africa, his enslavement, his freedom, his achievements—together with his past, present and future relations with his white neighbor. It will bring close the future in which the races—all races—will see each other as they are.”

The project soon morphed into a three-hour epic rebuttal, Birth of a Race. Sadly, the version that eventually was made—a lone print of which survives in the Library of Congress—bore no relation to Scott’s vision.

But Scott’s focus soon changed as the U.S. moved closer to war. Woodrow Wilson was elected president, and Scott was named to the War Department in 1917. Among his duties were improving the morale of Black troops and investigating racial incidents and charges of unfair treatment.

Though the nearly 400,000 Black soldiers who went overseas faced racism (the Marines banned Black people from enlisting, for example) and many were relegated to support roles, Scott documented their combat heroism in his books Scott’s Official History of the American Negro in the World War and The True Story of the Harlem Hellfighters in World War I.

Some 15 years after the war, Scott addressed Black veterans, decrying the ingratitude of the nation for their sacrifices.

“I have always contended that a country worth fighting for is worth living for,” Scott was quoted as saying in the New Journal and Guide, an African American newspaper in Virginia. “At the same time, I have always contended that a man who is brave enough to carry a gun in defense of his country’s honor should be honored with all of the rights and privileges of untrammeled citizenship.”

Noting the exodus of Black southerners that intensified during World War I, Scott wrote Negro Migration During the War. Nearly a half-million African Americans left the South during the Great War, and over the next half-century, participants in the Great Migration swelled to 6 million.

“They left as though they were fleeing some curse,” he wrote, describing the “solemn ceremonies” performed by 147 migrants from Mississippi as they prepared to cross the Ohio River. “These migrants knelt down and prayed; the men stopped their watches and, amid tears of joy, sang the familiar songs of deliverance.”

Scott himself took his family north after the war. From 1919 to 1934, he served as secretary-treasurer and business manager of Howard University in Washington, D.C.

During World War II, he was hired to oversee recruiting by the Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Co. in Chester, Pennsylvania. According to one source, more than half of the company’s 35,000 workers were Black. Sun was reportedly the world’s largest shipyard during the war.

Sun’s shipyard No. 4 was staffed fully by African Americans. Scott emphasized the valuable role that vocational training could play in improving race relations. And he was quoted as saying that Black workers’ accomplishments in the shipyard would help to remove the “doubts and fears regarding the capability of the Negro craftsman.”

Scott advocated for education as one of the strongest tools for lifting his people out of poverty. He later returned to Wiley College and earned a master’s degree, and all five of his children achieved college degrees. He and his wife also raised his five younger sisters, who also earned their degrees.

Elaine Brown, a granddaughter, inherited his passion for racial justice, becoming chairwoman of the revolutionary Black Panther Party.