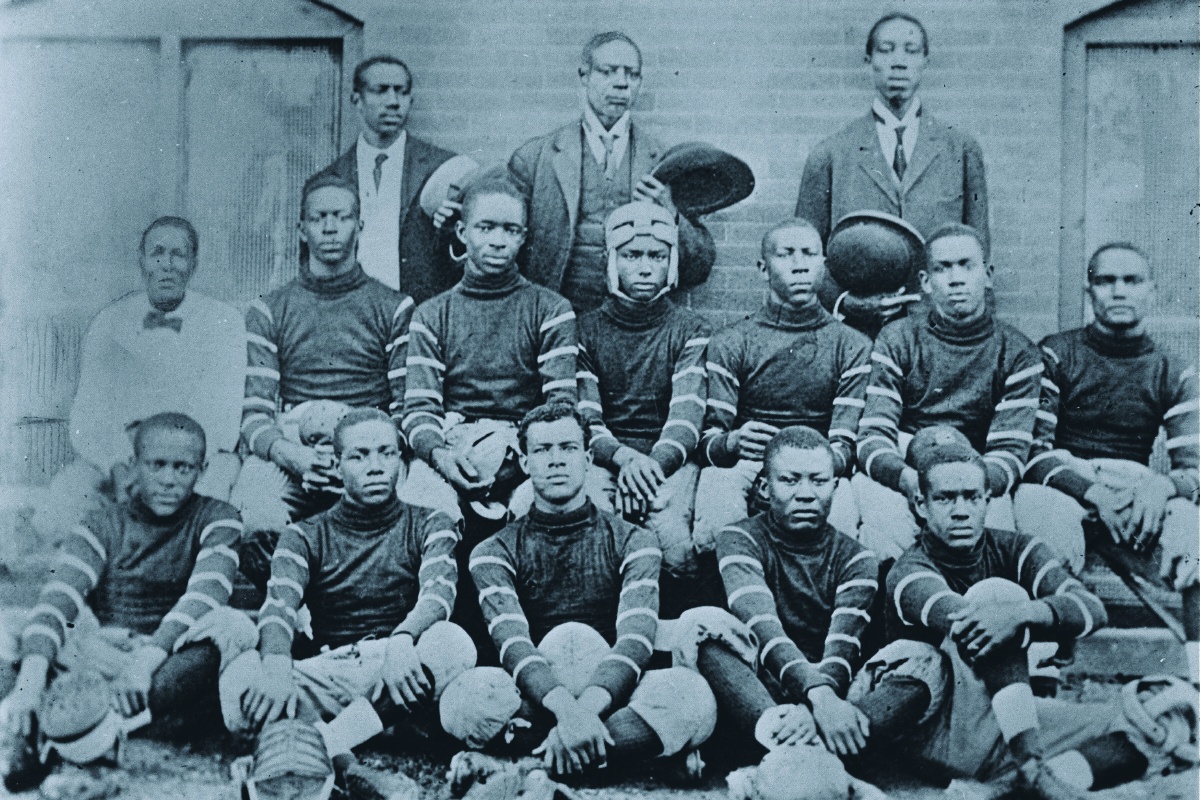

From 1920 to 1970, the Prairie View Interscholastic League served as the governing body for athletic, academic and music competitions for segregated black high schools in Texas. Founded at Prairie View A&M University as the Texas Interscholastic League of Colored Schools, the PVIL mirrored the University Interscholastic League (founded at the University of Texas at Austin), which directed the same activities for the state’s white high schools. From its inception in 1910, the UIL denied membership to African-American schools.

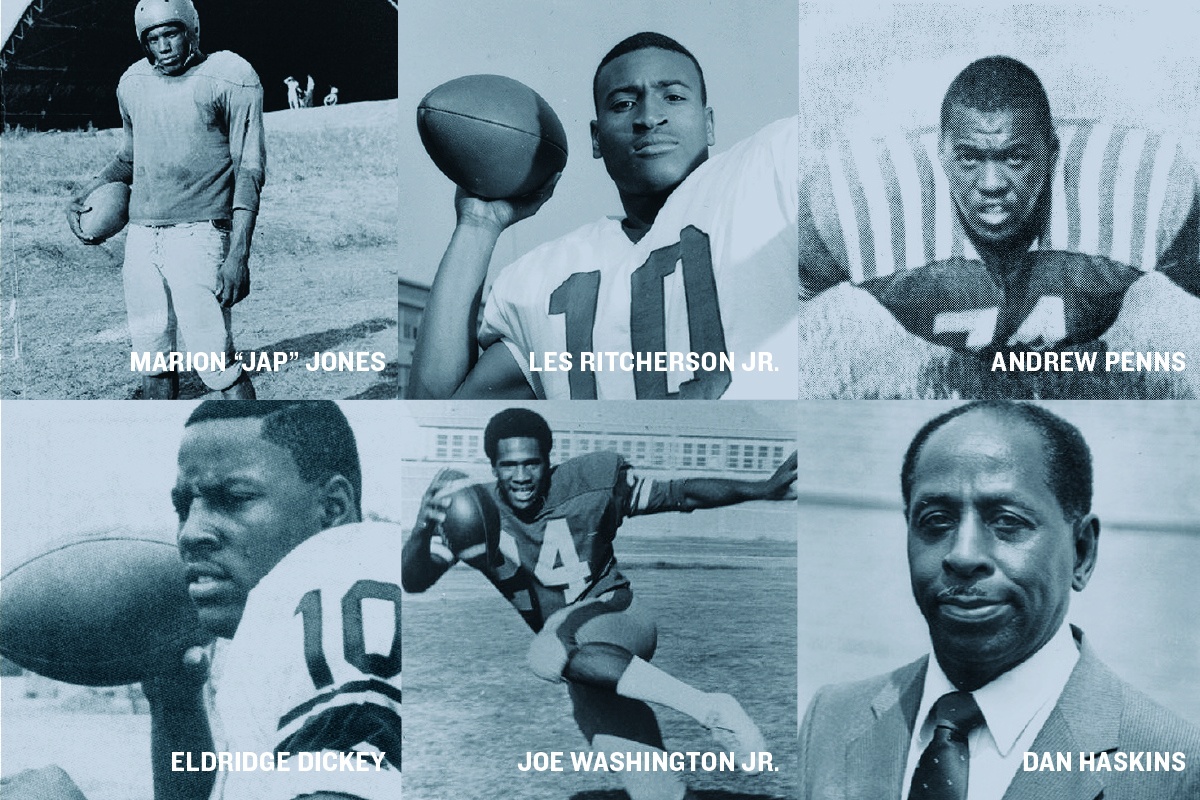

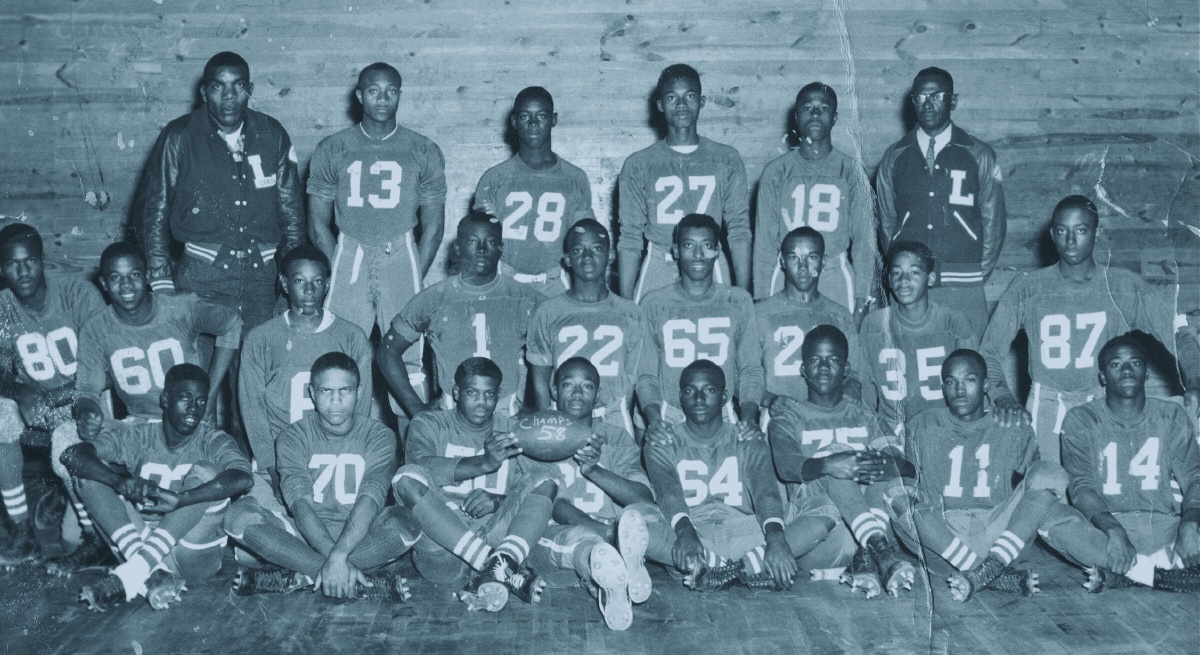

After integration, the two leagues merged in 1967, and the majority of the PVIL’s 500 schools closed. Only eight remain as members of the UIL. White schools played their football games on Friday and Saturday nights; PVIL games were on Wednesday and Thursday nights. Yet the underpublicized PVIL produced a who’s who of high school, college and pro football talent, including Otis Taylor (Houston Worthing High School), Bubba Smith (Beaumont Charlton-Pollard), Jerry LeVias (Beaumont Hebert), Dick “Night Train” Lane (Austin Anderson), “Mean Joe” Greene (Temple Dunbar), Abner Haynes (Dallas Lincoln) and Ken Houston (Lufkin Dunbar). In Houston, from the 1940s to 1960s, the Jack Yates Lions and Phillis Wheatley Wildcats met on Thanksgiving Day in the largest prep school game in the country, drawing standing-room-only crowds that reached 40,000.

In this excerpt from my book, Thursday Night Lights (University of Texas Press, 2017), I write about my motivation for telling the story of black high school football in Texas.

Excerpt

[Jeppesen Stadium in Houston] sat on a 60-acre tract bordered by Holman Street to the north, Cullen Boulevard to the east, Wheeler Avenue to the south, and Scott Street to the west. Scott was a major artery of asphalt potholes connecting the growing black communities from the Third Ward south to Sunnyside. The stadium and its field house were one block east of the all-black high school named after the minister, community leader and former slave, John Henry “Jack” Yates—who was also the first pastor of the first black Baptist church in Houston, Antioch Baptist Church, established in 1866. The crimson-and-gold Jack Yates High School Lions had a perfect home-field advantage and a walking commute to observe competing PVIL teams and even Friday night action.

Alphonse Dotson, a lineman for Yates, talked about those gatherings: “We would go over to Jeppesen and watch the [white] schools play on Friday nights. Hell, we could play with them and play well, hold our own. We would have done well against them, but that they kept us separate was for a different reason. We’d also have some camaraderie with guys from [PVIL schools] across town, might have a fight. But as long as you weren’t courting a girl from somebody else’s neighborhood, you were fine. You wanted to win when you played against them, but you wanted them to do well afterwards.”

The stadium stood as a buffer between the Houston College for Negroes, just getting its start by holding night classes at Yates, to the southwest on Wheeler, and segregated University of Houston, immediately to the northeast on Cullen. By 1947, the College for Negroes had begun developing its own campus, and Wheeler ran through the center of what would become Texas Southern University.

Besides the players and coaches, what I knew about high school football were the Wednesday and Thursday night games I saw at Jeppesen. So I was puzzled the first time I heard the phrase “Friday night lights.” And as I researched this book, I found that I was not alone in that reaction, since most of the former PVIL players and coaches I spoke with around the state agreed the term had little to no meaning for them. Most black high schools in Texas played on nights other than Fridays unless they had their own facility, as only a few did, such as Texarkana Dunbar. Its Buffalo Stadium was located behind Theron Jones Elementary School, and during lunchtime my classmates and I chased one another around the field.

On game nights, I would wander through the gravel-and-red-clay parking lot, look for my parents, and pass visiting players in dirty, sweaty togs kissing their cheerleader girlfriends before boarding buses for the trip home. (I thought that was pretty cool.) White schools had priority for the Friday night use of public stadiums shared with black schools. Asked about Jeppesen Stadium’s use, a stunned former PVIL football player responded as though the place was the PVIL schools’ private domain: “You mean they used that stadium on Friday nights?”

I remember a cold, drizzly December night in 1961 at Jeppesen. I was 12 and sat bundled up next to my dad in the stands as Orsby Crenshaw and the Austin L.C. Anderson Yellow Jackets won a 20-13 contest against Yates for the PVIL Class 4A state championship. Anderson was coached by Raymond Timmons, who that night bested the great Andrew “Pat” Patterson, whose team had come into the game undefeated. It would be the last of four state titles for the Yellow Jackets, and the only state championship game I ever witnessed.

That was my high school football experience growing up, attending segregated schools in the 1960s.

It had nothing to do with Friday night lights.

More to the point, as one PVIL alum put it, “Friday night lights? That’s white folks.”

This book is about “black folks” who coached and played high school football behind the veil of segregation in Texas for half a century, 1920–1970, as members of the all-black Prairie View Interscholastic League, whose games were played primarily on Wednesday and Thursday nights in most towns, Tuesdays in others, some on Saturdays, but rarely on prime-time Friday nights, when games for white schools were played. The book’s title, Thursday Night Lights, is not just a riff on “Friday night lights” but also identifies a defining reality of high school football games played in racially charged times when even the midweek scheduling of games for black teams carried a “less than” feel.

The PVIL’s genesis was as the Texas Interscholastic League of Colored Schools, organized three years after white policemen and citizens’ mistreatment of black soldiers from the 24th U.S. Infantry led to the horror—17 people shot and killed—of the Camp Logan mutiny and Houston riot of 1917. The league folded in 1970, one year after the University of Texas fielded its last all-white football team.

Emotionally, I have been writing this book since adolescence and the first time I saw PVIL greatness up close and personal in David Lattin and Otis Taylor, Worthing and Sunnyside heroes. I remember a profusely sweating “Big Daddy D” jogging coolly in his own world around the school track on a hot spring day to whatever groovy tunes were streaming through his transistor radio earplug, and Taylor, back in the ’hood, sitting at the wheel of his brand-new candy-apple-red Thunderbird convertible as the fellas in Reedwood took a break from playing basketball to crowd around and admire the vehicle, which he bought after he signed his rookie contract with the Kansas City Chiefs. Both guys would show up on the big stage. Lattin threw down a monster dunk to set the tone for Texas Western’s destruction of Adolph Rupp’s Kentucky Wildcats in the 1966 NCAA championship game, an upset for the ages that is credited with ushering in the recruitment of more blacks by previously all-white programs. Taylor, a strong but graceful receiver, was among the cadre of players from historically black colleges who helped bring the American Football League to life. In Super Bowl IV, Taylor, a prototypical big, fast receiver, caught a short pass from Len Dawson, broke tackles by cornerback Earsell Mackbee and safety Karl Kassulke, and high-stepped down the right sideline to the end zone, securing the Chiefs’ 23-7 upset win over Minnesota.

Lattin and Taylor were local heroes, and I followed their careers, but I had a vested interest in following other PVIL football players from the Houston area, too, as a fan and then as a sportswriter. I read team depth charts and player bios, noted high school affiliations, and had flashbacks of sitting in the stands at Jeppesen while watching some of those teams play. Thursday Night Lights reveals the PVIL quilt that was a patchwork of athletic, academic and social achievements pieced together for a black community striving to succeed, to take care of its own despite the era’s racism. For me, its history became a simmering narrative bred in familiarity, born from segregation.

I had to tell this story.

Michael Hurd is director of the Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture at Prairie View A&M University. He is a Houston native and former sportswriter for the Austin American-Statesman, USA Today and Yahoo Sports.