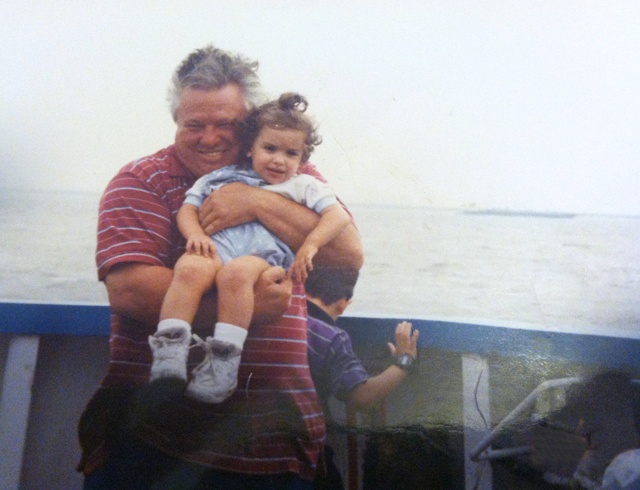

As a little girl, I envisioned my grandpa being 10 feet tall with strong arms that could lift me with ease and a belly so big he could be Santa Claus. But only part of my memory was accurate. My grandfather was a big man, but no giant. His strength and build came from 30 years of loading, lifting and hauling products on and off of ships at the waterfront, as I have always called it—the Port of Houston to most.

Grandpa spent his entire working life on the waterfront and says he doesn’t think his experiences would interest anybody. He’s firm in his humility, but a granddaughter’s curiosity can soften a soul, and I was able to coax free some stories of his job. He agreed to tell me about his life on the ships but asked that I not make a big deal out of it or put his name in a magazine. He loves his granddaughter, but he’s still just Grandpa.

Born in 1942 and the son of a U.S. Navy sailor, Grandpa traveled a lot as a child from Hawaii to California to Detroit and ended up back in Houston. He started his career as a longshoreman in 1960 as a 140-pound 18-year-old boy who had to give up amateur boxing and was tired of delivering medicine on a bicycle for the local drug store.

“I was a fair boxer,” he says, which is just like my grandpa, always modest. He actually won 20 out of 23 fights, but his skin “cut too easy,” he says, and he couldn’t continue. “My stepmother’s brother was working on the waterfront—he had been there 20 years—and he offered to get me on. So I went down there, and he got me on, but man, it was terrible.”

His first job was unloading sacks of drilling mud from ships, and he says he learned quickly how tough this kind of job would be.

“For about an hour I was OK,” he says. “I could pick up the 110-pound bags of drilling mud, and I had to carry them back about 30 to 40 feet and stack them. About that second hour, I was burnt out. I started dropping the bags and couldn’t pick them back up, so I went up the ladder and told the boss, ‘I’m done.’ ”

The next day, his job was lifting 140-pound bags of coffee and stacking them above his head. After about an hour, he was done again. “That went on for about two weeks, and then I finally started getting tough and could handle it.”

On the waterfront, longshoremen were hired out every day to whichever foreman or ship needed workers for a job unloading or loading. The men would stand in specified areas in the union hall based on seniority, holding their pay cards, and the foreman would come by and take their cards if they agreed to the job.

As he got stronger, he could handle more and tougher jobs, which was necessary on the ships if he wanted to earn more money.

“Then I would just work every job,” he says. “Each job was new. It’s always a different ship. Sometimes I’d work rice, sometimes 140-pound bags of flour in burlap bags. I built myself up and I was up to 180-200 pounds before long, and there wasn’t a job I couldn’t handle.”

He started out making $3.01 an hour in the 1960s. The salary was pretty good at the time, he says, but it came with a good amount of risk.

“They were all dangerous,” he says. “The loads would come in swinging, and a sack might fall off a load and there you are, but the most dangerous jobs were the pipe jobs.”

Steel pipes were 10 to 12 inches in diameter and could be 10 to 12 feet long. “We picked up a load of pipe one time and it got caught up and broke the wires,” he says. “The whole load came down, and I was just standing there watching.”

Grandpa remembers running and jumping into a hole off to the side on the deck of the ship, diving down about 30 feet. He chuckles at the memory of the other guys trying to pull him out. “It took them awhile to get me out, but I didn’t have no pipe on me.”

My mom, Kada Lamas, remembers my grandpa’s friends much like I remembered my grandpa: giant, burly men. She also remembers watching in awe as they came in from the ships to eat and sleep before heading out again.

“I remember one that they called John the Baptist. He must have been 6-foot-5, and he was a huge man,” she says. “But he was so sweet. My mom would make beans and rice and all these huge men would come in and eat everything.”

Grandpa saw many changes on the Houston Ship Channel, including the desegregation of the union halls, implementation of container cargo and the growth of the Houston shipping industry.

“When I first started, there weren’t any containers, and the containers really took over a lot of stuff,” he says. “There were still ships that you had to unload bags, but the main ships would come in to Barbours Cut.”

Barbours Cut is part of the port at the opening of the channel. A crane was stationed there to handle the containers early on, he says. When he first started, a lot of ships were the victory ships from World War II that had been converted for commercial cargo. By the time he retired in 1999, there were all kinds of container ships that could hold 2,000 to 3,000 containers.

Being a longshoreman is all my grandpa ever knew, and although it was rigorous work, he appreciated the opportunities it afforded him. “I was extremely blessed to get this job because I had an eighth-grade education,” he says.

Twenty years later, while he’s not as muscular as he once was, I still see my grandpa as the strongest man I’ve ever known.

——————–

Brittany Lamas is a former editorial intern.