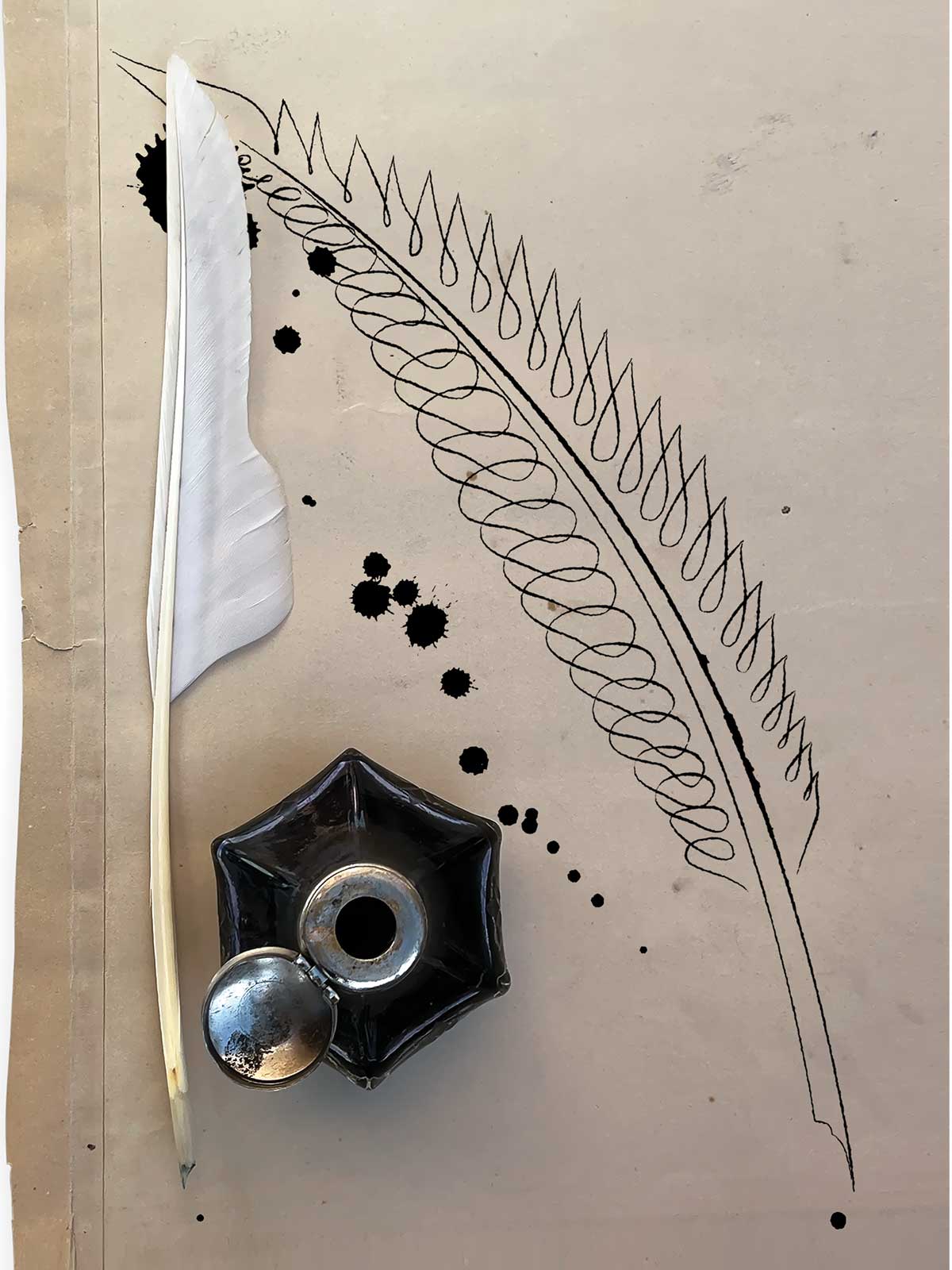

Long before Bic pens began to roll off assembly lines in the 1950s, frontier Texans drew up their official documents and signed their names using a quill pen and iron gall ink.

When Stephen F. Austin signed the land grant from the Spanish government in 1824 allowing 300 families to resettle in the Texas territory, iron gall ink was likely his only option. It was used for the constitution of the Republic of Texas, the Texas Declaration of Independence and many cherished family letters that have been passed down for generations.

Before iron gall, inks were made from soot collected from burning plant materials or bones mixed with water and glue, but these carbon-based inks were easy to smudge or remove.

Oak trees produce nutlike growths called galls as a reaction to wasps depositing eggs beneath the bark. The tree encapsulates the eggs, and after wasps emerge, the insects bore a hole in the gall and fly off.

Ink makers crushed dried galls with a mortar and pestle, although a hammer worked as well. They then soaked the powder in a small jar of rainwater along with a handful of rusty nails. Placed in a sunny spot for 10 days or so, the tannic acid from the oak galls would react with the rust, making a light brown- or sepia-colored ink that turns black in a matter of hours when applied to paper. Adding a bit of gum arabic—basically hardened tree sap—made the ink flow better.

Since iron gall ink is not easily removed, it was the obvious choice for record keeping in the Western Hemisphere for hundreds of years, from the fourth century into the 20th century. Monks in medieval monasteries used iron gall to copy manuscripts, and Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks and the musical scores of Johann Sebastian Bach were executed in iron gall. It was a popular drawing ink in the 15th century because of its rich, velvety tone and was used for drawings by Rembrandt and Vincent Van Gogh.

Some people still use the ink today, and you can buy it online if you don’t want to make your own.

But there’s a reason iron gall wasn’t used to fill your Bic: The ingredients make it inherently unstable. It often fades and corrodes over time, weakening paper—especially where it is heavily applied—and can eventually cause discoloration, brittleness, cracks and holes. Humidity and light are its worst enemies.

Storage conditions for historical documents and the amount of use they are subjected to can also affect their condition, which can range from a slight browning of the ink itself to corroded paper so full of holes that it resembles lace.

“Not all iron gall ink documents show severe damage,” says Heather Hamilton, a conservator at the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. “Iron gall ink formulations differed, and some were more stable than others. Also, some papers were more prone to becoming damaged by the inks— thin papers, for example.”

Hamilton says past display practices have caused the iron gall ink to fade on some treasured documents, including the William B. Travis letter and the original Texas Declaration of Independence.

She says the TSLAC now follows conservation best practices that better prevent fading, including carefully monitoring light exposure.

When irreplaceable Texas historical documents written in iron gall ink travel, as was the case when the Travis letter was displayed at the Alamo in 2013, they are packed carefully to reduce vibration during transport. To protect the fragile letter from variations in temperature, humidity and light, it was enclosed in a Mylar sleeve and mounted between sheets of high-quality, anti-reflective plexiglass in the conservation laboratory of the Texas State Library and Archives in Austin.

Just as natural dyes, like that extracted from the tiny cochineal bug for centuries to make bright red coloring for food and clothing, were eventually replaced by synthetics, iron gall ink has given way to synthetic inks made using dye suspended in a mixture of solvents and fatty acids.

Are they better than iron gall? Only time will tell.