Carmadillo,” “Bad Taste BBQ” and the “Mad Cad” may not excel at fuel efficiency.

“But they bring more smiles per mile,” says Noah Edmundson, director of Houston’s Art Car Museum—aka the Garage Mahal.

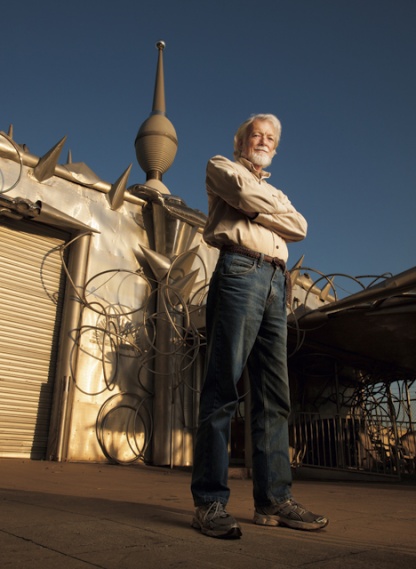

I get an inkling this is no ordinary shrine when I park my Camry next to “Spoonazoid,” a reptilian vehicular creature with hydraulic arms and jaws covered by scales crafted from about 6,000 stainless steel spoons—among dozens of outlandish inventions by Mark “Scrapdaddy” Bradford, guru of Houston car artists.

There’s no mistaking you’re at the right place, thanks to Californian David Best’s oversized scrap metal and chrome exterior, with fenders, bumpers, grilles, taillights and other car parts providing a garage-like motif.

Inside, up to eight elaborately designed vehicles—built from VW bugs, Caddies, unicycles, golf carts, trucks and whatever else captures the imagination—are displayed along with paintings, sculptures and other artwork.

Exhibitions change quarterly, and part of the fun is that you never know what you’ll encounter at the no-fee museum. Car artists represented can range from Bradford, Best and Californian Larry Fuente, all acclaimed nationally, to students participating in college or high school projects. Some creations make social, political or religious statements; others represent pure whimsy. “I just like to do goofy things to cars,” Edmundson concedes.

Displays during my first stop included “Cigs Kill,” a Nash Statesman body covered with tobacco leaves attached to a 1978 Lincoln chassis; a Craftsman riding lawnmower remade into a popcorn cart by 11-year-old Houstonian Harry “Bruiser” Goldberg; and Edmundson’s miniature pedal car labeled the “Dragster” and driven by a skeleton.

On another foray, the prized attraction was “Earth, Wind, Fire (and Water),” created by Rebecca Bass and her students at Houston’s Jefferson Davis High School, who renovated a 1996 Saturn station wagon using mixed media, jewelry, spray foam, mirror pieces and wood. The car, which has its own computer system, includes a working waterfall that flows into a pond at the rear, a fog machine rising from the roof, a fire-breathing phoenix, moving arms and other robotic features plus Earth, Wind and Fire re-creations with their instruments. It’s little wonder this beauty—the 27th art car made by Bass, many with her students’ help—was among the biggest winners at the city’s prestigious Art Car Parade last spring.

On my second visit, “Spoonazoid” had disappeared—but only temporarily, according to museum curator Jim Hatchett. “It’s in our warehouse, but ‘Spoonazoid’ will be back,” Hatchett says.

Some cars are part of the museum’s permanent collection and are rotated as space allows; others are donated, including parade-winners. “Most people are happy to show their work,” Hatchett says. “If nothing else, it keeps them from paying a few months’ storage on them.”

Otherwise, Edmundson jokes, “Some cars go to the scrapyard once the parade is over—if they can make it that far. Or people use them as a personal vehicle.”

Plenty of gems survive: Ever seen a 1972 Honda motorcycle frame supporting a giant red stiletto heel? A 1999 Toyota pickup rebuilt as a cockroach? A 7-foot-tall plastic foam rabbit—complete with fur and sharp teeth—appropriately atop a 1981 Volkswagen Rabbit and holding a basket filled with Easter eggs? They’ve all taken their turn in the spotlight here. Videos in one gallery showcase their brilliance.

While art cars are the signature attraction, the bulk of most exhibitions at the Art Car Museum involves more traditional art and photographs. Edmundson suggests the combination is understandable: “We’re trying to take art cars to the fine art level,” he says, then laughs. “And I suppose we’re taking fine art to the art car level.”

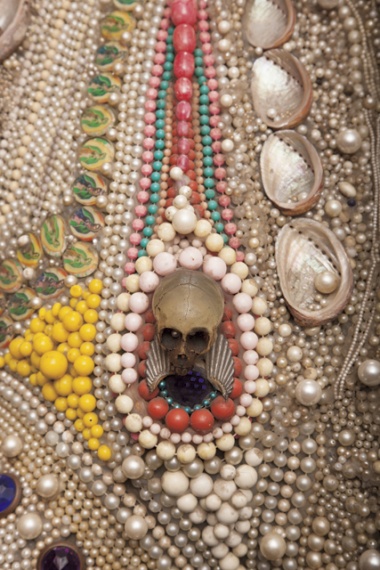

Inspiration for the museum, which opened in 1998, came from longtime arts community leaders James and Ann Harithas. James previously was director of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, director at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and currently directs Houston’s Station Museum of Contemporary Art. Ann, a prolific artist, curated a show (“Collision”) at Houston’s Lawndale Art Center that introduced Fuente’s “Mad Cad”—a one-of-a-kind masterpiece with stylized flamingos, bowling trophies, dolls, beads, teddy bears, mannequins and countless other ornamentation.

“When people saw what Larry did with that car,” Edmundson says, “we thought, ‘The sky’s the limit.’ ”

The “Mad Cad,” since shown at museums nationwide, is largely credited for the debut four years later of an Art Car Parade with 11 vehicles and 2,000 onlookers. The event, conducted by the city’s Orange Show Center for Visionary Art, now attracts 300,000 spectators and entries from 23 states, Canada and Mexico. Scheduled for May 11 next year, it has spawned similar endeavors worldwide: “A lady from England came here, went back and started a parade in London,” Edmundson says. “I attended one in France.”

The museum expands on the theme—with Fuente returning to present cars that include “Rex the Rabbit,” whose construction is a highlight of videos.

While the Harithases remain museum benefactors, chances are you’ll encounter one or more of four staff members during your visit—Edmundson, Hatchett, assistant director Mary Forbes or assistant curator Alicia Duplan. All are artists and have built art cars; they’ve worked together for three or more years; and part of the fun is asking them about their favorite cars and personalities.

Though car artistry isn’t new, its popularity escalated in the 1980s thanks to “a bunch of poor art students bar-hopping and decorating our cars,” Edmundson says. No doubt that’s a shred of truth, but this is a serious pursuit for many professionals—including some who couldn’t find other venues.

“They put their art on cars, and it became a rolling gallery,” Hatchett says.

As Edmundson says, “There are no rules. All you need is a car and an idea. One person did the Virgin of Guadalupe out of license plates. A ‘Go Van Gogh’ car was decorated with Van Gogh paintings. One man from Arizona covered his car with dolls, each decorated differently. It was a wild, wild car. But when he drove it to Houston for the parade, I think he had to sell some dolls to pay for gas.”

Edmundson, a multiple parade winner, and fellow Houstonian Paul Kittleson were inspired to create “Bad Taste BBQ” in 1996, Edmundson says, “because there was never anything to eat during the parade. So we found this Volkswagen, where the engine is in the back and the trunk in front, and we converted the front of the car into a barbecue pit. We smoked turkey, chicken and goat along the way, and after the parade we’d eat everything we smoked.”

Duplan’s first car, “Cleanliness is Next to Godliness,” used detergent boxes to make religious crosses in 1993. A self-described environmental artist, Duplan says, “I went to laundromats all over town and raided their trash cans. I only got kicked out of a couple.”

Duplan’s favorites by other artists include a vehicle designed to represent the Exxon Valdez tanker from which “oil” spilled onto streets during the parade. “Just when you thought that was the end of it, from around the corner came men in black suits carrying briefcases, handing out fake $50 bills and shouting, ‘You didn’t see this,’ ” Duplan says.

Museum and parade officials frequently collaborate on projects that include the museum showcasing parade winners. “There are art car events in about 15 or so cities, but none comes close [to Houston] in the number of parade entries or art cars driven every day,” says Barbara Hinton, longtime Orange Show board member.

Hinton cites several factors, including the city’s status as an arts center and academic support from high schools and the University of Houston’s art programs. Also, she says, “The parade reaches across all demographic sectors—age, ethnicity, income, education, political persuasion.”

Some cars make one-time appearances, but other favorites join the parade year after year: Spectators eagerly anticipate tweaks to the “Sashimi Tabernacle Choir”—aka the Fish Volvo—with more than 250 computer-controlled singing lobster, trout, catfish, sharks and other species.

Mark Bradford has built new cars for 23 consecutive parades, and his most recent creation, “Mr. Green,” won the Mayor’s Trophy (and $2,000) grand prize. It’s a 12-foot walking machine constructed of 99 percent recycled materials and pulling what appears to be an ox cart driven by Bradford.

Inquire at the museum for directions to Bradford’s outdoor workshop a half-mile away. If he’s home, Scrapdaddy is happy to show off his newest endeavors and previous parade entries.

For Bradford and his peers, ingenuity and enterprise are critical with even the classiest creations. Car artists scrounge junkyards, flea markets, pawnshops and dollar stores for materials. “I work with whatever I can get,” says Bradford, who coaxed American Airlines into forking over 6,000 silver utensils for “Spoonazoid” after the 2001 terrorist attacks temporarily prompted a change to plastic. As legend holds, the airline was only hours away from melting down the silverware.

Like most Bradford creations, the design and logistics are remarkable. For “Spoonazoid,” the top opens, Bradford climbs in, then leans back and the lid opens just enough that he can see and steer with controls in each hand. The arms move, jaws open and the beast growls as it proceeds.

Bradford uses recycled materials to make all his drivable hydraulic creatures, including “Carmadillo,” a 50-foot litho-plate aluminum armadillo built over a truck and van with a mouth that opens and a moving head; and “La Rancha,” “an abstract monster,” according to Bradford, with eight legs and 10-inch teeth. “La Rancha” drew enough attention that Bradford shipped it in a container to Germany, where it appeared in a parade he attended in 2009. Other accomplishments include what Bradford bills as the world’s longest bicycle (95 feet).

An accomplished sculptor, welder and television personality (“Junkyard Wars,” “Scrapyard Scavengers”), Bradford says, “I’ve spent thousands of hours on some cars, and I think of myself as the father of my creatures. That’s where the name Scrapdaddy comes from.”

Bradford dreams of establishing an “art-car zoo” for his work: “I’ve done performances with my cars, like a circus thing,” he says. “I hope they can inspire people for years to come.”

——————–

Harry Shattuck is a retired travel editor for the Houston Chronicle; he lives in Houston.

For videos of past Art Car Parades, go to YouTube and type Houston Art Car Parade.