Two minutes after I start blowing a predator call, I see movement to the northeast of the cedar tree in which I am hiding. Out of nowhere a sleek coyote takes a step into a clearing where I’d hoped one might and glares in my direction. Everything I planned to make this moment happen materializes 20 yards away: A predator stands in the burnished orange bluestem in perfect afternoon light and remains motionless long enough for me to focus and squeeze the shutter. I capture two frames of 35 mm slide film, and then the animal disappears. Then I notice my heart is pounding.

In that instant I made my first truly memorable wildlife image. It was exhilarating. Even though the scene is three decades old, I can recall it clearly. It was a defining moment in my eventual career as a photographer.

But here’s the truth: Initially I didn’t know the image was that good. Those were the days before digital photography, when I still had to expose the entire roll of film, ship it to a distant photo lab and wait for the images to return. A couple of weeks passed before I was finally able to look through the cardboard-mounted slips of film and find the coyote. First I thought someone else’s pictures had been mixed in with mine. I quickly realized that the slides were indeed my own. In the Northeast Texas wild, everything I’d learned about how to make an engaging wildlife photo clicked.

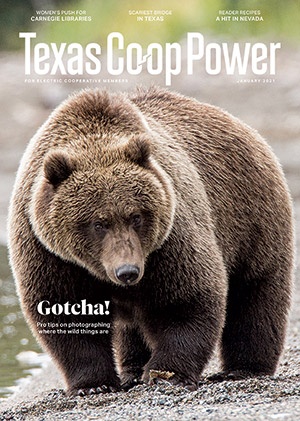

Since that day, my photographs have appeared on more than 500 magazine covers, and I now guide photo tours all over the world. Recently I took a group to photograph bears in Katmai National Park and Preserve in Alaska.

A brown bear atop Brooks Falls in in Katmai National Park and Preserve in Alaska anticipates a meal of a spawning salmon.

Russell A. Graves

A lot has changed since that moment calling up a coyote in Fannin County. A few years after the coyote stepped in front of my lens, digital photography revolutionized how images are made and democratized the medium to the point that even the best equipment made is truly affordable.

Some things have not changed with time and technology. Wildlife is still wild, and the steps required to capture great wildlife images are the same.

Camouflage helps photographers get closer to wildlife.

Russell A. Graves

Here are proven techniques that can help ensure your wildlife images are engaging and dynamic.

Focus On The Eyes

You’ve heard the saying that the eyes are the windows to the soul. That trite phrase holds true for wildlife, too.

When planning a photograph, pay close attention to the eyes. Many cameras now include an eye-tracking feature that can automatically detect an animal’s eyes and ensure that the focus locks on accurately.

A bobcat approaches near Dodd City in North Texas.

Russell A. Graves

The reason the eyes are of utmost importance is simple: When you look at another person or an animal, you first notice the eyes. That’s where you make a connection with the subject. If the animal’s tail is out of focus, that’s OK. Blow the focus on the eyes, and the image suffers.

Get Close

There’s a popular misconception that wildlife photographers use giant lenses and stand hundreds of yards from their subjects to obtain quality photographs. Nope!

To get really impressive photographs of any animal, you must get close. For larger animals like deer, it is best to be within 50 yards. With smaller creatures like quail, try to get within a few feet.

A bobcat approaches near Dodd City in North Texas.

It is possible to use extreme telephoto lenses to get optically closer, but the more air you shoot through, the less sharp your images will be. Since air is filled with particulates, subjects become optically softer as distance increases, so the objects or animals look hazy. It is a good practice in wildlife photography to get as close as you can.

You can achieve the goal of proximity in a number of ways. State and national parks are ideal locations because the animals are accustomed to seeing people and are not as likely to run when they see a photographer. When working in wilder locations, consider including a blind in your setup. Think like a hunter and use the same tools hunters use to get close to wildlife.

Learn About Your Subject

One essential goal of wildlife photography is to control as many variables as possible. You can’t control whether an animal will show up and walk into your line of sight, but you can learn your camera’s features, the craft of photography and the basics of composition.

In addition, learn all you can about the species you wish to photograph. By becoming a student of creative photography and a student of wildlife, you’ll be more likely to see a particular species.

A motion-sensor camera can capture shy animals, such as this badger in Montana.

If you want to photograph mule deer, understand what habitat they prefer and the most likely time to find them. By understanding everything possible about your subject, you will tip the odds in favor of finding your target species.

Think About Composition

Great photographs rely on strong composition. Composition is the arrangement of the elements in a photograph that are visually balanced and pleasing. Typically with wildlife, that means composing them vertically or horizontally and relying on the compositional rule called the rule of thirds. The rule of thirds is a basic guide for where the main interest points in an image should lie inside the frame—a third of the way into the frame vertically and horizontally. This rule discourages centering the subject in the frame.

A bighorn sheep in Montana grazes just a few feet away.

Russell A. Graves

Lighting Is Key

Another essential consideration for a good wildlife photograph is how it is lit. Natural light looks best during the earliest and latest hours of the day. When the sun is low on the horizon, shadows fall away from the subject and the colors cast by sunlight take on a warm glow. The sun’s light is always harshest during the middle of the day. So it is important to be in the field during the beginning and end of the day. Use the middle of the day to review the pictures you shot in the morning or scout for afternoon opportunities. Not only is the light better in early morning and late afternoon, but that’s also when wildlife is most active.

A curious chipmunk in Colorado comes within inches of the camera.

What if the weather is overcast? Overcast days are great because the soft, nondirectional light extends your shooting day. I actually prefer to photograph on overcast days.

Don’t Overthink It

Don’t complicate the process. Photography requires the mastery of a few fundamentals and then doing the same thing over and over so that results become predictable. Today’s digital cameras are capable of performing many functions, but the truth is, a thorough understanding of aperture, shutter speed and sensor sensitivity will make more memorable photos.

Wildlife photography is comparable to golf. Golfers play the game knowing they’ll never be perfect. Top photographers take the same approach. They pursue the perfect shot, and that addictive pursuit keeps them heading afield.

Photographer Russell A. Graves is a member of Fannin County Electric Cooperative.