Bruce Townsley’s favorite place to visit in Japan is Ryoanji Temple Rock Garden in Kyoto. The enigmatic garden has 15 stones, but only 14 are visible to the viewer, no matter where they stand. One side of the garden is arid and stark, but walk around a corner and there’s lush greenery.

It’s the unexpected that gets him.

So it’s little wonder that Townsley’s home in Oplin, south of Abilene, is an illusion all its own. Drive onto his property, and you’ll see a few small buildings and a Quonset hut. But that’s the tip of the iceberg—one that descends 18 stories into the ground.

For the past 25 years, Townsley has lived underground in the two-story launch control center of a decommissioned missile silo. A relic of the Cold War, the 185-foot silo is one of 12 near Dyess Air Force Base that once housed nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles meant to deter the Soviet Union from using their own.

The Atlas F missile sites roughly encircle Abilene like points on a clock face, a silently ticking time bomb that thankfully never had to be ignited—despite veering dangerously close during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

In 1965, the government salvaged much of the metal, removed the 82-foot missiles and sold the silos to private owners and municipalities. Townsley bought his in 1997, and he’s one of several missile silo owners bent on preserving the structures so future generations can learn about and honor this pivotal moment in the Cold War.

Bruce Townsley in his missile silo in Oplin. The crib, the silo’s steel framework, held an Atlas F intercontinental missile in the early 1960s.

Eric W. Pohl

Townsley, formerly a real estate broker in Colorado, initially was interested in the site as a renovation project. He still remembers his first visit to West Texas, crawling into the silo by way of an air vent shaft and shining his flashlight deep inside the cavernous concrete and steel structure.

“It felt like it was—this is going to sound strange—alive,” he says. “It was just like something was sleeping. It wasn’t a frightening feeling; it was just an unusual feeling.”

As with many of the 72 Atlas F silos built across six states, water had seeped into the vast void over the years, and the walls were graffitied with the names of local students who had sneaked onto the property decades ago.

Townsley, a Taylor Electric Cooperative member, purchased the property for $99,000 and set about making the control center into a personal residence. Connected to the silo by a 40-foot tunnel, it once housed a five-man missile crew on its upper floor and equipment and offices on another floor.

After about 18 months of renovations, Townsley began his subterranean existence that has lasted more than a quarter century. He says he enjoys the quiet. The living spaces are white and open, with plenty of lighting and high ceilings.

“You don’t have that sense of claustrophobia,” Townsley says. “Now, some people really react to there being no windows, but cameras and monitors provide a pretty good substitute.”

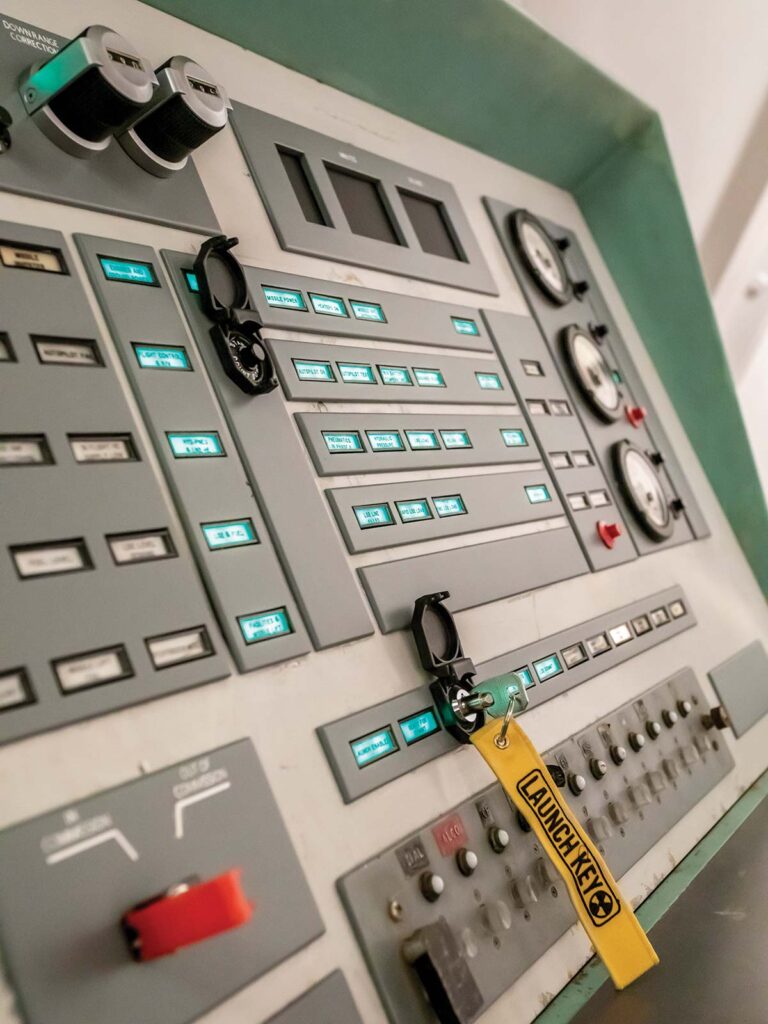

Townsley at the launch control panel of his 1960s missile silo south of Abilene.

Eric W. Pohl

A close-up of Townsley’s Cold War-era missile launch control panel.

Eric W. Pohl

After renovating the control center, Townsley, with the help of others, turned his efforts to the silo itself, draining the water and removing debris (the only bones he found belonged to a coyote and an armadillo). He was also able to get one of the 75-ton, 3-foot-thick silo doors operable so that it once again opens to the sky with the press of a button.

As Townsley renovated the property, he became friends with people who had helped construct the facilities and missileers who served when the sites were active, 1962–65.

“You can’t help but get involved in the history of it,” Townsley says. “It’s just part of it.”

One of the people he met was Roger Jensen, who enlisted in the Air Force in 1961 at age 19 and worked on the Abilene silo sites as an electrical technician with the 578th Strategic Missile Squadron.

Now in his 80s, Jensen still remembers some of the passwords he spoke at the door to gain access to the control center, words like “bicycle” and “wheelbarrow.”

Townsley converted the control center into a living space.

Eric W. Pohl

Mark Hannifin turned his silo in Shep into Dive Valhalla for scuba divers. A staircase and gangplank connect to a floating platform.

Eric W. Pohl

Over the years, graffiti showed up inside the crib of Townsley’s silo.

Eric W. Pohl

“We spent 24 hours in and out of the silo,” Jensen says. “We had to go out into the silo at least once every hour to take specific readings on various pieces of equipment.”

Tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union were high during those years, especially during the 13-day Cuban Missile Crisis, when the Soviets deployed nuclear missiles to Cuba. The Air Force’s Strategic Air Command was at DEFCON 2, one step away from the highest level of readiness for nuclear war.

With a wife and baby in Abilene, Jensen says the possibility of nuclear war became undeniable for the crew. “It was a big dose of reality and what was reality at that time,” he says. The crisis was averted through diplomatic agreements, and Jensen says the crew was “elated when it was over.”

In homage to that history, Townsley had long thought his silo should be turned into a museum, an idea planted by the broker who showed it to him. And in January 2024, he started the Atlas Missile Museum of Texas, a nonprofit organization with a five-member board.

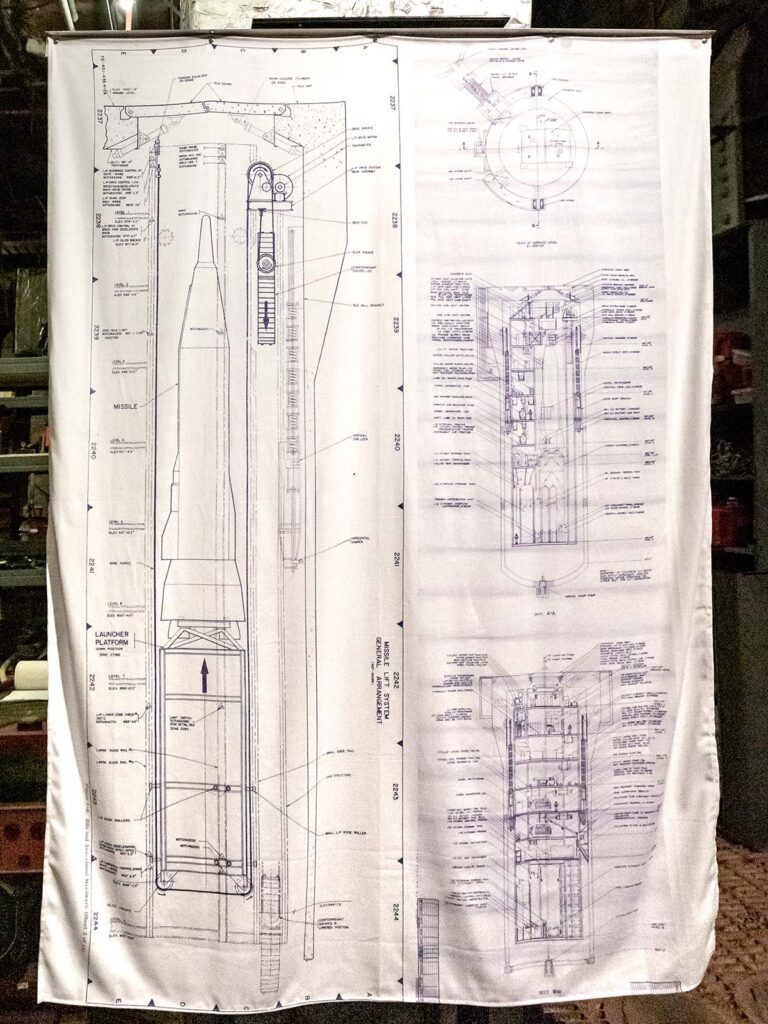

Visitors must make an appointment through his website to tour the silo and control center and learn about the site’s role in the Cold War. They can walk into the silo and see the steel crib once equipped with an elevator capable of raising the Atlas F missile to the surface and launching it in about 10 minutes. Townsley has a model elevator to show how it works and a refurbished control console that simulates a missile launch.

The entry to Larry Sanders’ silo in Lawn.

Eric W. Pohl

Using a model he made, Townsley demonstrates how a silo operated.

Eric W. Pohl

A short drive down the road in Lawn, Larry Sanders is also preserving the history at his missile silo, which he acquired in 1999. Sanders spearheaded a movement in 2001 to get the roadway it sits along renamed to the Atlas ICBM Highway.

He spent years saving the complex from its more recent No. 1 enemy: rust.

“My immediate concern was stabilization,” Sanders says. “You have to keep in mind that water was everywhere. Wood rot, decomposing Sheetrock, metals being compromised totally to rust. So we did nothing for the first five years but demolition.”

Now that the site is stable and clean, Sanders plans to add back infrastructure. Through the Atlas Missile Base Cold War Center, a nonprofit he founded, he holds on-site events and gives presentations to groups about the Cold War, a time that can sometimes get forgotten.

“No one received the recognition and the honor that they deserved in winning the Cold War, unlike World War II,” Sanders says.

A blueprint of Townsley’s silo.

Eric W. Pohl

Townsley installed a shower and sink.

Eric W. Pohl

Townsley’s bedroom and kitchen in what was the launch control center during the Cold War.

Eric W. Pohl

In addition to veterans, Sanders says the heroes of the time include civilian contractors and city administrators. “Texas had a significant role in America’s Cold War victory, and Texans need to celebrate Texas’ role in that victory,” he says.

Like a lot of American schoolchildren in the early Cold War era, Sanders grew up doing “duck and cover” air raid drills in elementary school and watching the political tension unfold on TV.

Mark Hannifin, who owns a missile silo in Shep, also remembers this tense time and tells younger generations that for them, “the Cold War might as well have been in black and white. It’s kind of like us looking at the second World War or our predecessors looking at the first World War and Civil War. No, it was in color. It was a real thing.”

Hannifin and his wife, Linda, bought their silo in 1982 and were “armchair survivalists” at the time, he says. To avoid detection, they used a code word whenever they referred to the facility in public.

An avid scuba diver, Hannifin eventually decided to open the silo for diving and began cleaning out the debris. Their business, Dive Valhalla, hosts scuba dive clubs in the 120 feet of water.

“It’s nice, crystal-clear well water,” Hannifin says. “We have been letting people dive in there for about 30 years now.”

Hannifin at the entrance to his silo, Dive Valhalla.

Eric W. Pohl

One of the blast doors leading to a connecting tunnel and Sanders’ silo.

Eric W. Pohl

Hannifin’s control center is equipped with beds for overnight stays, and he shows a short Cold War documentary and slideshow so visitors are aware of the silo’s original mission.

The Hannifins no longer feel the need to keep it under wraps, and Mark says he’s seen other missile silo owners move from concealing their purchase to being more open about it.

The silos were part of a top-secret mission (although folks in Abilene couldn’t have missed the construction crews that arrived in 1960 to build them). When that secret mission faded, the silos “had fallen out of use,” Hannifin says. “Fallen out of memory.”

But these dutiful owners are ensuring this important history isn’t buried by time.

Jensen, who spent many hours in the silo as a young man during the beginning of his military service, certainly won’t forget.

“If we don’t know our past,” Jensen says, “we can’t live our future the way life is intended to be lived.”