“Government Shocked and Amazed.”

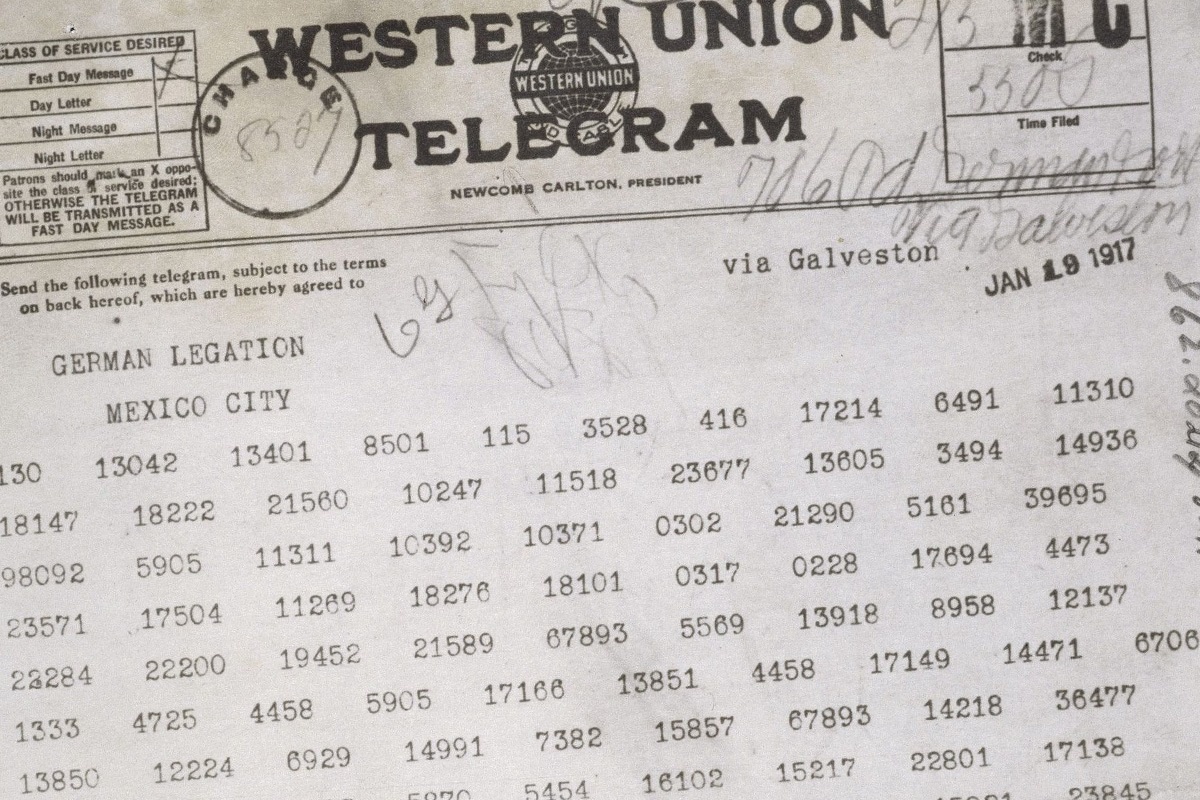

The banner headline blazed across the front page of the Palestine Daily Herald on March 1, 1917. “Revelations of Past Twelve Hours Have Stirred the Capital as Never Before,” read the Sherman Daily Democrat. In newspapers across Texas, The Associated Press story revealed the discovery of a telegram sent from Arthur Zimmermann, Germany’s foreign minister, to the German ambassador to Mexico, Heinrich von Eckhardt.

The incendiary missive outlined a potential Mexican attack on America.

When Zimmermann sent the coded message in January 1917, Germany feared it would not win World War I. The telegram, intercepted and decoded by British intelligence, confided that Germany would intensify its U-boat warfare, attacking the British naval blockade and merchant ships of neutral powers.

If that action drew America into the war, Zimmermann instructed, von Eckhardt should propose an alliance to Mexican authorities. If Mexico attacked the United States, they reasoned, American troops would thus be sent to fight Mexico instead of to Europe. If the effort was successful, Germany promised Mexico it could reclaim Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

The plan may seem far-fetched today, 100 years after the end of World War I, but it’s easy to see why border states, and the entire nation, viewed it with grave concern. Mexico had been embroiled in revolutionary turmoil since 1910, and sporadic unrest had spilled across the border. Even before the telegram, Germans had offered support to Mexican leaders, including Pancho Villa.

Two months later, Mexican combatants attacked the Texas hamlets of Boquillas and Glenn Springs. President Woodrow Wilson, who won re-election in 1916 on the slogan, “He kept us out of war,” sent Army Gen. John J. Pershing and 6,000 American troops into Mexico in pursuit of Villa.

“Events associated with Mexico overshadowed the war across the Atlantic on the front pages of Texas daily newspapers and in the minds of everyday Texans,” wrote historian Patrick L. Cox in the July 2001 issue of Southwestern Historical Quarterly. News of the Zimmermann telegram, Cox noted, “hit the streets of Texas like a political hurricane.”

Historian Michael C. Meyers traced the genesis of the telegram to a document known as the Plan de San Diego. The plan called for a revolution to begin in the southwestern U.S. on February 20, 1915, that would liberate Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and parts of California from U.S. control. “We must not lose sight of Mexico,” the Frankfurter Zeitung editorialized April 15, 1915, “because Mexico will become the focus of a gigantic movement of world power.”

As American authorities worked to authenticate the telegram, Wilson wanted legislation passed that would arm American merchant vessels and authorize their self-defense. Opponents of the move generally changed their minds after the telegram’s publication March 1. Isolationists also supported the United States’ declaration of war April 6, 1917.

The Zimmermann telegram, along with Germany’s waging of unrestricted submarine warfare, is often cited as a major impetus for America’s entry into the war. But the most recent major work on the storied communiqué, the 2012 book The Zimmermann Telegram: Intelligence, Diplomacy, and America’s Entry into World War I by military and intelligence historian Thomas Boghardt, contends that the Zimmermann telegram was much less important as a motivation to declare war than the German declaration of open season on American merchant ships.

Still, Austrian native and North American immigrant Friedrich Katz, who became one of Mexico’s most important historians, said in his 1981 volume, The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution, the Zimmermann telegram “has become one of the great spy stories of all time,” albeit one that “boomeranged.”

Writer Gene Fowler specializes in Texas history.