I’m sloshing through a marshy field in Matagorda County, along the Texas coast, a pair of binoculars dangling around my neck and cold raindrops pelting my bright blue jacket.

A hundred yards away, ornithologist Rich Kostecke points toward a cluster of what looks to me like a group of white footballs on stilts. I slap a mosquito off my arm and take a closer look: egrets.

We’ve just ticked off another species in the annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count, which takes place across the country between December 14 and January 5. The event got its start on Christmas Day in 1900. Instead of holding a hunting competition, as was popular at the time, an ornithologist and Audubon Society officer named Frank Chapman came up with a less destructive alternative: Count—but don’t shoot—the birds.

The idea caught on. Today, tens of thousands of birders participate in counts in all 50 states and in 20 countries. During the 2021–22 count, they logged almost 43 million birds at more than 2,000 sites.

I’m new to birding, but I love tromping around outdoors, and I could spend all day watching wildlife. Besides, it feels good to contribute to science, and this annual count provides data that sheds light on long-term avian trends.

But joining the Matagorda County-Mad Island Marsh Preserve count is especially exciting. The plot where I’m birding—a circular area with a 15-mile diameter—almost always records more species than any other area in the country.

A painted bunting’s breeding grounds include much of Texas.

Erich Schlegel

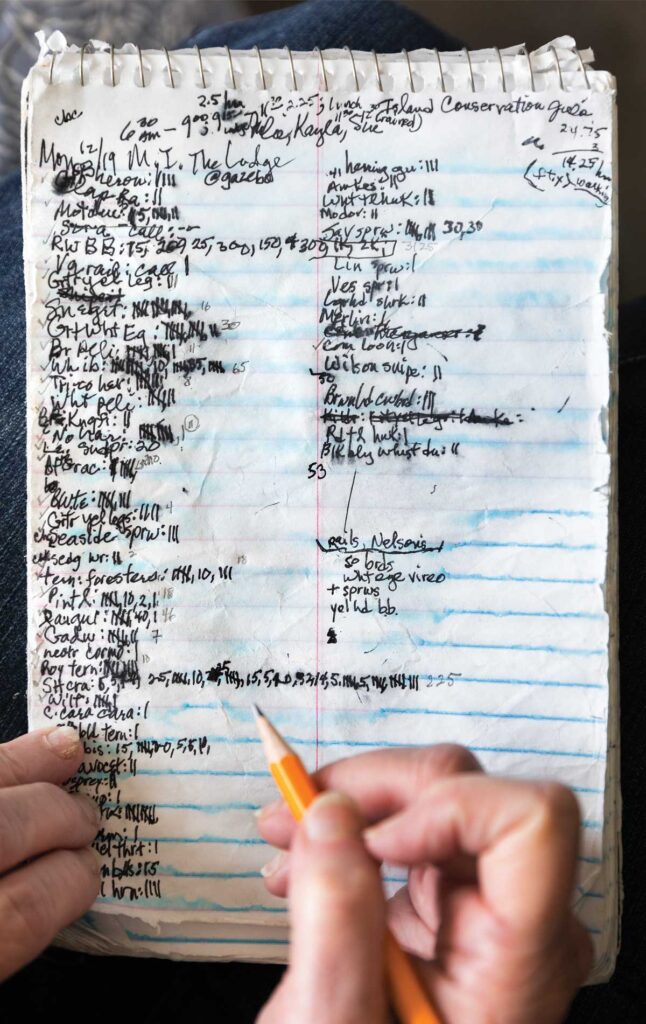

Unforgiving December weather leaves Sue McBeth Welfel’s notebook a bit soggy.

Erich Schlegel

The Matagorda County count began 30 years ago when Brent Ortego, then a biologist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and Jim Bergan, formerly of the Nature Conservancy, realized they could position a count circle that would incorporate a bit of the Gulf of Mexico, a stretch of coastline and some land along the Colorado River. Much of the 176-square-mile plot is on private land, but it also includes the Nature Conservancy’s Clive Runnells Family Mad Island Marsh Preserve and the neighboring Mad Island Marsh Wildlife Management Area.

It’s fertile territory for birding.

“A lot of habitats come together here—coastal prairie, marshes, bay and forest,” says Kostecke, who heads the small team to which I’ve been assigned for the count.

Under the bird count guidelines, teams tally all the species they see during a single calendar day. You don’t need any special training or certification to participate, but only birds spotted by knowledgeable birders figure into the official total. Still, newbies like me typically can participate if there’s room.

“It’s a repeated count at the same time, year after year, so we’re getting a snapshot across the nation over that time period,” Kostecke says.

Sandhill cranes were quite plentiful during the count.

Erich Schlegel

Rich Kostecke adds birds he spotted to his list using the mobile app eBird.

Erich Schlegel

In a typical year, birders here log about 230 species during the count. But today’s stormy weather doesn’t bode well.

About 100 birders are participating in the count this year. Last night we lined up for bowls of chili and hot cornbread and talked strategy.

One group would watch for yellow-headed blackbirds. Another would head out at night, hoping to flush out tiny yellow rails and black rails in the darkness. The circle was divided into 16 sectors, with groups assigned to each one. We knew the weather would be a challenge because, like humans, birds hunker down in the rain.

“We may have to work harder to get them out,” says Ortego, the official compiler for the event.

The count officially begins at midnight. I’m tucked inside my camper van then, but a hardy group of birders heads into the night to look for owls and other nocturnal birds.

I meet my team—Kostecke, along with ecologist Charlotte Reemts, her husband and their two daughters—early the next morning, which dawns gloomy and damp.

We pile into two cars then head down a gravel road, stopping periodically to scan the surroundings.

Within 20 minutes, Kostecke has already logged 10 species. He doubles that when we reach a lake, and his list grows further when we hike into the brush and eventually reach the marsh. I love birding but definitely do not know my birds, so I leave the identification to the experts.

We spend all morning admiring turkey vultures perched in trees and great blue herons wading in the water. At noon, we head back to headquarters. Raindrops plunk on the roof; it’s foggy outside. Birders peel off soggy rain jackets as they come in for a break.

“What did you get?” someone asks a dripping man who walks in.

“Wet,” he responds with a chuckle.

Ella Reemts, 14, uses a scope to count a group of birds along the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway with her mother, Charlotte Reemts; Kostecke; and author Pam LeBlanc.

Erich Schlegel

Kathy Sweezey of the Nature Conservancy looks to escape the rain at the Mad Island lodge.

Erich Schlegel

The birders munch leftover chili and discuss what they’ve spotted. So far, no one has recorded anything that’s never been seen here before. But they have logged lots of birds, from Pepto Bismol-colored roseate spoonbills to pelicans, crested caracaras, white ibises and plenty of noisy sandhill cranes.

“There’s still quite a few rocks to turn over,” preserve manager Steven Goertz says as the birders head out for the rest of the day.

In the end, the Matagorda County-Mad Island Marsh Preserve circle reports 218 species, enough to retain the crown for the most species in the country. A count in San Diego comes in a close second with 213. It marks the 24th time this corner of Texas has come in first or tied for first—and the 15th straight year it has topped the list outright.

But the rain took a toll. A dozen species usually recorded here weren’t seen. Still, they got some good ones—the scaly-breasted munia, with its checkerboard chest; a squat-looking bird with an impressively long bill called a green kingfisher; the rose-breasted grosbeak, the male of which looks like it’s wearing a red bandana around its neck; the Western kingbird, with its lemon-colored belly; and the tall, spindly wood stork.

They also found one that I’ve long wanted to see—the tallest bird in North America, the whooping crane, which stands nearly 5 feet tall and has a wingspan of 7½ feet. Whooping crane numbers dropped to about 20 individuals in the 1940s but, thanks to conservation efforts, a population of about 600 now exists in the wild. They winter near here.

“It’s an adrenaline rush,” Ortego says of the count he helped start. “It’s pride that you had the skills to locate an unusual bird when people are counting on you.”

The count has scientific value as well. Biologists have seen a reduction in the raw number of birds in the past 50 years, and the counts provide evidence.

“For us, these data sets are important because the populations of birds that they monitor are not the subject of any formal monitoring program,” says Lisa Gonzalez, executive director and vice president of Audubon Texas.

Since 1970, the population of birds in North America has dropped by 3 billion birds, or nearly 30%, she says.

Much of the loss is due to human activity. “Collisions and impacts are one of the major causes of bird loss, along with overall declines in habitat and a change in environmental conditions driven by climate change,” Gonzalez says.

The public can help.

“Share the shore,” Gonzalez says. “If you live or recreate along the coast, understand that it doesn’t take a lot to disturb birds, especially nesting birds. When you’re boating or fishing, steer clear of islands where birds nest—and keep dogs on a leash.”

Watch for birds that nest on the ground when you drive on beaches, and turn off unnecessary outdoor lights during spring and fall migrations. And, if you’re willing to spend a day outside looking for a flash of feathers, consider joining a bird count in your area.

“It’s a fun thing to say we have the No. 1 count, but the count would be fun even if we weren’t No. 1,” Reemts says. “It’s just all about the experience of being out here and seeing stuff.”

Black-bellied whistling ducks seem to be standing guard.

Erich Schlegel

Steven Goertz, manager of the Mad Island Marsh Preserve, reads out names of birds to the counters during lunch.

Erich Schlegel

A soaring sandhill crane.

Erich Schlegel

Photographer Erich Schlegel was up to his knees in muck as he slogged his way around the Mad Island Marsh Preserve in December.

Pam LeBlanc