Frozen water—so simple, yet so taken for granted. It conquers a sizzling day like water extinguishes fire.

In steamy Texas, wherever there’s electricity, there’s ice—in just about every home, restaurant, convenience store and grocery market. The sweltering truth is that for most of Texas’ history, there was precious little ice to tame the dog days of summer.

In fact, until the mid-1800s the only ice in Texas—except during winter—came from cold-climate northern states. Natural ice was cut from frozen lakes and rivers up north, then transported via sailing ships to ports like Galveston.

The ice trade helped preserve food and drink for a growing coastal population. Inland families were left to rely on the time-tested preservation methods of drying, smoking, salt-curing and pickling the foods they raised.

During the Civil War, Union blockades of Confederate ports cut off the northern ice supplies. So in 1862, desperate Texans smuggled in—via Mexico—a French-designed Carré ice machine that used ammonia to absorb heat and freeze water.

In 1865, Daniel Holden redesigned and installed a more commercially promising Carré machine in San Antonio.

The artificial ice cost 5 cents a pound, half the high rate of New England ice at the dock. But with beefsteaks selling for 2 cents a pound, artificial ice remained, according to a local paper, “one of the greatest luxuries of civilization.”

Shortly after the Civil War, ice in the Alamo City was so important that the city sported three of the nation’s eight ice plants.

The original exterior neon sign now hangs in the Ice House Museum’s indoor main gallery.

Equipment that made carbonation and carbonated water for soda pop production from the Casey Roby exhibit in the Ice House Museum on bottling works that once accompanied ice manufacturing.

Ice as Utility

Ice was so useful in Texas that some early electric distribution companies operated ice plants as a public service. Powered by direct-current electric motors or steam- and gas-powered engines, these icehouses operated in many towns.

One of the few remaining southeast Texas icehouses sits beside the railroad tracks in Silsbee.

The icehouse was incorporated in 1909 to make ice and to bottle soda pop. The original facility burned, but in 1915 it reorganized as Silsbee Ice, Light and Power Co.

In fact, Texas’ passion for human-made ice led to many firsts in the artificial ice industry.

The first refrigerated beef shipments traveled by boat from Palacios and Indianola to New Orleans in 1868. The first refrigerated slaughterhouse opened in 1871 in Fulton. The first commercial ammonia-compression plant was built in 1873 in Jefferson. That same year brought the first refrigerated meat shipment cross-country by rail from Denison to New York.

Early meat-shipping successes proved to be the tip of the iceberg commercially. During the late 1800s, as railroads cobwebbed across the state, they began transporting perishables in railcars refrigerated with ice blocks enclosed in insulated corner bunkers. The melting ice had to be replenished, so ice plants and storage houses popped up all along the rail lines.

Assured of cold shipment to far-off buyers, Texas’ beef, fruit and vegetable industries expanded like never before.

Trucks are ready to make deliveries for the Lufkin Ice Co. in 1940.

Locals celebrate the ice house opening day in 1930.

Courtesy Ice House Museum

Gulf States Utilities took it over in 1926 and constructed the current building. The Spanish Revival-style, red-tile roofed structure was described by many at the time as “beyond a doubt the most modern structure in Silsbee.”

Now home to the Ice House Museum and Cultural Center, the distinctive facility tells the story of ice and illuminates other little-known topics of regional history.

It looks much as it did almost a century ago. Near the entrance sits the original well, well house and waterlines that carried water to the icehouse. Other original lines lead toward the adjacent railroad sidetrack where locomotives took on water for their steam engines, according to Susan Kilcrease, museum director.

The building boasts the original loading docks where a dozen or so employees catered to local customers and loaded ice blocks into insulated railcars for shipment.

“It was a very busy place—a community gathering place, really,” said Kilcrease, a Silsbee native with deep local roots. “When I was a kid, I remember coming to the dock and ringing the service bell. I was fascinated when a huge block of ice would slide out of the chute, and we’d load it onto our truck.”

In addition to selling ice and chilled bottled beverages, the icehouse also had hooks inside its cold storage vault where locals could temporarily hang a side of beef or a deer. Seasonally the icehouse kept watermelons cold for sale, a rare treat before home refrigeration.

Inside today’s museum, information panels detail the artificial ice production process.

Well water was filtered and pumped into galvanized cans that could each hold 312 pounds of ice and required cranes and hoists to move. It took 36 hours to freeze the facility’s 336 cans. The process produced an average of 30 tons of ice a day, sold locally and shipped out on railcars to towns across southeast Texas.

The Ice House Museum in Silsbee appears much as it did when built in 1927 by Gulf States Utility.

One room in the colorful museum shows carbonation and capping equipment like that used for soda pop production in Silsbee and other nearby towns. The equipment and displayed soda bottles come from local collector Casey Roby’s bottle museum.

On display in the main ice factory space is a 1902 Studebaker wagon. A 1920s-era kitchen features a period icebox where ice blocks kept perishable foods from spoiling in the days before fridges. To meet growing home demand for cold goods, icehouses began delivering ice blocks door-to-door to subscribers.

Made of wood, lined with tin or zinc, and insulated with materials such as cork or sawdust, the icebox contained one compartment for ice and another for food. A drip pan under the icebox collected water from the ice melting and had to be dumped periodically.

Messy as it was, this appliance transformed ice from a luxury to a necessity. Its legacy lives on every time an East Texan says “icebox” instead of refrigerator. In front windows, customers placed a square cardboard sign with numbers—10, 20, 30 or 40 pounds—informing the ice delivery crew how much to bring inside.

The iceman’s job could prove a slippery challenge, explained Darrell Shine, Kilcrease’s father, in a 2000 interview. As a boy, Shine delivered ice seven days a week each summer with his grandfather, Jim Shine, who drove Silsbee Ice Co.’s delivery wagon.

Shine remembered that at 10 or 12 years old it was hard to carry a 50-pound block and work around the ice hook to get it into the icebox. “Sometimes you’d accidentally knock stuff out. Many a time I’ve cleaned up milk spilled on the kitchen floor,” he said.

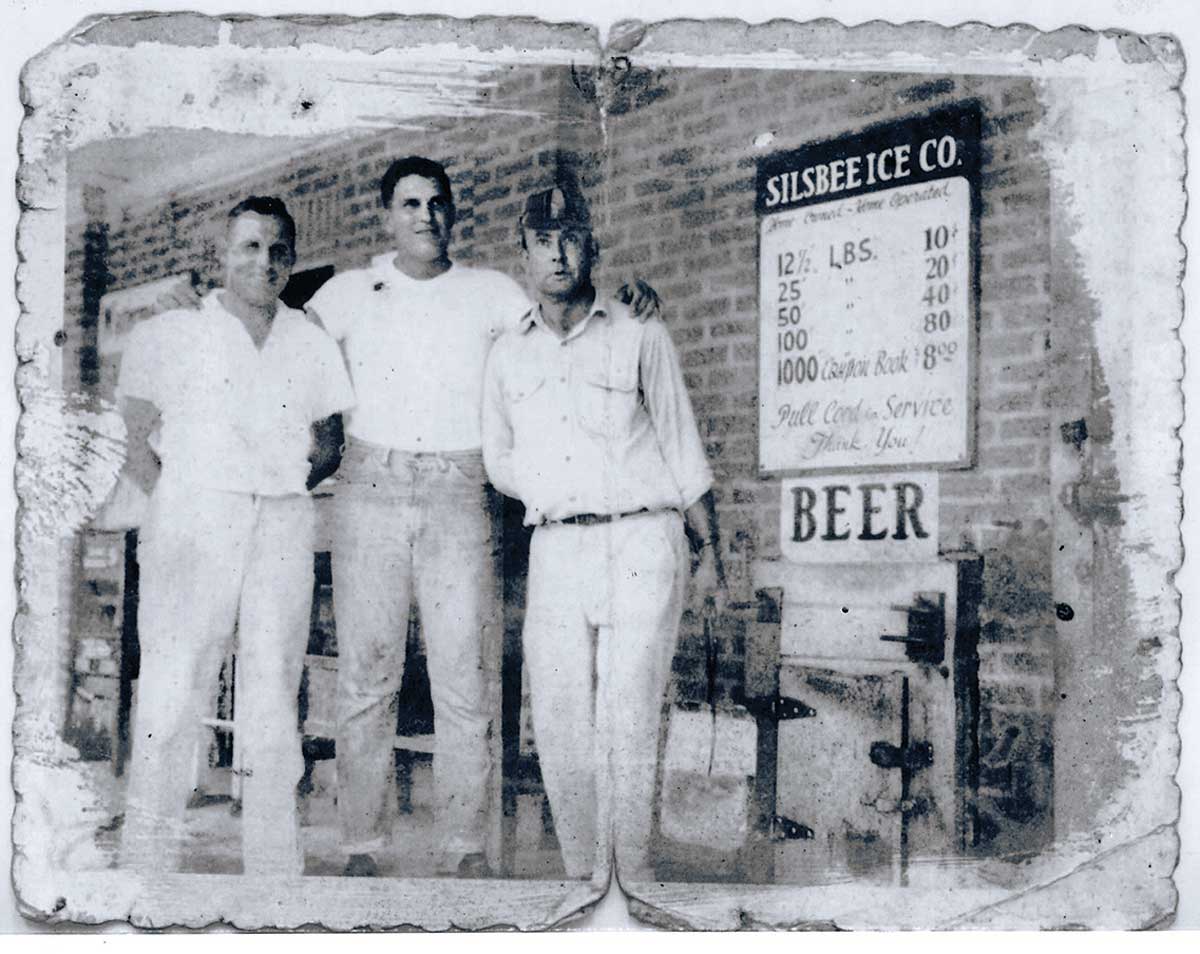

From the Ice House Museum in Silsbee: Icehouse workers at the loading dock.

Ice. Cold. Beer.

The ice industry and the beer business have long advanced side by side.

Lager-style beer has been popular in hot-weather Texas since German brewers immigrated in the 1840s. Lager beer required brewing and storing at cold temperatures, so it was originally brewed in Texas only during cold weather. With the advent of artificial ice, breweries could make lager year-round.

Demand for ice also grew for home use so much that ice manufacturers began opening neighborhood pick-up stations, also called icehouses. In Dallas the Southland Ice Co.—now 7-Eleven—embraced the practice and added sales of groceries and other items. These icehouses set the stage for today’s convenience store industry.

Other icehouses focused on selling beer at open-air establishments, often featuring patios and picnic tables. These popular beer joints served as outdoor neighborhood watering holes in the days before air conditioning. The term “icehouse” in fact still brings to mind these uniquely Texan beer parlors found in many cities.

Rural electrification and the widespread use of electric refrigerators eventually reduced the need for block ice. In response to the changing marketplace, ice manufacturers zeroed in on cubed and crushed ice used for water coolers, parties, picnics and sports events.

Indeed, record-setting Texas heat still seems to fire up our collective gratitude for one of life’s most common luxuries—clear, cold ice!