In the quiet little Central Texas community of Hearne, a huge part of forgotten Texas history is on public display. More than a decade ago, Texas A&M University professor Michael Waters, along with more than 300 graduate and undergraduate anthropology students, unearthed more than 1,400 artifacts from one of the 70 prisoner-of-war camps established in Texas during World War II.

And now, the Camp Hearne exhibit and visitors center, opened to the public in 2010, houses many of those invaluable pieces of history as it tells the story of what life was like in the German POW camp.

In 1942, hoping to secure economic prosperity for their agricultural community of 3,500, the civic leaders of Hearne lobbied for the construction of the POW camp. Waters details in his book Lone Star Stalag: German Prisoners of War At Camp Hearne (Texas A&M University Press, 2004) why Hearne fit the criteria for an ideal camp location: It was in a rural setting far from crucial war industries; it was not within the coastal blackout zone (which extended 170 miles inland from the coast); and it was more than 150 miles from the Mexican border.

Fascinatingly, Texas had about twice as many POW camps as any other state because of ample space and climate: The 1929 Geneva Conventions required that prisoners of war be moved to a climate similar to that of where they were captured. It was thought that Texas’ weather conditions resembled those of North Africa, where some German POWs surrendered.

The U.S. government concurred, and plans were under way immediately for what was not only one of the first, but one of the largest internment camps in the U.S.

The government bought 720 acres from five landowners for $27,500, and Camp Hearne was officially activated on December 15, 1942, with the capacity to house 4,800 prisoners.

The camp consisted of 250 buildings, divided into three main areas—the POW compounds, the hospital and the American sector. Three prisoner compounds, each composed of 50 buildings on 8 acres, included barracks, a mess hall, a company office, a lavatory and an office. Also in each compound were an administration building, an infirmary and a post office. Two recreation buildings served the entire compound.

Two 10-foot barbed wire fences surrounded the compounds, hospital and recreation areas, with seven guard towers bordering the property.

“There were 1,800 miles of wire around the camp,” says Melissa Freeman, program director for the Camp Hearne exhibit. “Enough to stretch to Chicago and back.”

During World War II, soldiers in German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps were the first of many in the Axis forces to surrender to the Allied powers. After a nerve-wracking voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, these German soldiers were housed in more than 650 POW camps across the United States. By June 1945, there were approximately 371,000 Germans, 50,000 Italians and 4,000 Japanese POWS in the U.S.

POWs were allowed to receive food from home, and packages of bread, sausages and cake were always a welcome reminder that they had not been forgotten.

At Camp Hearne, prisoners initially were allowed to write two letters and one postcard per week, with letters not exceeding 24 lines. In 1943, those privileges were reduced, with enlisted men and noncommissioned officers (NCOs) now allowed to send only one letter per week.

At times, the postal service helped carry out long-distance marriage ceremonies. The German bride would mail legal papers, signed before two witnesses to Camp Hearne. When received, the intended POW husband would sign the papers—also before two witnesses—and the American chaplain, along with the highest-ranking prisoner, would officiate the nonreligious procedure. The couple were pronounced married “in the name of Hitler and the Third Reich.”

Within the three main compounds, prisoners kept a fairly strict schedule. In accordance with Geneva Conventions guidelines, NCOs did not have to work. The remainder of the POWs spent their days at work in nearby fields, earning the same wages as civilians.

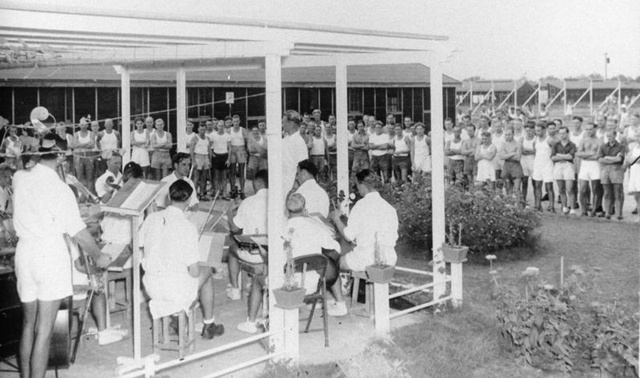

Leisure time was spent playing soccer, woodworking or making major improvements to the camp, including building elaborate fountains and constructing a theater in which the POWs produced plays, such as “The Merry Widow,” for the community.

College courses such as business, technical training, history, chemistry and bookkeeping were sponsored by Baylor University. Not only did the courses meet the POWs’ desire to learn, they did much to prevent boredom.

Reading was a popular pastime, and by 1945, the complex’s library offered approximately 7,000 German and 500 English books.

Many of the prisoners also regularly attended church services at a chapel on the premises, and POWs and NCOs were given $3 per month in coupons that could be used to purchase items in the canteen, or general store. Many civilians felt the Germans were treated too well and dubbed Camp Hearne the “Fritz Ritz.” Other Texas communities called their POW camps by the same name.

Alcohol was prohibited on the property, but some of the POWs found ways to circumvent the rule. They made it secretly using, fruits, sugar, yeast and 1-gallon jars obtained from the kitchen. The jars were buried in a hole under the barracks or hidden in the rafters, with the concoction fermenting. A second option was to filter shaving lotion, aftershave and shave tonic (all containing alcohol) through a loaf of bread. What emerged was pure alcohol.

The greatest danger to the prisoners was not from Americans, but rather from the turmoil present in the POW ranks—the Nazi versus anti-Nazi beliefs. After it was infiltrated by the former, the postal service at Camp Hearne was closed and all mail was redirected to a mail distribution center at Fort Meade, Maryland.

When Germany surrendered to the Allies on V-E Day, May 8, 1945, Camp Hearne held 3,855 POWs. They were slowly removed, sent to other camps in Texas and the U.S. to help with agricultural work before finally getting to go home. By late December, the last POWs remaining at Camp Hearne were shipped out.

The camp was dismantled, with many of its buildings sold to the community to be used as offices, warehouses and even a church parsonage.

Today, Camp Hearne is being brought back to life for posterity’s sake. Waters, a professor in the departments of anthropology and geography at Texas A&M, says the excavation experience was especially important for undergraduate students, who learned about archaeology and recorded artifacts dug up in the field. Some of the work uncovered portions of “The Kneeling Woman,” “The Devil” and “The Castle” fountains built by the prisoners, along with small objects, such as rings, knives, engraved canteens and badges.

Waters says few of Texas’ smaller branch POW camps remain, and the larger camps have limited remains and limited access. “None of the other POW camps have ever been studied like the Hearne camp,” he says. “It is the only camp where they are actively trying to do historic preservation and interpretation and have obtained funds to build a museum and walking tour through the camp.”

Cathy Lazarus, president of ROLL CALL: Friends of Camp Hearne, a group dedicated to preserving and teaching World II history, says the Camp Hearne experience will continue to develop with the addition of a replica guard tower, trails to the remains of two POW-built fountains and a theater, and replicas of fountains and band stands built by the prisoners.

Inside the museum housed in a metal barracks replica, you quickly realize you’ve stepped back in time. More than 60 years ago, German prisoners wore the uniforms, carried the field equipment, ate from the mess kits and drank from the canteens that are now on display.

——————–

Connie Strong is a freelance writer based out of Chappell Hill.