In the early 1930s, the game of marbles was the king of sports in country schools. Times were hard, and money was scarce. Sophisticated toys were out of reach for most families, but a web pouch with five marbles cost a nickel at Perry Brothers 5 & 10 Cent Store in San Augustine. For some youngsters, this was all they got for Christmas.

Most marbles were perfectly round, about a half-inch in diameter, and were made out of glass and penetrated deep inside with a variety of brilliant colors. A few were made of steel, stone, baked clay or other materials with 1/3- to 2-inch diameters. But veteran shooters always went for glass.

Rosevine, in Sabine County, near the Louisiana border in East Texas, was a typical country school where children either walked or rode a flatbed truck converted into a school bus. Many arrived before the first bell rang and had time to start a new day of games. Girls, the majority wearing feed-sack dresses and bows in their hair, opted for hopscotch or jacks. Some of the boys started a game of deer and dog where “dogs” chased “deer” between two bases—a large white oak and a giant sweet gum. But for the rest of the boys, marbles were king.

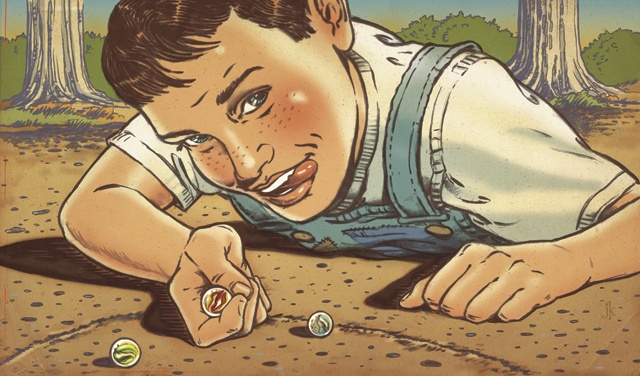

The boys typically wore blue or striped overalls, went barefoot and carried pocketknives. The overalls were made of durable material that could take multiple patches. Shoes were too costly, and the pocketknives were used for cutting watermelons, trimming fingernails, digging marble holes and carving girlfriends’ initials in the desktop when the teacher wasn’t looking.

Grover Eddins was the No. 1 marble ace at Rosevine. His taw (favorite shooter) was clear with two yellow streaks shot through and connected by a shaft of bright red. He shot with his right hand, palm up, knuckles touching the ground, his index finger curled in, and his taw balanced between the tip of the index finger and his thumbnail. When he fired, it usually hit the opponent’s marble dead center, sticking his taw on the spot and sending his opponent’s taw far out of the ring.

The campus was naked, sandy soil; the pounding of bare feet had long since killed any grass, making it easy to dig marble holes. But the lightest rain could wash them out.

John Robert was second ace and fighting to move up. He and Grover came early each morning and warmed up with two or three games of rolley-holey. The most common game—and one endorsed by the school principal—was played with four holes, three in a straight line and the fourth at a right angle to the third. The holes were named “first,” “second,” “third” and “rover.”

The object was for the player who had won the lag (shooting to see who could get the closest to a designated line) to take a span (placing a thumb at the shooting spot, extending and spreading the fingers to make an arc, and shooting from the tip of the arc) at first, knuckle down and shoot at second. If made, he continued by shooting at third and then rover. If he missed, he lost his turn. When the player made rover, he turned around and shot his way back to third, second, first and diagonally across to rover. At that point, the player was finished with the four holes and became a rover with the power to knock out his opponent and win the game.

When the two aces matched their skills, word spread, and an audience of boys and girls quickly gathered. Rolley-holey was strictly prelim, and it was time to move up to more exotic games such as bun-hole, cherry pit, hundreds, chase or ringer.

The two titans chose ringer. It had an air of sophistication and was played by the better shooters. A two- or three-foot ring was drawn with a bull’s eye in the center. Each player put a number of marbles on the bull’s eye. Shooting order was determined by lagging. With the initial shot from outside, each player tried to knock as many opponents’ marbles as possible out of the ring while keeping his taw inside. As soon as his taw stopped outside, he lost his turn.

School rules prohibited any form of gambling—no betting was allowed. All marble games were played for “funzies.” No one had money, but there was betting, and the chips were marbles. For onlookers, bets sometimes included white oak acorns or chinquapins. On rare occasions, betting reached a zenith when the individual pictures of two class beauties were at stake. Games with the purpose of winning the opponent’s marbles were called “keeps.”

Back then in rural East Texas, one could hear the sharp clack of glass against glass. Anyone looking for the best marble shooters in the world could have started right there with Grover Eddins and John Robert, when marbles were king.

——————–

Harry Noble lives in Iola and is a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power.