The room was grim and silent, save for the rustling of papers. Lady, Rudy and Chanel—two yellow Labs and a golden retriever mix—slipped in as police officers studied security camera footage, surveying the aftermath of the shooting that left 23 people dead at an El Paso Walmart in 2019. The dogs knew what to do.

“Lady started making herself known to those who were going through security footage,” says Frankie Trifilio, Lady’s handler and one of three emergency medical services managers who flew to El Paso with the dogs from Methodist Healthcare in San Antonio to support first responders. “When Lady rolled on her back, a tall, muscular guy who looked like a member of a SWAT team asked me, ‘What is she doing?’

Trainees at Service Dogs Inc. near Dripping Springs.

Laura Jenkins

“I said, ‘She’s making herself available. She likes belly rubs.’ ”

The officer went back to what he was doing. But within a matter of minutes, he succumbed.

“He knelt down and started rubbing her belly, saying, ‘Oh come here. Who’s a good girl? Who’s a good girl?’ ” says Trifilio. “That was the catalyst for others to interact with the dogs, and suddenly everything came alive. Everyone started talking. There was laughter. When we left, people were communicating and collaborating. I can only speculate that it helped with the investigation. But I know firsthand that it helped those officers personally and emotionally.”

Providing trained dogs for people in need is nothing new to Sheri Soltes, founder and president of Service Dogs Inc., the organization that trained and placed Lady, Rudy and Chanel. An attorney by trade, Soltes was headlong into a successful career more than 30 years ago when she realized that the stress of the job was taking a toll on her health. She was living in Houston when she started thinking about a career change. At the time she had no idea what was next.

Sheri Soltes, president and founder of Service Dogs, with Poppy, a trainee.

Laura Jenkins

“One day I was at the eye doctor and picked up a magazine that had an article about dogs helping people with disabilities,” says Soltes. “At the end it said that some of the groups used dogs from animal shelters, and that appealed to me because I’ve always been drawn to animals, especially those in need.”

Soltes saved the article and contacted organizations mentioned to find information that would help her build a nonprofit. She conducted a survey in Houston to see how many hearing-impaired people might be interested in a hearing dog; 75% answered affirmatively. Then she found a local dog trainer who agreed to visit shelters with her and help her find dogs best suited for service.

What began in 1988 as a home-based, one-dog-at-a-time endeavor has grown into a 6-acre campus near Dripping Springs, complete with a training facility, kennel and devoted team of trainers and caregivers. Even though SDI, a member of Pedernales Electric Cooperative, has placed more than 750 assistance dogs over the years, the operation is no assembly line. Soltes says they’ve developed an “artisan” approach to training because they select, train and match dogs to meet each client’s specific needs.

Becky Kier, a former trainer at SDI, leaves the Humane Society of the New Braunfels Area with Lily, who is now in hearing dog training.

Laura Jenkins

It might seem like any dog could be trained to mitigate any disability, but Becky Kier, former director of training at SDI, explains that when it comes to assistance dogs, one size definitely does not fit all.

“What they all have in common,” says Kier, “is that they’re all super sociable, obedient and have really good temperaments as far as loving and accepting all humans and animals. They’re not rattled by anything. But beyond that it comes down to the disposition of each individual dog. A hearing dog, for example, must take cues from the environment. We teach them what to do at first, but at some point, they have to take ownership of that.”

Kier says guide dogs for the visually impaired are hardest to find because they must be obedient and proactive without a lot of redirection. Even though SDI does not train animals to serve people with visual impairments, it does get a lot of “career-change” dogs from Guide Dogs for the Blind, the largest guide dog school in North America. Career-change dogs can have an excellent temperament, but they can also have qualities and traits that disqualify them from guide dog service.

Austin Meredith, a senior computer science student at the University of Houston-Clear Lake, and his service dog, Peaches, live on campus.

Laura Jenkins

“One of our recent graduates, Sensi, was released from GDB for not liking to work in the rain,” says Kier. “She didn’t want to guide through puddles. But she’s an ideal hearing dog.” Kier notes other examples of career-change dogs, such as Artist, who needed more supervision in the home than a blind person could provide, and Tootsie, who didn’t like the guide harness. “Dogs have idiosyncrasies just like people do,” she says.

Before the partnership with GDB provided career-change animals, all of SDI’s dogs came from rescue organizations. Many still do. For more than three decades, Soltes and her team have been searching animal shelters, offering a life of love and service to abandoned and unwanted dogs. Kier found Sherlock, a terrier mix, on a routine visit to the Humane Society of Central Texas. After his training, he was partnered with Megan Harris of Austin, who’s had a hearing impairment since she was 15 months old.

Sherlock has been assisting Megan Harris of Austin for eight years.

Laura Jenkins

“Before he entered my life, I didn’t feel comfortable being left at home by myself,” says Harris, who has been partnered with Sherlock for more than eight years. “Anybody could enter the house at any moment, and I wouldn’t hear them. I worried about hearing smoke alarms, the doorbell and timers. Once Sherlock became my hearing dog, I felt more relaxed and at ease at home and in public.”

In the beginning Soltes was focused solely on the need for hearing dogs. But before long others began asking if she could train dogs to meet other specific needs, and SDI expanded its programs.

“A couple of years into it, a young man who had become paralyzed from the shoulders down asked if we could train a service dog for him,” says Soltes. “Another woman with paraplegia did too. We weren’t sure, so we did two as a test run, and it was successful.”

Soltes thrives on the challenge of innovating new programs to meet the needs of those who seek help.

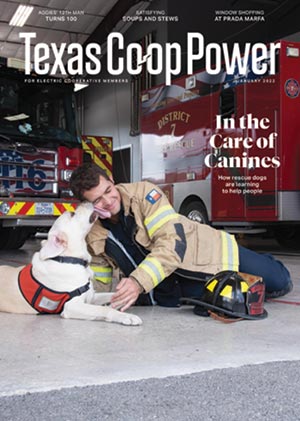

First responders with Bexar County District 7 Fire & Rescue with Rudy.

Laura Jenkins

“A few years ago, we were at a Texas Medical Association conference in Houston and a battalion chief said to me, ‘Our suicide rate is approaching that of veterans. Can you help us?,’ ” Soltes says. “I took that information, did some research, and we created a program that provides dogs to support first responders.”

Lady, Rudy and Chanel are a result of that initiative.

Patty Maginnis, a district court judge in Montgomery County, with Sumi, who provides victim support in the courtroom.

Laura Jenkins

Soltes says it takes approximately $50,000 to adopt, train and provide lifelong follow-ups for one dog. Despite that cost, SDI provides each one at no cost beyond nominal application fees and personal travel expenses. They rely on donors, sponsors, grants and fundraisers to operate. But Glenda Ann Kea says you can’t put a price tag on the profound difference SDI is making in the lives of Texans with disabilities. When her systemic lupus became debilitating, she got so depressed she stayed in bed for nearly two years.

“At that time the doctors were prescribing me tons of narcotics because I was in so much pain,” says Kea, who lives in Allen, north of Dallas. “I couldn’t get up on my own and I didn’t want to. I didn’t see the point. If I dropped something, my day was over because there was nobody there to help me pick it up. Seriously, I wanted to die.

Methodist Healthcare EMS relations managers and their dogs.

Laura Jenkins

“But when I got DaVinci, I had to brush him and feed him, so I’m moving and breathing and going outside, even if it’s only my backyard. When I’m in my bedroom, he can hear if something drops on the tile. He’ll get up, come in here and look at me like, ‘Do you need me to get that?’ Now I genuinely want to get up every day. In a very real sense, DaVinci saved my life.”