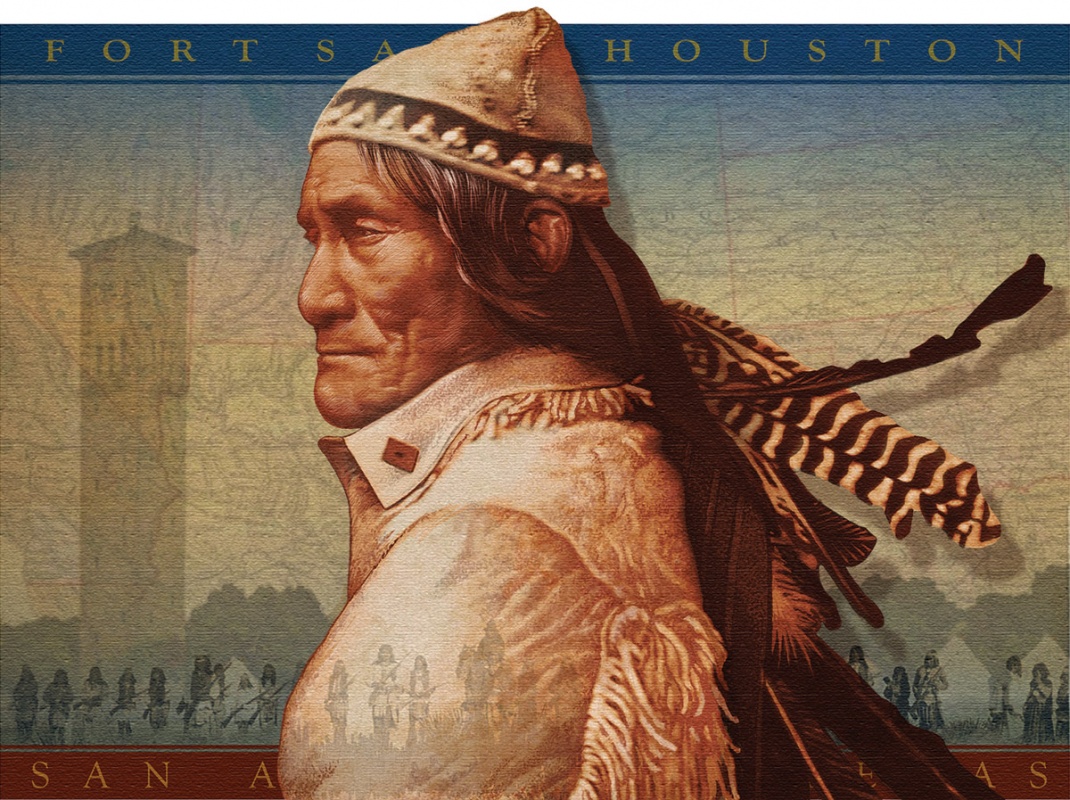

Midday, September 10, 1886, a special train from Fort Bowie, Arizona, arrived at San Antonio’s Sunset Depot. On board, under heavy guard, were prominent Apache leader Geronimo and 33 fellow Native Americans, en route to Florida as prisoners of the United States government.

Geronimo was a Chiricahua Apache who fought settlers and soldiers throughout the tribe’s homeland in what is now Arizona and New Mexico. He was a spiritual leader and formidable warrior who led the fight against settlers’ incursions into Apache lands. He had an uncanny ability to evade capture and frequently retreated into Mexico before reappearing to continue his battle.

After multiple surrenders and subsequent escapes, Geronimo and a small band of his followers, outnumbered and weary, surrendered for the last time to U.S. Army personnel September 4, 1886.

When these captives arrived in San Antonio, they were taken to the military post at Government Hill, part of present-day Fort Sam Houston, a few miles northeast of downtown. Here they were confined to the 8 acres within the limestone-walled supply depot known as the Quadrangle.

Newspaper coverage of the spectacle reflected the jingoist attitudes of the September 11 San Antonio Daily Express: “Arrival of Geronimo, Nachez, squaws and papooses—the meanest nest of cut-throats in America.” That very evening, soldiers guarded against an unruly crowd “that peered and surged and…kicked around the entrance to the government buildings,” according to the paper.

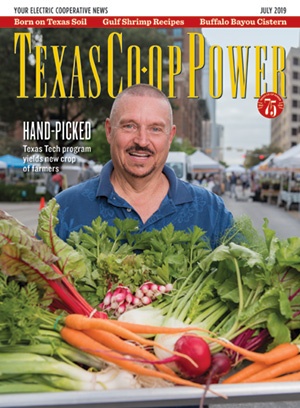

“After the Civil War, federal officials forced unrelated Apache bands to live on reservations in bleak, desolate places,” says Catharine Franklin, assistant professor of history at Texas Tech University. “Geronimo and his followers faced dire poverty, isolation, hunger and illness. It’s no wonder they fought outsiders whom they viewed as their enemies.”

Local reporters sensationalized the captives. The Daily Express described Geronimo as 50 years old, of medium height, with long black hair. His face was “seamed and furrowed” and his legs “bowed by their long grip on the saddle,” the paper reported.

“The residents of San Antonio didn’t know, and seldom cared, about the difficult choices faced by indigenous people,” Franklin says.

The prisoners were detained in the Quadrangle for six weeks while the government decided whether they were to be maintained as prisoners of war or returned to civil authorities in Arizona anxious to try them. During this time, local newspapers criticized the military officers for their leniency with the captured Apache.

The prisoners were housed in tents pitched on the lawns of the Quadrangle campus. The San Antonio Daily Light reported that they were fed “with all the luxuries of the season, fresh fruit included.” They passed time playing cards and were allowed visitors. Geronimo was driven on at least one carriage ride and “shown the city and its surroundings.” The women were granted a shopping excursion to “a store on the Plaza in San Antonio…[where they] bought all the red calico in the shop” and posed for photographs in front of the building.

On October 22, the captives were sent to join their fellow Chiricahuas in Florida. Geronimo and his warriors were detained at Fort Pickens, and the women and children were sent farther east to Fort Marion. Large numbers of Chiricahua died in Florida from disease and the tropical humidity. The survivors were eventually relocated to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where Geronimo died in 1909 from pneumonia after a horse-riding accident. He is buried in the Apache cemetery there, never having been allowed to return to his homeland.