One night in 2024, a couple traveling a Panhandle highway couldn’t avoid hitting a coyote that darted in front of them. The animal was alive but wedged in the car’s grille.

After the couple called 911, the sheriff, fire department and Texas Highway Patrol all responded. They could do little more than use their vehicles to shield the car until a wildlife rehabber arrived and carefully removed the injured animal.

It had sustained a minor pelvic fracture and a broken hind leg, which required surgery. But the coyote made a full recovery and has since been released—thanks to a village of kindhearted people, including the team at Wild West Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Amarillo.

We’ve all had our encounters with wildlife.

Maybe a bird just flew into your patio door and fell to the ground, looking dazed. Or maybe you discovered a tiny spotted fawn nestled among the zinnias in your flower bed. Did your dog bring you a gift of a baby bunny?

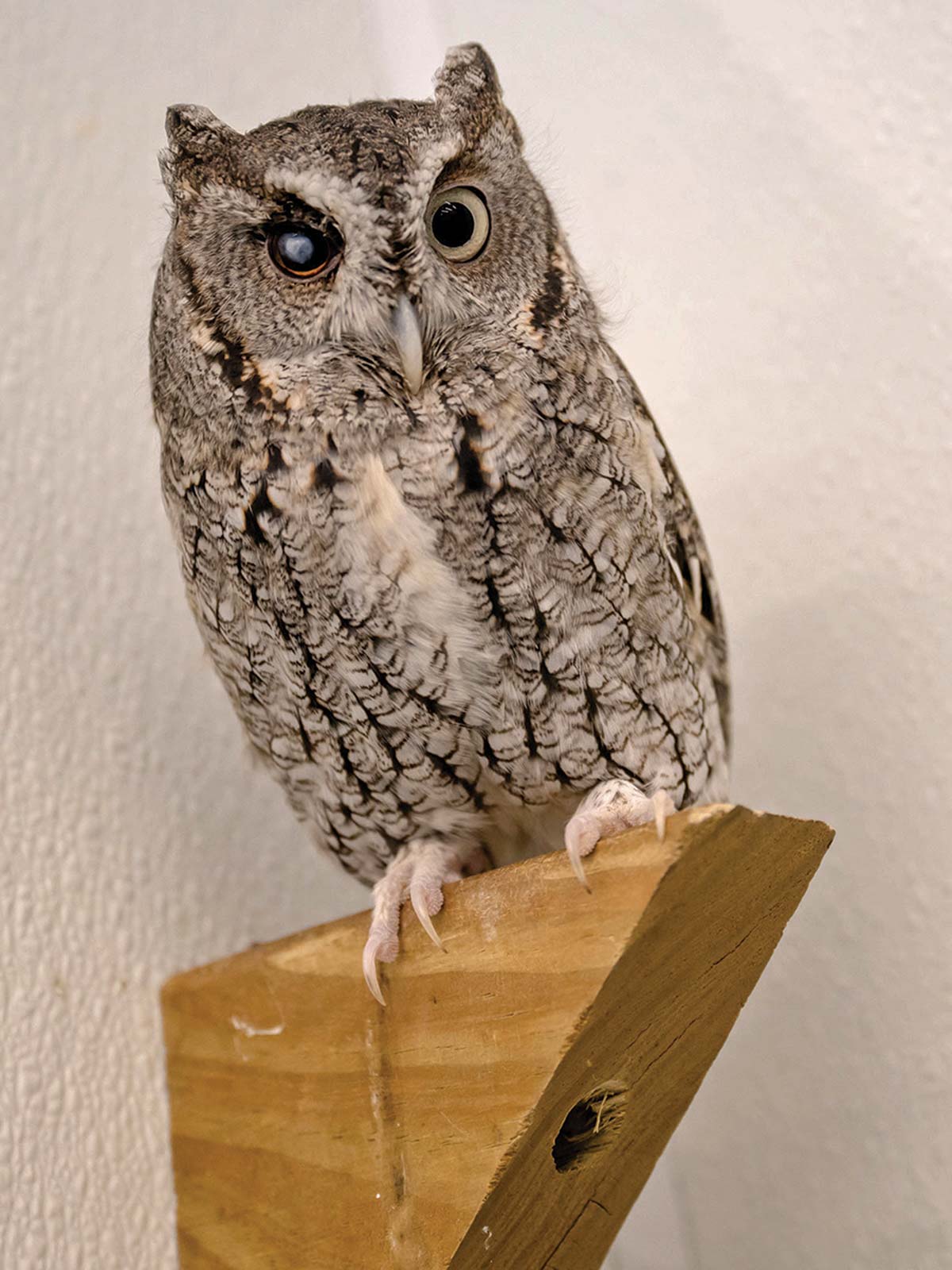

Captain Jack, an Eastern screech owl, is a permanent resident at Wild West Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Amarillo. He can’t be released into the wild because of his limited vision.

Tiffany Hofeldt

Polly is a badger who refuses to return to the wild whenever staffers release her.

Tiffany Hofeldt

If so, passionate and knowledgeable people scattered around Texas know just what to do.

Wildlife rehabilitators are folks with big, soft hearts. They’re volunteers who do not receive a single dime for their work and spend countless hours administering special diets and medications, most of which they pay for themselves. Wildlife rehabilitators cannot legally charge for their services, relying instead on donations and fundraising. Their reward comes when a recovered animal returns to its place in the natural world.

A recent Texas Parks and Wildlife Department study found that 40% of fawns brought in for care were actually uninjured and an even larger percentage of baby birds are “kidnapped” by animal lovers who are only trying to help.

DJ (last name withheld to protect her privacy since she works out of her home) has been licensed since 1999 and owns a rehabilitation facility in North Texas. Her whole family helps out with critter care.

“I have paid my kids in popcorn and Popsicles to go out and capture grasshoppers, june bugs or moths for the insect-eating animals in our care,” DJ says with a laugh.

Stephanie Brady, the director at Wild West, holds Magee, a skunk who serves as an ambassador for the facility.

Tiffany Hofeldt

A 3-month-old bobcat that was part of a litter of five abandoned by their mother and awaiting release.

Tiffany Hofeldt

She cautions fellow Texans.

“If someone finds wildlife on the ground,” she says, “I tell them to observe it from a distance first. If there is obvious blood or the animal is weak, it probably needs help, but if it is sitting normally and is bright-eyed, it’s best to leave it alone.”

Some baby birds leave the nest as fledglings and hop around on the ground, where their parents continue to feed them for several days before they take flight. Fawns are stashed somewhere safe by their mothers, who will return at dusk to feed them.

In Texas, as in almost any other state, wildlife rehabilitators are required to have state or federal permits issued by the TPWD and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Applicants in Texas must complete training and submit a letter of recommendation from a licensed wildlife rehabilitator or veterinarian. The TPWD website lists 160 licensed rehabbers across the state.

DJ lives with dozens of animals she has taken in plus her children, several of them adopted. Some of these children have been through their own traumas.

Stella, another ambassador, is a Virginia opossum raised by humans.

Tiffany Hofeldt

A gray fox named Lincoln has bonded with Brady.

Tiffany Hofeldt

“Kids who have survived trauma and then help with hurt or orphaned animals find that these rescue efforts are therapeutic and beneficial to their own normal trauma responses,” DJ says. “Our entire family pitches in under my supervision to help with caring for the animals and with the rewarding moments when they spread their wings and soar again.”

Since she has children at home, DJ doesn’t rehabilitate animals at greater risk to contract rabies, such as bats, coyotes, foxes, raccoons and skunks. One of her main concerns for wild creatures is damage done by insect spray and rat poison, which can end up killing or injuring beneficial animals, such as songbirds and owls.

Haley Caswell, general manager of Buck Wild Rescue in Ingram, has been overrun since the catastrophic flooding there in July 2025. The small clinic has outdoor enclosures, and the owner, Katie Buck, lives on the property so someone is always there.

“One of the greatest challenges we face in rehab is determining an animal’s true need for help, pertaining mostly to baby animals,” Caswell says.

Another challenge is people who hurt themselves trying to help an animal.

Jessica Hammonds cuddles Polly, who came to the center from Oklahoma.

Tiffany Hofeldt

A litter of bobcats discovered in a shed that was being torn down.

Tiffany Hofeldt

“The first thing someone should consider if a wild animal needs help is personal safety,” Caswell says. “Wildlife can carry zoonotic diseases and may pose a risk of injury through bites, kicks and scratches. Some general signs to look for are parasites, animals covered in bugs and symptoms of dehydration—dull/dry fur, wrinkled skin and emaciation. If a baby animal has been picked up by a dog or cat, we always recommend bringing it [baby animal] in for antibiotics.”

Buck Wild is one of few rescues licensed to take in and rehabilitate most types of wildlife. They serve several counties spanning hundreds of miles. Each year they take in hundreds of orphaned, sick and injured critters, providing them with a safe environment and around-the-clock care. They also care for surrendered pets, which are kept separate from wildlife.

All donations go directly to animal care; they have no paid employees. Buck Wild requires three shifts of volunteers each day to meet the needs of their animals. They strive for minimal human contact with wildlife to ensure successful integration back into nature.

“Every species has different milestones through our rehab program,” Caswell says, “from the hand-feeding incubator stage, to an intermediate weaning enclosure, to a fully outdoor enclosure where we ensure it has met the species-specific requirements of self-sufficiency.”

Wild West in Amarillo was formed after founder Stephanie Brady rehabilitated over 200 animals in five months. Her 17 years of experience as a veterinary technician led her to realize that a home-based operation would not be big enough to handle the demand.

Brady plays with Walter, a nutria from Houston. Because nutria are an invasive species, he won’t be released into the wild.

Tiffany Hofeldt

In 2016, a donated double-wide trailer on 5 acres made it possible for her to open the first wildlife rehabilitation center in the area. The venture has grown like broomweeds in a wet Texas spring. In 2024, with the help of 51 volunteers, Wild West cared for 3,128 wild animals—porcupines, coyotes, bobcats, a marmoset, and countless other mammals and birds.

“All rehabilitators are in constant need of medications, species-specific formulas, feeding syringes and nipples, blankets, towels, and further training,” Brady says.

Caring for wildlife is an endless challenge, and unlike pets, they don’t necessarily show appreciation for your help or love you back. It’s a one-sided labor of love with nature’s wild creatures.

“Releasing wildlife is altruistic,” DJ says. “Your patients bite, scratch, vomit and poop on you in thanks, but the soar, the hop, the scramble and climb away is life-giving to the world we want to gift to our children. After all, this is God’s world.”

Lincoln had been raised by Midlanders who found him in a pipe.

Tiffany Hofeldt

The Wild West Wildlife Rehabilitation Center started in a small trailer and moved into a larger new facility in 2024.

Tiffany Hofeldt