Eric Hequet grew up eating fresh-picked tomatoes bought at farmers markets near his home in Paris, France. To this day, he can still taste their juicy goodness, topped with a drizzle of olive oil and a dab of salt. Fast forward to where he lives now, and shopping for vegetables at big-box grocers makes him grimace.

“Many tomatoes today don’t have a true tomato flavor,” says Hequet, chairman of the plant and soil science department at Texas Tech University in Lubbock. “They’re round and red like tomatoes, but they’re tasteless because they’ve been bred to be hamburger-friendly. That means they have a long shelf life and very little juice so they won’t get a bun wet. Unfortunately, fruits and vegetables with little to no taste are common in the marketplace.”

To change that, Hequet, an award-winning researcher in cotton genetics, led efforts to establish a new undergraduate degree specialization at Texas Tech for 2018. The new program allows students to focus on local food and wine production systems.

A class in a Texas Tech University vineyard weighs pruned clippings.

Wyatt McSpadden

This study concentration, the first of its kind in Texas, will prepare students for farm-to-table careers, such as an urban farmer, orchard manager, crop consultant, winery cellar master, or fruit and vegetable marketing specialist.

Such forward thinking has kept Texas Tech at the cutting edge of ag education. In 2010, motivated by the rapidly growing wine industry in Texas, the university established the state’s first viticulture and enology degree program. The new local food and wine production program is a response to an increasing demand for fruits, vegetables and other edibles produced by small farms using earth-friendly practices. According to one report published by Packaged Facts, a source of market research for the food industry, local foods generated $11.7 billion in sales in 2014 and are predicted to reach $20.2 billion this year.

What makes a food “local”? It depends on whom you ask. “Locavores,” a term coined in 2005, encourage people to eat food grown within 100 miles of home. But under the 2008 Farm Act, a product may be considered local if it’s shipped within the same state or less than 400 miles from its origin. Consumers want more.

But given food producers’ thinning ranks, who will produce that local food? In the U.S., more than 31% of farm operators were 65 or older in 2012, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Texas Tech University officials hope that an ag degree with a focus on small-scale farming will entice more young people into the field.

“Cotton production is very important around Lubbock,” explains Hequet, who researched cotton fiber technology in Africa and France before joining Texas Tech in 1997. “However, a young person lacking an ag background or family in the business can’t spend millions of dollars to get started in growing cotton. It’s impossible.

“However,” he adds, “they could buy a few acres and grow high-quality vegetables for sale to restaurants and high-end stores in the city.”

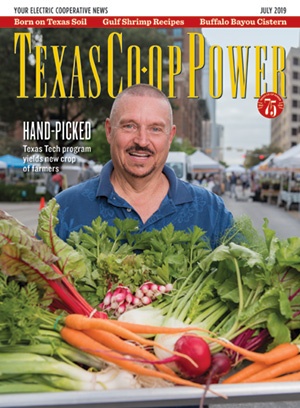

Fennel and beets for sale at the Sustainable Food Center’s farmers market in downtown Austin.

Wyatt McSpadden

Hequet stresses the importance of introducing city kids—not just the sons and daughters of row-crop producers—to agriculture. He suggests that growing fruits and vegetables to feed local markets is more appealing and more marketable, because of the growing urban agriculture trend.

Hill Country Campus

The local food and wine production program, which kicked off in fall 2018, enrolls students both in Lubbock and at Hill Country University Center in Fredericksburg. Texas Tech partners with several Central Texas colleges so students can seamlessly transfer credits. Ed Hellman, a viticulture and enology professor at Texas Tech since 2000 and member of Central Texas Electric Cooperative, moved from Lubbock to Fredericksburg to oversee the program, which could expand to encompass animal products.

“Our program is unique in that we include wine because it is such an important component of the farm-to-table movement,” Hellman says. “The local wine and food connection is really strong, especially here in the Hill Country. Human connection is another driving force. It’s reassuring to people to know that their food was grown or made with care by someone local they can talk to.”

Under Tech’s new program, coursework focuses on the sustainable production of fruits and vegetables and introduces students to wine science, grape growing, wine marketing and hospitality management.

“The business of local production is not just about growing crops but working with wineries and restaurants to enhance their customers’ experience with the best local products,” Hellman notes. He explains that the program emphasizes sustainable practices, which use products and methods that are considered to be safer for the environment but still economically feasible.

Nelson Avila, a Lufkin native who completed most of his general education classes at Austin Community College, chose to specialize in Tech’s program. At 43, he’s working toward earning a Bachelor of Science degree because he wants to make a difference.

“We’re running out of land because it’s being developed or overtilled,” says Avila, who paints houses in Austin to help pay his family’s bills. “The world is growing, and people need to eat. I want to grow sustainable crops on a small farm and teach my kids how to care for the land.”

Richard Ney, front, and Alik Hovhannisyan of Texas Food Ranch near Fredonia sell their produce 100 miles away, at the Sustainable Food Center’s farmers market in downtown Austin.

Wyatt McSpadden

Central Texas EC member Richard Ney and his partner grow a selection of vegetables, fruits and berries on the Texas Food Ranch, their property near Fredonia, 100 miles west of Austin. They practice what the Texas Tech program teaches students, and Ney underscores the importance of the small producer. “People want to know their farmer,” Ney says, “so they know the vegetables are not pumped full of chemicals.”

Move Over, Peaches

Two decades ago, tourists flocked to Fredericksburg for peaches, not wine. Back then, only four wineries and one wine tour company operated in the area. Today, Hill Country wine tourism is booming, and the area around Fredericksburg includes more than 50 wineries and 18 tour companies.

1851 Vineyards wine is produced by Dabs and John Hollimon, recipients of Texas Tech viticulture and winemaking certificates.

Wyatt McSpadden

“Peaches are still important, and they still are a driver in the local farming and agritourism industry, but vineyards and wineries are now leading through sheer numbers,” says Jim Kamas, associate professor and extension specialist with Texas A&M AgriLife in Fredericksburg. “With that, peach grower demographics are changing. They’re getting older, and they’re wanting to grow fruit crops on a smaller scale that emphasize quality over quantity.”

Toward that goal, Kamas, a member of Pedernales Electric Cooperative, evaluates pears, figs, raspberries, blackberries and pomegranates at the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Viticulture and Fruit Lab near Gillespie County Airport. He also helps small producers identify varieties of specialty fruit crops uniquely suited for their local markets.

Alternate Schooling

Food producers and people wanting a career change can get a boost from professional certificate programs earned through Texas Tech. The two-year viticulture certificate program, which started in 2008, has graduated 177 students, many of whom have started their own vineyards and wineries. Since 2014, the two-year Texas winemaking certificate program has awarded 53 professional certificates.

In the near future, the school plans to offer a small-scale farming course on sustainably producing fruits and vegetables for local markets. All certificate programs are a mixture of online classes and hands-on sessions in Fredericksburg and Lubbock. For example, viticulture students plant and propagate grapevines at the on-site vineyard at the Hill Country University Center.

“For doctors, lawyers, engineers and other people who don’t want to go back to college, our continuing ed programs allow them to get up to speed,” Hellman says. “Many of our students want to work at a winery, but they don’t want a college education. This is a way for them to get an education without the full commitment and cost.”

Dabs and John Hollimon, who own 1851 Vineyards near Fredericksburg, earned viticulture and winemaking certificates through Texas Tech.

Wyatt McSpadden

Dabs and John Hollimon, who own 1851 Vineyards, south of Fredericksburg, respectively earned a winemaking and viticulture certificate. With help from their grown children, they resurrected a vineyard that Dabs inherited. In 2013, they planted 600 grapevines followed by 5,000 more the next year. Five years later, their medium-sized winery has an annual capacity of 10,000 cases of bottled wine.

“Our 2016 Estate Tannat was a double gold winner in the 2019 San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition,” says Dabs, a retired schoolteacher and member of Central Texas EC. “That’s a lot of validation for what we’re doing with our grapes and winemaking. We couldn’t make the quality wines that we do if we hadn’t taken the Texas Tech courses.”

Their 1851 Vineyards label is among more than 25 Texas winemakers carried at the Cabernet Grill in Fredericksburg. Since 2006, chef Ross Burtwell has offered a Texas-only wine list, which he combines with locally sourced ingredients to create what he calls his Texas Hill Country cuisine.

“As they say, what grows together goes together,” says Burtwell, a member of Central Texas EC. “It’s fantastic what Texas Tech is doing. We’re facing a labor shortage, and to be able to hire passionate people who are knowledgeable about local food production will be great for our industry.”

Sheryl Smith-Rodgers, a member of Pedernales EC, lives in Blanco.