“Dad tried to make a cowboy outta me, but I never had the natural talent it took,” legendary Western writer Elmer Kelton told me recently at his home in San Angelo. “I just wasn’t as good at it as I oughta been. I wanted to be a cowboy, but it just wasn’t there. One thing was I was nearsighted and it took a long time to figure that out, so I’d go out and couldn’t see the men on either side of me and fall behind and mess up the drive.”

Kelton’s father, Buck Kelton, was the foreman of the McElroy Ranch, a 230-square-mile spread overlapping Upton and Crane counties in West Texas. When it came to cowboying, Buck sometimes said his son was “as slow as the seven-year itch.”

“That gave me an inferiority complex, for sure,” Kelton said. “I was always out there trying, with the cowboys who were so adept at what they did, and my younger brothers coming along—they were all better hands than me. I always felt a little out of place wherever I was. When I was with the cowboys I wasn’t at their level, and in town I was regarded as a cowboy, not a town boy.”

Soon after he discovered he was nearsighted, tuberculosis confined Kelton to bed for almost a year. He’d always been a “bookish kid”—“Very often I beat the girls at spelling bees,” he said—but while ill, his bookishness flourished.

“That inferiority complex pushed me further toward the creative work,” he says. He read and drew and made up stories and sketched mock-ups of newspapers on notebook paper, crafting news columns and headlines about ranch affairs.

He returned to ranch work after he got well, but “the die had already been cast to some degree,” he says. “There was just a natural weaning process that went on.” He would become a cowboy writer, he realized, and not a cowboy. “But writing seemed kind of a sissy thing,” he said, “so I didn’t boast about it.”

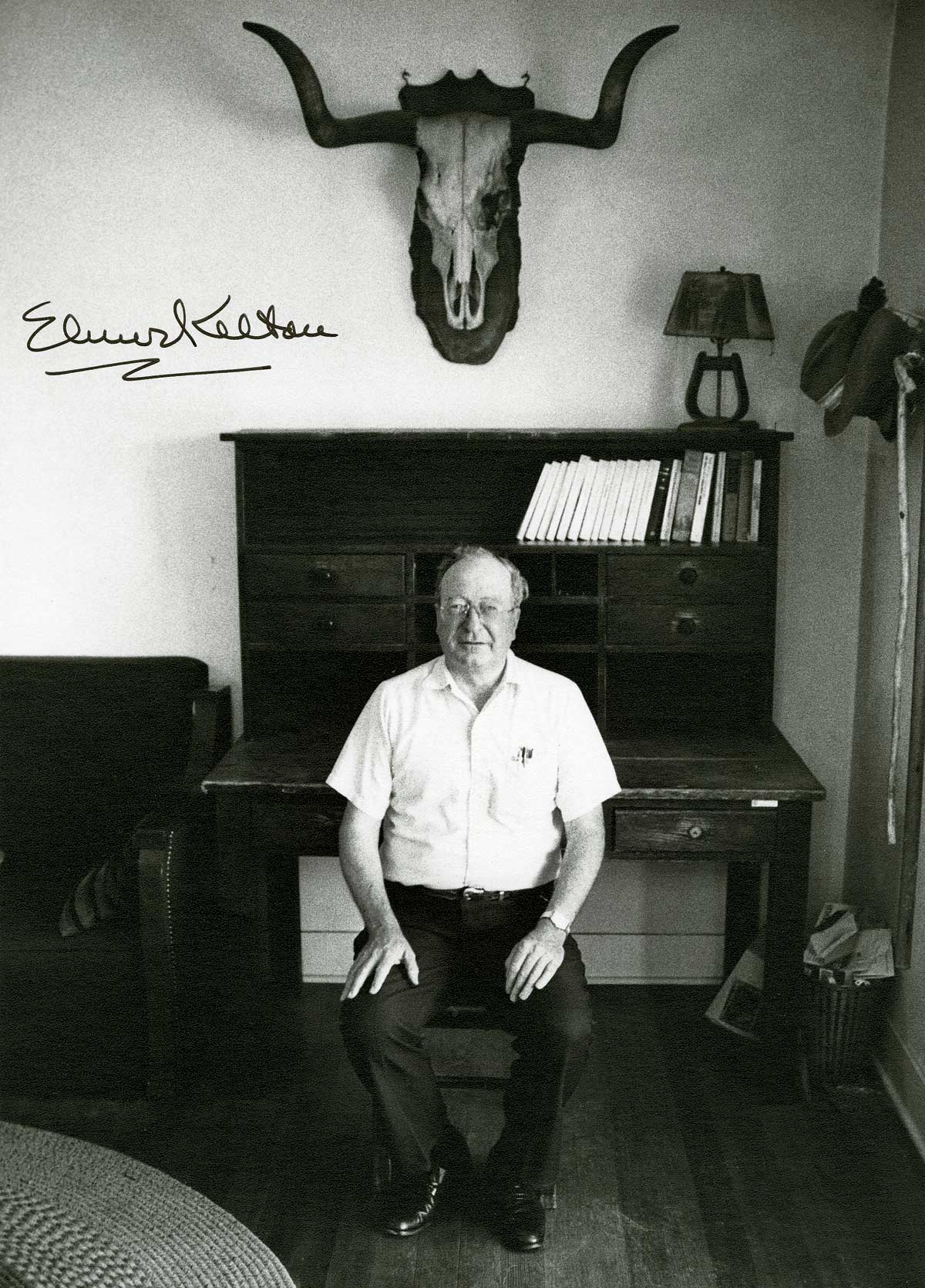

Kelton lives with his wife, Ann, an Austrian whom he met in Ebensee, Austria, while serving in World War II in the U.S. Army, in a brick, ranch-style home on a quiet street near the groomed campus of Angelo State University. They have supplied their thick-carpeted living room with prints of Western scenes, bronze statuettes of cowboys on horseback and porcelain Austrian villagers in holiday costume.

“It’s like a museum,” Kelton said, “and we’re gettin’ to be museum pieces.”

Elmer Kelton is 83 and quiet-looking. He is neither tall nor wide. He wears glasses with large, round lenses and favors plain, snap-button shirts. His conversation is relaxed.

Kelton has almost finished his 51st novel, Other Men’s Horses, which is scheduled for publication this fall. Several of his books, including the novels The Time It Never Rained and The Day the Cowboys Quit, are considered classics of the genre and notable works in American fiction.

Kelton has won just about every Western writing award there is, including seven Spur Awards from the Western Writers of America, which in 1995 named him the greatest Western author of all time. The annual Spur Award represents the finest in literature about the American West. Four of Kelton’s books have won the Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

In his life and work, Kelton has stayed close to his original vision of himself, to the particular cowboy lifestyle into which he was born but not fully bred. He left Crane County to get a journalism degree at the University of Texas, then returned to ranch country as a farm and livestock reporter for the San Angelo Standard-Times—a professional observer of his past. He left the Standard-Times after 15 years to edit Sheep and Goat Raisers’ Magazine and then became associate editor of the Livestock Weekly. Until he retired from that publication in 1990, he was a moonlighting novelist, fictionalizing much of what he reported. “Do you know there’s someone out there with your name writing Westerns?” a subject once asked him.

Kelton has written many pulp westerns—he got his start in college in the 1950s, composing stories like “His Gun Was the Law” and “Blind Canyon” for magazines like Ranch Romances and Thrilling Western—but he has steadily moved away from formulaic writing toward literary work.

“I feel that progression, I sense it when I look at all my books,” he says.

Kelton’s best novels are minutely naturalistic, sparely plotted and meticulously sociological—devotional portraits of ranch life in West Texas. In them, he attends to the sensory effect of machinery (“The steel windmill pumped a small gush of water into the concrete tank with each clanking stroke of the sucker-rod”), conjures the hellishness of unending weather dependency, and reconstructs racial and economic hierarchies. His readers watch, at sheep-shearing time, as fleeces “fold away from the animal’s body and expose the bright cream color of the inner wool”; they see how raindrops striking desiccated soil fail to soak in, but instead “swirl and run away, following the contours of the land, seeking out the draws and swales”; and they learn that a rancher low on feed will burn the spines off prickly pear cactus by making “a slow, gentle pass with the flame,” allowing the thorn “to burn back to a stub without the pear itself having time to singe.”

Representations of ranch life are everywhere in Kelton’s home. The mantlepiece shelf is taken up by five bronze cowboys on horseback, a bronze cowboy holding a coiled lariat and a bronze cowboy holding a saddle. These are awards from the National Cowboy Hall of Fame, the National Cowboy Symposium and the Western Writers of America.

Yet another mounted cowboy statuette sits on a columnar coffee table that functions as its plinth. On its base, a nameplate reads:

“Keepers of the Heritage”

with Elmer Kelton

I was surprised to learn that the sculpted cowboy on the horse was Kelton himself.

Kelton would never confer the term “real working cowboy” on himself, but for two summers he was. Buck Kelton had his own cattle operation, the Lea Ranch, on 20 square miles of leased land adjacent to the McElroy Ranch. After Elmer’s junior and senior years in high school, Buck asked him to manage it. Kelton was the only full-time hand; his three younger brothers took turns coming out to help.

The work was simple. Kelton rose at dawn and fixed biscuits and coffee. He brought in the work horses and saddled his favorite. He rode the length and width of the ranch, inspecting fencelines and windmills, checking cattle for screwworm and painting disinfectant where he found blowfly bites. If a fence was broken, he’d get tools and wire from the house and bring them back in a wagon; if a windmill was broken he’d go get the McElroy’s windmiller, Cliff Newland. He was on a horse all day. Without trying, he memorized the landscape.

For dinner, Kelton and his brothers ate canned red beans and fried steak—beef from their father’s herd. For variety, they trapped and roasted quail. They swam in the ranch’s stock tanks, raced horses and shot jackrabbits for practice. On a hand-crank phonograph, they played Bob Wills, Gene Autry and the Sons of the Pioneers. By the light of a kerosene lamp, Elmer Kelton read The Ox-Bow Incident and Tombstone.

What chiefly occupied Kelton’s mind those summers were the weather, the wildlife and the progress of the seasons.

“They were probably the freest times I ever had,” he said. “I’d have been content to stay out there forever.”