At their core, all cooperatives—regardless of type—exist to meet the needs of their members and the community. Bearing that in mind, Big Country Electric Cooperative entered into a partnership 10 years ago with the Development Corporation of Snyder and Western Texas College to establish the school’s electrical lineman technology training program.

Expecting to be affected by a nationwide retirement rate of 25% among trained lineworkers in the near future, co-op leadership knew the time to train replacements was upon them. DCOS provided supportive financing to bring the idea to life, and WTC, with its vocational education expertise, sought industry guidance to develop the curriculum.

When the first class graduated, other electric co-ops and utilities took notice. Ten years and 158 graduates later, the program is thriving and turning out lineworkers who have a solid grasp for building and maintaining reliable electric systems. “Of course, we’re a bit biased to its importance, but it really is a great program,” said Dr. Barbara Beebe, president of WTC. “The success of the students in the program has enhanced WTC’s reputation as a provider of quality career and technical education programs. The program has provided a wonderful opportunity to partner with industry to provide much needed specialized training in the West Texas area. Our partnership with Big Country Electric Cooperative has been a win-win for our students, the college, and the industry.”

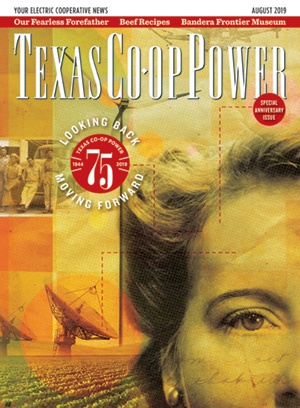

2019 marked not only the 10th anniversary of the program but also the enrollment and graduation of the program’s first female student, Allegra Escobedo. Eighty years ago, when rural electrification spread across the nation, female lineworkers were unheard of. But over the past few years, women—who hold their own in a field largely dominated by men—have joined the ranks, proving that they can do the job, too.

Allegra Escobedo, the program’s first female student, shows curious onlookers that she has what it takes to be a lineworker.

“I did my basics at WTC, but the college route turned out to be something I just wasn’t that interested in,” Escobedo said. “I talked to [program graduates], plus I like to be busy and do hands-on work, so I decided to give it a shot. I was really nervous my first day because, believe it or not, I was afraid of heights. The first day of class [instructor Frank McLen] had each of us climb to the top of a pole. After that, I was fine.”

Parents, loved ones and friends of prospective lineworkers are often guarded in their support of the career choice because of its ever-present dangers. “My dad was probably the most hesitant, my friends were a little nervous, but my mom was excited—and I surprised them all,” Escobedo said.

So what is it like to work as a woman in a field dominated by men?

“Honestly, it pushes me to up my game,” Escobedo said. “Some things were harder because I am a girl, but the guys all helped me and made me feel comfortable. The atmosphere was competitive but supportive. We would split into groups and have races up and down the pole—that pushed me to do my best. I’m looking forward to climbing,” she continued. “I want to be outside doing work—not inside.”

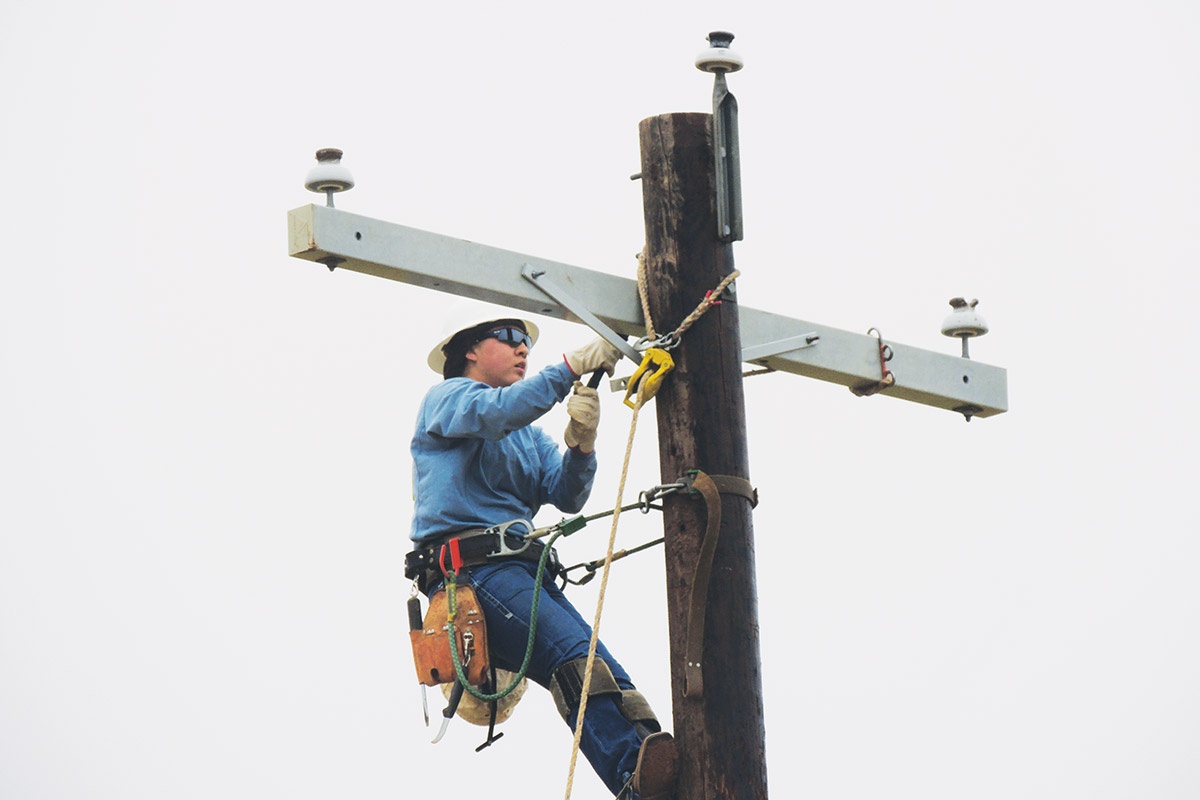

Par for line work, students of Western Texas College’s electrical lineman technology program took to the poles on a rainy day in May to showcase their skills for potential employers.

McLen, a seasoned lineworker with more than 25 years’ experience, had the same expectations of Escobedo as every other student. “I didn’t cut her any slack—none at all,” he said. “I required from her the same thing I required from every male student, and she met every one of those expectations. I was concerned about having a girl in a man’s working environment, but she proved that was not an issue.”

In May, at the program’s capstone performance, an annual showcase where students demonstrate their skills for utilities looking to hire lineworkers, curiosity was rampant about how Escobedo would do. She did great, as did her 17 male counterparts.

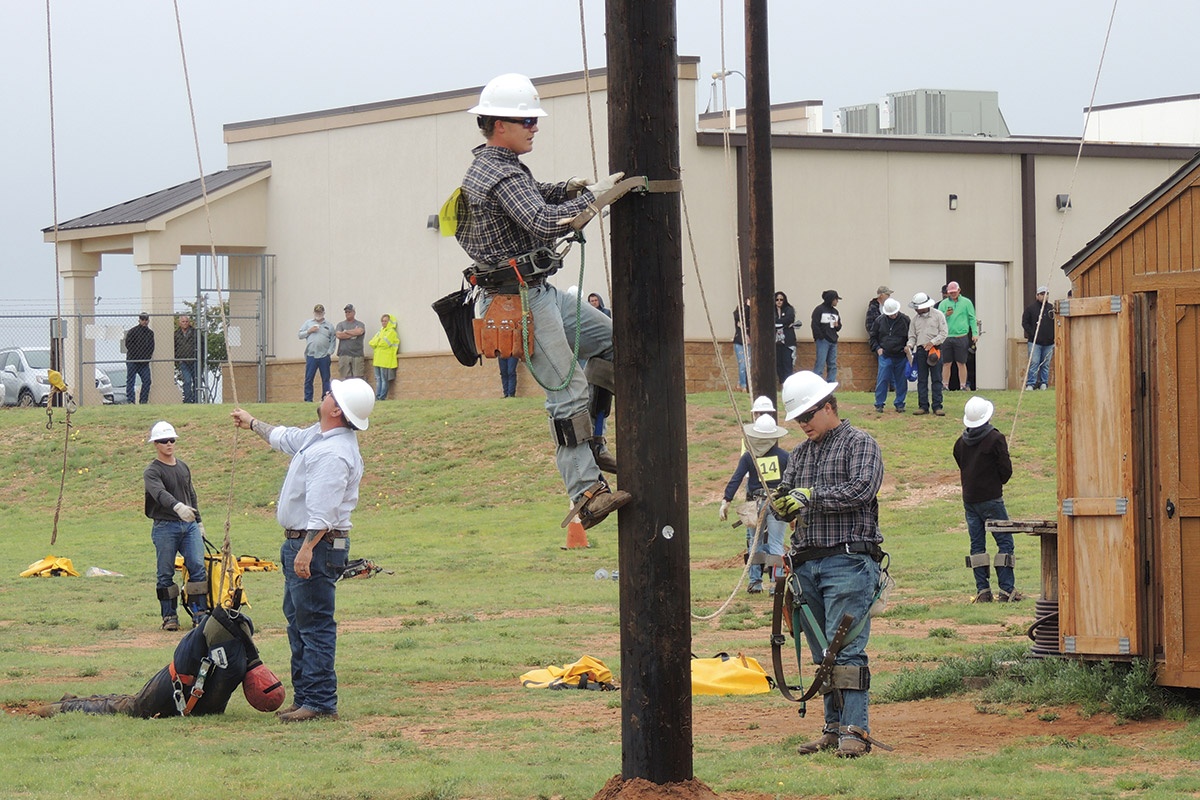

Twins Dustin Kiser, on the pole, and Justin Kiser, right, worked as partners for the showcase. Instructor Frank McLen, left, assists another student with a hurt-man rescue.

At each showcase, the job offer rate is almost 100%: Nearly every student since the program’s inception has graduated with at least one job offer, which come from a host of utilities that attend the capstone performance, including BCEC and other co-ops from Texas and Oklahoma, investor-owned utilities and contractors who come from all over the map. Lineworkers are in demand, and they have a wide range of options.

Chris Ward, a program graduate and journeyman lineman, has traveled to Puerto Rico for storm restoration after a hurricane and to California after the devastating wildfires earlier this year. Gabriel Vasquez, a graduate of the first program cohort and construction foreman, was hired by BCEC upon graduation and has progressed through the ranks, holding third-, second- and first-class lineman positions before achieving journeyman designation, which denotes mastery of the trade.

“Being a lineman has been great for me and my family,” Vasquez said.

Line work isn’t all about pole-top work—help on the ground is essential to the safe and efficient execution of overhead work. Here, Jarryd Karr runs a handline between the ground and a fellow student, working above.

“We have received nothing but positive feedback back from employers,” shares Beebe. “Many have commented that when our students graduate from the program, they are well prepared for positions in the industry. The nearly 100% placement rate of our students, most graduating with multiple employment offers, highlight our student and program success. Feedback from graduates has been very positive. Many have remarked that it was a great opportunity to have been able to participate in the program. One student in particular even commented that the program literally changed his life! Annual applications to the program routinely exceed available spots. The program has also been well received by the community, making it one of WTC’s most popular offerings. WTC is proud to be able to positively impact the lives and the futures of our students.”

Thirteen of BCEC’s current employees are graduates of the WTC training program, and of those 13, four are crew foremen, two are first-class linemen, and three are young, newly hired and possess great potential to move up and train another generation in turn.

Despite the rapid evolution of technology in the field, linework is as tough now as it has ever been. “It’s still a very physical job, but there’s a lot more equipment now than when I started my career,” McLen said. “Bucket work is the norm nowadays, so being able to climb well makes a lineworker stand out in this field now. I try my best to teach these students the fundamentals of climbing so that they can do their job no matter the circumstances.”

If a location is particularly muddy, for example, using a bucket truck isn’t an option. “I run my class as lifelike as a real job,” McLen said. “Our curriculum is defined but prone to change because that’s the reality of line work—it can change on a moment’s notice.”

BCEC apprentice lineman and 2018 WTC program graduate Sean McClure helps with a hurt-man rescue.

On a moment’s notice and over the past 80 years, electric co-ops have weathered an exponentially changing world. Change is what line work is all about: It developed out of a desire for and as a result of technological change, has spawned more changes and will continue to evolve along with the needs of the industry.

If Rosie the Riveter could do a man’s job almost 80 years ago, then Rosie, Allegra or anyone who heeds the call can be the face of change that leads line work into the future.