When Danny Williams started his career as a lineworker at McCulloch Electric Cooperative in 1965, color TVs were the latest marvels coming into homes.

Danny and his co-workers at the Brady co-op—which no longer exists—made sure the power always stayed on for those TVs.

“I loved linework,” he says. “I loved climbing.”

Danny later became an instructor, teaching work skills and safety to utility employees. And in 2007 he became manager of Texas Electric Cooperatives’ Loss Control program, where he changed lives at co-ops across the state.

“Danny Williams has a passion for helping others like I’ve never seen before. It’s personal,” says Mike Williams (no relation), TEC president and CEO. “He has helped make this Loss Control program the best in the nation.”

Danny Williams, 80, will retire this month after more than 38 years teaching generations of lineworkers the right way to come home from one of the most dangerous jobs around.

It’s “the retirement of a legend,” says Wesley Caldwell, a regional supervisor in the Loss Control program and one of 10 instructors who work for Danny. “He’s made a big commitment to changing the culture at every co-op he’s ever called on.”

Tami Knipstein has worked closely with Danny for 17 years. As the Loss Control program’s coordinator, she keeps the staff’s calendar straight and helps ensure that when a co-op needs training, the team can make it happen. “Danny puts his heart and soul into training because he wants all linemen to return home to their families after working one of the most dangerous jobs there is,” she says.

Tears trickle down Danny’s cheeks when he thinks about his work life, which started long before his co-op days in the 1960s.

“I’ve been working since I was 8 years old,” he says. “Don’t know anything else.

“My family was poor. Very poor. We didn’t have nothing.”

His dad bought him a push lawn mower and sent him down the street, giving the family another needed breadwinner.

“And I walked around Brady when I was 8 years old—to help the family,” he says. “I was a little fat, chubby kid, and them old ladies liked me. And I mowed lawns and paid for that lawn mower.”

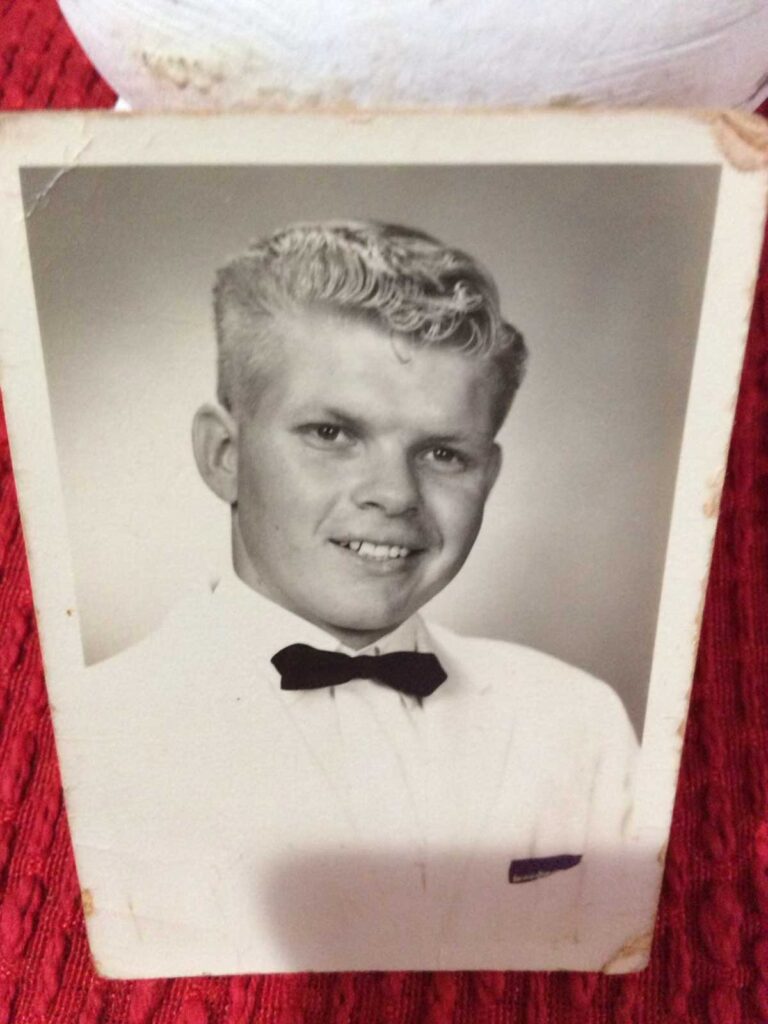

Danny graduated from Brady High School in 1962.

Courtesy Danny Williams

Diane, Danny’s wife since 1995, says she used to help him practice his presentations as he worked to overcome his fear of public speaking.

Courtesy Danny Williams

Later he hauled hay, picked cotton and worked at a feed mill. Then he landed a plum job at the co-op.

“I went to work for them for $1.10 an hour in 1965, and that was the best-paying job in town,” he says. “I was working at a peanut mill making 90 cents an hour.”

Danny remembers that first day—January 4, 1965. There was no orientation or onboarding in those days. He showed up Monday morning and was immediately sent out with a crew.

He had no idea what he was doing.

“No, not a clue,” he says. Guidance was sketchy: “This is how you do it, and I ain’t showing you again. Tomorrow you better know how to do this.”

But he stuck it out and followed a blueprint common at electric co-ops, working his way up—from groundman to apprentice lineworker and then journeyman. Later he became line superintendent and then operations manager at McCulloch EC.

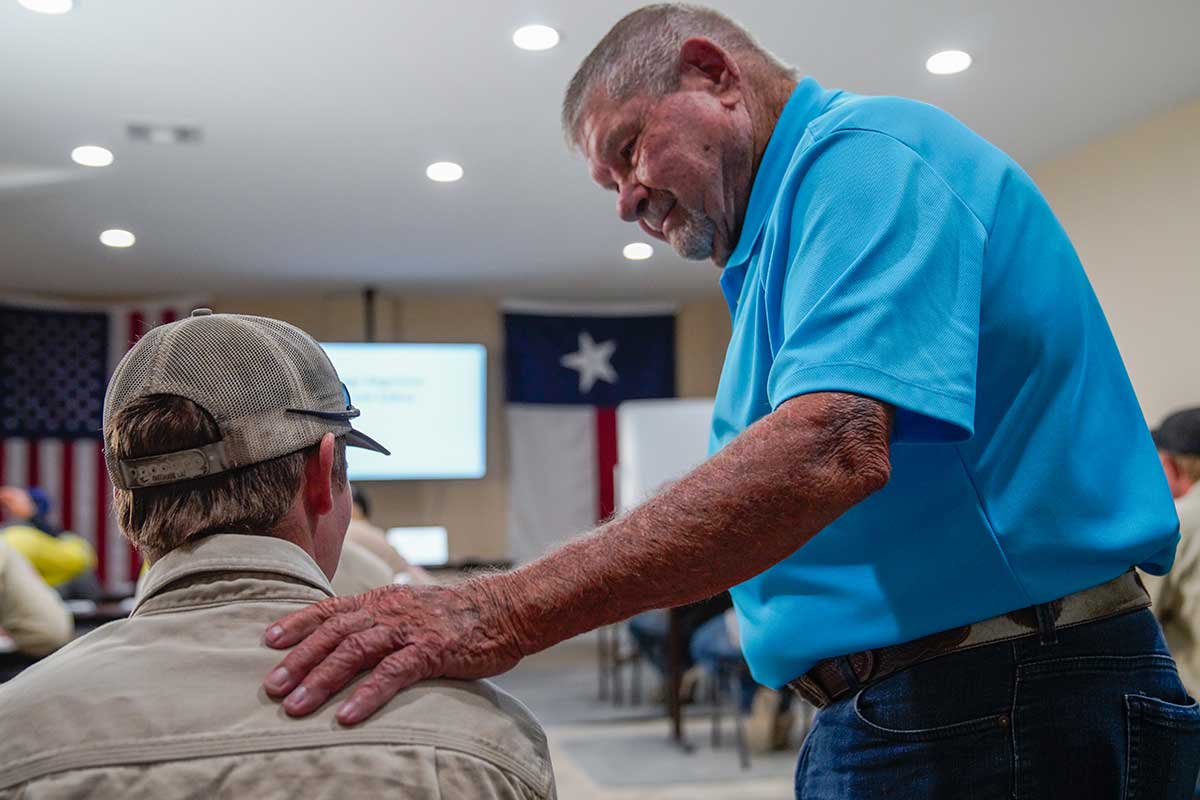

Danny says he sees lots of lightbulbs come on in the heads of students. “They’ll tell you, ‘I didn’t know that.’ I see that every day. Every day.”

Caytlyn Calhoun | TEC

“I don’t think that I picked the job,” Danny Williams says of his 59 years in the utility industry. “I think the job picked me. I still believe that.”

Caytlyn Calhoun | TEC

In 1985, Danny made a career change, turning to safety and training for the Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service. He moved to TEC in 2000 and has been underpinning the safety culture at co-ops ever since.

“Danny’s dedication to safety is unmatched. He’s kept countless people safe,” says Martin Bevins, TEC vice president of communications and member services. “Danny has made a difference in this world.”

Today Danny is known as a leading ambassador for workplace safety. “Danny peddled safety like it was a life-or-death commodity, and without a doubt, Texas lineworkers have bought in,” says Danny Nixon, a longtime friend and the operations manager at Lighthouse Electric Cooperative.

In a classroom setting or standing among students surrounding equipment at a training field, Danny Williams’ soft-spoken wisdom comes patiently. He makes eye contact, watching for lightbulbs to come on when the message lands.

“He’s the best,” says Scott Ferguson, director of cooperative services and emergency operations at Sam Houston Electric Cooperative. “He is full of knowledge. He’s done the work. He’s not just talking it. He’s on a lineman’s level. He knows the dangers.”

Safety is sometimes a hard sell, an endless challenge for Danny and his team. Convincing young men—and field work in the electric utility industry is still almost exclusively performed by men—that high-voltage electricity is hazardous and unforgiving shouldn’t be difficult, but sometimes it is. As Danny explains it, so many of them think they’re invincible.

That’s why he and his team rise before sunup to travel the state providing training and nearly a thousand safety meetings a year that teach safe techniques for climbing poles and handling every piece of equipment that keeps the power grid functional. Still, bad habits show up among even seasoned workers. So do occasional injuries—some devastating—and deaths. Power line construction is among the most hazardous occupations.

“You can teach them the right way. But you cannot watch them 24 hours a day,” Danny says. “You cannot be with them when they’re out there doing the work. When they’re out there, they make the decision [about] what they’re going to do.

“Even though they’ve been taught right, sometimes they don’t do right.”

And shortcuts can turn into imprudent habits. “You get away with it once, you’ll try it again,” he says. “Until something happens. That’s human nature—one thing we’ve never been able to change.”

He thinks back to when he was a lineworker in the 1970s, and he knows he was no different from today’s workforce.

“What I remember, after a safety meeting, I worked pretty safe for about two weeks. After that I went back to my old ways,” Danny says. “Complacency is one of the world’s worst things.”

Danny with his son Gordon, a regular traveling partner for 17 years.

Courtesy Danny Williams

For years, when Danny showed up at a utility, employees knew to expect two things: They would learn something and they would get to see Williams’ son, Gordon.

Gordon was a special traveling partner. He was born in 1963 and was soon diagnosed with Down syndrome. A doctor told Danny that Gordon wouldn’t live past the age of 9.

But well into his 30s and 40s, Gordon rode shotgun as Danny roamed the state. “He went with me 17 years on the road,” Danny says. “Everybody loved Gordon. He never met a stranger.”

In his 50s, Gordon’s health began to fail, and he died in December 2019 at the age of 56. “He taught me more about life than anybody,” Danny says.

Reminiscing about his career always takes Danny to his time with Gordon—and to his time trying to make working on the electric grid safer.

He has succeeded. He’s sure of it. Often, sometimes years later, he hears that wisdom imparted saved a utility worker from injury—or worse: “I remember what you said or what you did that helped me and kept me from getting hurt.”

That’s how he knows he’s made a difference. That those hundreds of thousands of miles behind the wheel and weeks in roadside motels changed lives. Saved lives.

“Oh, my God, how many people has he touched?” says TEC’s Curtis Whitt, a co-worker for 21 years. “Countless. To do it as well as he’s done it for as long as he’s done it is a pretty incredible feat.”

Diane Williams, Danny’s wife of 29 years, is ready to have him home for good. “Just to see him relax, take a breath and not be at the top of his game 24/7,” is her wish for his retirement.

They have moved back home, to Brady.

“I’m gonna have me a little garden,” Danny says. “Buy me a few chickens. And Brady’s got a little lake. I’ll get me a little bass boat—we’re going to fish.”

He’ll even sleep in.

“Sure, till about 7 o’clock.”