If you’re lucky, you don’t remember the asafetida bags of days gone by. If you’re one of the unfortunate few who had firsthand experience with the “assifitity” bags, as they were sometimes pronounced, the first thing you remember is the smell—and not in a good way.

Well-meaning mothers used to put asafetida, a pungent root product, in a sachet and tie it around their children’s necks, thus ensuring social distancing more than a century before the term was in use. The bags were rumored to ward off everything from the sniffles to spinal meningitis.

Asafetida, unlike many of the early settlers’ cures that came from the land, came from drug stores.

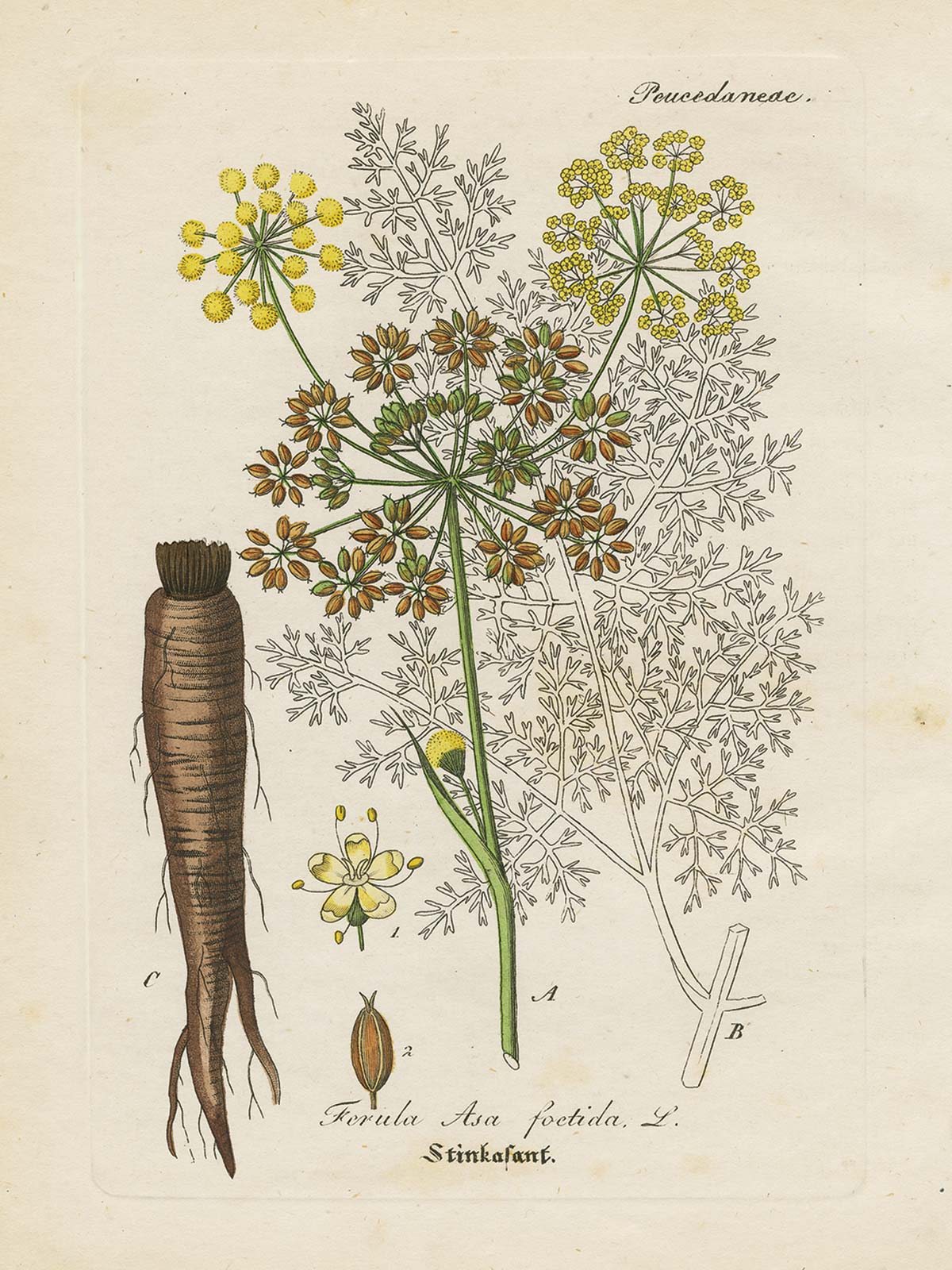

The resin is extracted from an herb called asafetida that grows primarily in Iran and Afghanistan and belongs to the same general family as carrots, parsnips, parsley and anise. The resin’s common nickname—devil’s dung—doesn’t help its reputation. The scientific name, Ferula assa-foetida, translates to stinking resin. That doesn’t help either.

Before there was a market for asafetida, there was silphium, an ancient spice that was so popular people couldn’t get enough of it. As a result, it went extinct. Alexander the Great apparently mistook asafetida for silphium during his invasion of Asia in 334 B.C., and this new herb caught on as a substitute and eventually made its odorous way to Africa and Europe.

Asafetida most likely came to America with enslaved Africans who had multiple medicinal, magical and apotropaic uses for it. They developed a tradition of wearing a red flannel bag containing the plant’s roots and additives like red pepper, sassafras and snakeroot. That became the preferred use for asafetida in this country, where the asafetida bag became a staple of health care in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Lewis and Clark even took along a pound of asafetida on their expedition of discovery in 1803. We don’t know why and there’s no record of them using it during the journey, but receipts show Lewis bought a pound for $1.

By the early 20th century, Americans would turn to the asafetida bag whenever a new health scare hit the news.

In Texas, the January 11, 1912, edition of the San Angelo Evening Standard reported that locals “have resorted to the use of asafetida bags as a precaution against Spinal Meningitis. They are wearing little bags of it around their necks, and hope to thus destroy any germs that come near them. Mothers for the past 50 years have made their children wear an asafetida bag when an epidemic of any sort of sickness prevailed.”

Dallas columnist Paul Crume, who grew up in the Panhandle, wrote in 1970 that he had no direct experience with asafetida bags because his family “leaned instead to the mustard plaster school of advanced family medicine. We preferred to hurt rather than stink.” But Crume expressed sympathy for those forced to wear the foul-smelling bags around their necks. “They felt,” he wrote, tongue slightly in cheek, “that humanity generally was turning up its noses at them.”

In 1918, the United States Pharmacopeia recommended asafetida to stave off the Spanish flu pandemic.

Today, it’s “used in modern herbalism in the treatment of hysteria, some nervous conditions, bronchitis, asthma and whooping cough,” the National Library of Medicine notes. “The volatile oil in the gum is eliminated through the lungs, making this an excellent treatment for asthma.”

According to the NLM, it’s also used as a sedative, thins the blood and lowers blood pressure.

What’s more, rumor has it that asafetida is, or at least used to be, the secret ingredient in Worcestershire sauce. Heinz, which owns Lea & Perrins, doesn’t confirm this, but they don’t exactly deny it either.

Just before the ferula plants flower, in March and April, producers lay bare the upper part of the roots and cut off the stem close to the ground. They make a dome-shaped structure of twigs and dirt to cover the exposed surface and let it simmer that way for a month or so. Then they slice it and let the juice bleed out of the cut surfaces. This juice is then condensed into asafetida and shipped primarily to India, where it’s a staple of Indian cuisine and called hing.

We have turned up our collective noses at asafetida for centuries and saddled it with all manner of unflattering nicknames, but the plant continues to make itself useful (and even tasty) in a number of ways. Best of all, none of those ways include an asafetida bag.