In frontier days, hunters would often check a deer’s stomach for a “madstone,” a rock-like mass that many believed could draw the poison out of wounds caused by the bite of a rabid dog, skunk or other creature. Even though hunters today rarely examine a deer so closely, tales of folk medicine add an interesting topic for sharing in the deer camp.

Where did these fables originate? Accounts show the madstone treatment was used well before 1885, and a story about a madstone’s use appeared in the Floyd County Hesperian on July 6, 1922. In most accounts, the stone was heated in warm milk before application to the wound, where it stuck fast. When the stone fell off the wound, it was again placed in warm milk to cleanse it before repeated applications. The stone was reputed to draw the poison out of the wound, and when the madstone no longer adhered, the patient was believed to be cured.

These treatments seem far-fetched, but before Pasteur discovered inoculation against rabies in 1885, the only treatment available for a rabid animal bite was cutting and scarifying the wound.

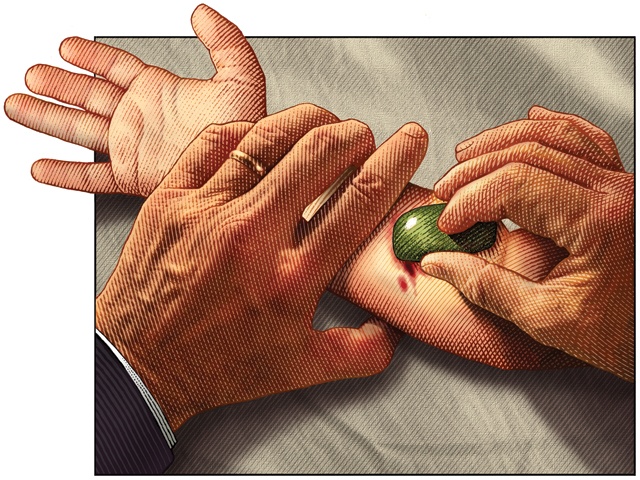

Descriptions of madstones varied widely. A legendary stone in Menard was said to be the size of a guinea egg, while a stone in Yoakum weighed nearly a pound and resembled a beef heart in shape. Descendants of “the Old Indian Doctor,” Benjamin Thomas Crumley, who practiced herbal medicine in Williamson and Lampasas counties, recall his madstone as oval-shaped and quartz-like, about 1 ½ inches in diameter and ¾ of an inch thick.

Dr. J.M. Noell and his descendants in the Alto area used a crystal-clear stone with a maze of small fissures. This stone, used on bites for more than 80 years, was said to have come from India. A trusted madstone in Van Horn was reportedly found on the bottom of a sailing vessel. Lavaca County’s wealthiest planter, Washington Green Lee Foley, claimed to have come upon a deer burying a madstone. He took the stone and eventually applied it to hundreds of bites.

Many stories tell of bite victims “riding for their lives” to reach a madstone. In 1879, the Galveston Daily News carried a report of a man from the Panhandle who rode for 96 hours to reach a madstone in Gainesville.

That same year, the Boston Journal of Chemistry reported that “a druggist in Texas lately paid $250 for a madstone.” Treasured as heirlooms and passed be-tween generations, many a stone came west with pioneers. Ben Milam, a central figure in the Texas revolution prior to the battle of the Alamo, gave a third of his family madstone to Collin McKinney, a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence and namesake of Collin County and its county seat, McKinney.

Like Noell in Cherokee County, many early physicians either utilized madstones themselves or recommended them to patients. Dr. W.J.W. Kerr, who settled in Corsicana after serving as a surgeon at Andersonville Prison during the Civil War, became widely known for the madstone in his medicine chest.

In 1921, years after madstones began to lose their popularity, Dr. Martha A. Wood of Houston wrote in the Texas State Journal of Medicine: “Madstones or enteroliths from the alimentary tract of the lower animals, are chiefly tricalcium phosphate, and possess none of the powers attributed to them.”

The following year, however, the story in the Floyd County Hesperian recounted the use of a local madstone to draw poison from the bite of a young Center boy. Floyd County Historical Museum board member Nancy Marble ran across the report and tracked down family members of the stone’s owner. She obtained the madstone for display in the museum and it can be seen there still, along with copies of the newspaper account.

——————–

Gene Fowler is an Austin writer who specializes in history.