My grandmother Florence Chiles was born in 1878 in Lockhart. She married John Terry Maltsberger in 1900, and they ranched the South Texas brush country in La Salle County. In the 1920s, they built a house in Cotulla and continued to operate ranches.

Florence was stylish, usually wearing hats and gloves when in public. She was Cotulla’s postmaster and was respected and persuasive. She had a strong sense of right and wrong and an instinct for power. She appointed herself advocate of the local Mexican American children, and by the mid-1920s, she was actively lobbying county leaders to build a school for them.

She cared deeply for the poor in her South Texas community, who lived in very difficult conditions. There was little education or health care and no social services. Most of them labored in the fields, working cotton, beets or spinach crops. And most of them did not see a way out of poverty.

She was able to grab county leaders by the nose and persuade them to support her plan for a school. After working all of her connections, she finally focused her efforts on the county judge, G.A. Welhausen. When she played her last card—proposing to name a new school after Welhausen—the county commissioners knew she had won. School bonds were approved in 1926, and the school was built by 1927.

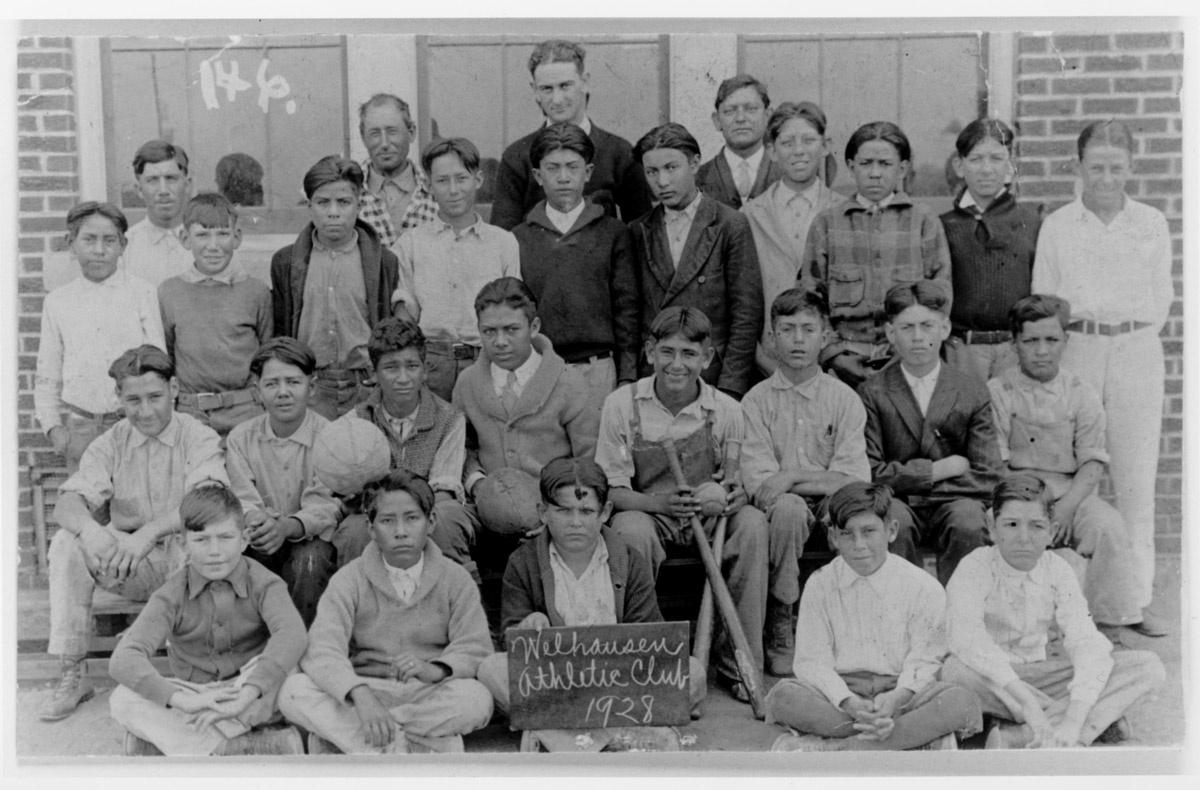

In 1928, 20-year-old Lyndon B. Johnson took a break from his studies at San Marcos Teachers College, now Texas State University, and accepted a teaching job at Welhausen School to help cover his tuition expenses. He was one of five teachers and taught mathematics and history to 29 fifth, sixth and seventh graders. He was shocked at the poverty he saw and how little many of the people had.

Johnson soon made friends with my grandmother, who was known as“La Florita,” and the two of them worked on improving conditions at the school. There was no playground equipment, cafeteria or school buses.

My grandmother urged Johnson to help lead the school, and he was soon promoted to principal. They encouraged Welhausen’s primarily Spanish-speaking pupils to learn English and get an education, knowing that it would open doors for them. Johnson created opportunities for his students and organized debates, spelling bees and physical education activities.

Johnson soon learned that Florence was his best champion for improving school conditions. She would march into county commissioners and city council meetings and de-mand funds for books and equipment. They rolled their eyes when she showed up, but she usually prevailed.

She persuaded city and county leaders to dedicate a city block across the street from the school as a park. Volunteers came together and built walkways, benches and a bandstand. The park was named Florita Plaza in my grandmother’s honor.

The school and park became the hub of the Mexican American community. There was a dance and celebration almost every Saturday night. Florence arranged for a surplus government building to be moved to the park, and it served as a community center where she presided over many fundraising efforts, including a massive annual rummage sale.

Working together, Johnson and Florence became lifelong friends, though Johnson returned to college after a year in Cotulla. The two of them corresponded for years. Florence’s only granddaughter, Terry Gay Puckett, attended a junior college in Washington, D.C., when Johnson was then a senator, and he showed her all the sights and even took her to Dwight Eisenhower’s inauguration.

Florence spent the rest of her life advocating for the Hispanic community, often driving sick or injured people to Santa Rosa Hospital in San Antonio. She worked on immunization campaigns and food drives and twisted arms for donations. She was a great woman.

Florence died in June 1963, when Johnson was vice president. He sent a huge floral arrangement for her funeral. Five months later, in the most tragic way, he became president of the United States.

Johnson traveled to San Marcos in 1965 to sign the Higher Education Act, which increased federal funding for universities, creating scholarships and giving low-interest loans to students. In a speech that November day, he said, “I shall never forget the faces of the boys and the girls in that little Welhausen Mexican school, and I remember even yet the pain of realizing and knowing then that college was closed to practically every one of those children because they were too poor. And I think it was then that I made up my mind that this nation could never rest while the door to knowledge remained closed to any American. So here, today, back on the campus of my youth, that door is swinging open far wider than it ever did before.”

Lee Gaddis is chairman of T3, a marketing firm founded by his wife, Gay.