Wrangler was my companion before I met my wife. Not having been in South Texas long, I didn’t know many people; all of my family lived in North Texas, and I wasn’t very social anyway. So when I wasn’t teaching agriculture and science at Lytle Middle School in Lytle, southwest of San Antonio, I was spending time with Wrangler.

I bought the little gelding when he was 3. Day after day, Wrangler and I traveled the rights-of-way along irrigation canals. Medina County had black, flood-irrigated farmland. Small canals that ran across the back of each field were fed from the main canal that went for miles to Medina Lake, north of Castroville. When a farmer needed to irrigate, he or she ordered water from the local water district. The water was directed to the farmer’s canal by other canals, and the water flow was controlled by a series of dams. When the water arrived, the farmer opened the stops on his canal, and the property was flooded.

The canal rights-of-way made an open path to roam and explore. We went through miles of corn, grain sorghum and warm-season vegetables in the summer. During the winter there were cabbage, carrots and wheat. Along the canals there was always something new to see. Wrangler had a long, smooth running walk; we could cover a lot of ground.

When I was at work, Wrangler was turned out with the Barbados sheep. Sometimes he pinned his ears and tried to herd them; sometimes the lambs followed Wrangler when they couldn’t find their mother. Mr. Salinas, my landlord, didn’t mind the horse being with his sheep—he made a fine guard dog.

But being the young horse that he was, Wrangler had a mischievous side. When we left his pasture to start out on a ride, I’d drop the reins when I opened the gate. He would follow me with his nose right at my shoulder. Where I turned, he turned. Once through, Wrangler would stand facing me until I latched the gate, took the reins and swung onto his back; I thought I was a regular horse whisperer.

One day we went through our normal gate routine. Wrangler stood facing me with a sleepy and innocent look as I turned to latch the gate. But this time, as soon as I took my eyes off of him, he bolted out of the yard and down the road—saddle, reins and all. When he had a half mile or so between us, he stopped, turned and waited until I got to him, as if he were showing me that he could get away when he wanted to.

Another time, it had been a long day at work when I drove down the lane to home. Wrangler wasn’t in his normal place. I looked in the back pasture, and then in the barn, but no horse. The fences were up and the gates were closed; he must have been stolen, I thought.

A Medina County sheriff’s deputy asked me to describe my horse. “He’s a little sorrel gelding,” I said, “with a freeze brand of a rising sun on his left hip.”

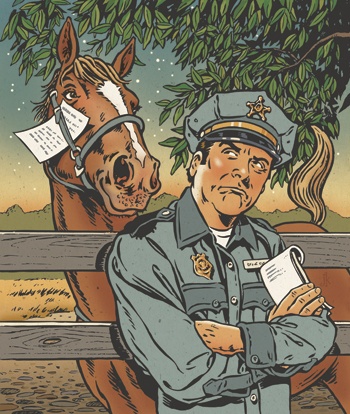

“Your horse is here in Hondo,” the deputy said. “You can pick him up at the stockyards along with his citation.”

With trailer in tow, I made the 30-mile trip to the stockyards where my horse was in custody. It seemed that he had jumped the fence, traveled a mile down the road and run my neighbor’s yearlings through the one-line electric fence that was holding them in. When a sheriff’s deputy found him, he was herding the calves down the highway toward LaCoste. The deputy wasn’t pleased with either of us. I accepted my scolding and headed for home with a ticket and a troublemaking horse.

I’m not the type to appeal a ticket, but this one said that my offense was “allowing livestock to roam on (the) highway.” There wasn’t any doubt that the horse was on the highway—I wasn’t contesting that, but he certainly wasn’t allowed to be there.

My court date arrived; I appeared in Hondo before the proper authorities and pled my case as they listened patiently. It was my luck that the district attorney had horses of his own. He said he knew that when “a horse had a mind to go somewhere, he would go.” Wrangler got off with 90 days probation, but the fee would be doubled if he were found roaming the highway again during that time. I assured the authorities that he would stay put.

The days of testing passed, and my little friend stayed out of trouble. After that, the only time he ran off was when I decided that he didn’t need a bridle and tried to ride him with just a halter and lead rope, or when someone else rode him and ignored my warning to keep him at a walk.

After a year or two, it was time for me to go back to college for more schooling. Knowing that I couldn’t afford to take care of Wrangler and pay tuition, I sold him to a junior barrel racer from Castroville. It was rumored that he became a good rodeo horse. I never saw him again, but I’ll always remember my little troublemaking gelding.

——————–

John Bird lives with his wife and three children in Eastland, where he works for the USDA Farm Service Agency.