In 1994, when Alida Lorio and her husband moved to the quirky Terlingua Ranch development north of Study Butte, where off-the-grid shacks sprout alongside hipster hideouts in the desert of far West Texas, they never expected they’d be living among black bears.

That changed in 2022, when several of the large, furry omnivores began ambling through their 110-acre, cactus-dotted backyard and diving for greasy pizza boxes in a dumpster.

“It’s like Terlingua Ranch just got invaded by bears,” Lorio says. “We have an arroyo right behind our house, and they were using that as a highway.”

Lorio reported the animals to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department officials who connected her with researchers at the Borderlands Research Institute at Sul Ross State University, up the road in Alpine. They set up traps and collared some of the animals as part of an ongoing, multiyear project to learn more about their movements.

Bears, they’ve discovered, are making a comeback in Texas. And as the animals expand their territory beyond just West Texas, it’s time for Texans to prepare to live alongside them.

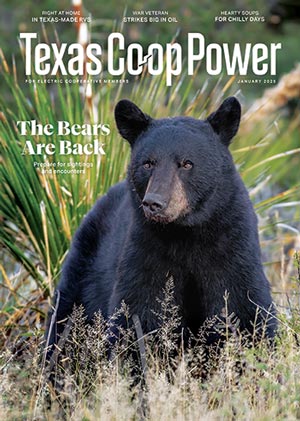

A black bear, seemingly unconcerned about a nearby photographer, feasts on prickly pear tunas just off the road in Big Bend National Park.

Jared Markgraf

Homeward Bound

Black bears once roamed across much of Texas, from the Big Bend to the Pineywoods, the Panhandle to the Rio Grande, but habitat loss and overhunting—along with ranchers who killed them over fears for their livestock—decimated their population. By the 1950s, they had been extirpated from the state.

A remnant population survived in the remote mountains of northern Mexico, though, and began to rebound. In the late 1980s, a few bears wandered across the Rio Grande and into Big Bend National Park. Now they’ve been spotted outside the park’s gates, along the Rio Grande and even as far as the Hill Country.

“A lot of that is due to the protected landscape, restrictions on hunting bears in Texas and most importantly, a change in people’s attitudes in the last 50 years,” says Matthew Hewitt, a wildlife research assistant who works on the Borderlands Research Institute’s black bear project.

The influx of the animals indicates improving habitat, but it also means an increased likelihood that humans will cross paths with bears, who are drawn to garbage, outdoor grills, deer feeders and pet food.

And that sometimes leads to conflict.

“Human-bear interactions are going to start becoming more common as bears continue to recolonize,” Hewitt says. “We’re working to get Texans in general to realize bears are a real thing and they do exist here.”

In 2020, someone shot and killed a bear that roamed into a Del Rio neighborhood. In 2022, a bear nicknamed Oscar began hanging around a dumpster outside a barbecue restaurant in Terlingua. The animals have popped up in Laredo, the Davis Mountains and Guadalupe Mountains National Park, too, and last September, TPWD officials trapped and relocated a bear on the outskirts of Uvalde, 85 miles west of San Antonio.

Three years ago, Melanie Kaihani noticed a bear on the 243 acres of land she’d just purchased near Sanderson, southeast of Fort Stockton. She set up a wildlife camera and struck gold: a bevy of bears cavorting beneath a deer feeder and climbing a salt lick to take a dip in the water tank she constructed for wildlife. You can watch their antics on Instagram.

“With their size and teeth and claws, you’d expect them to be really intimidating creatures, but they’re really just big, goofy raccoons,” says Kaihani. She notified researchers, who advised her to quit filling the deer feeder. “If they had opposable thumbs, they’d rule the world.”

For now, no one really knows how many black bears live in Texas, where they’re still considered threatened and hunting them is banned. “More than a dozen, less than a thousand,” Hewitt says. “Possibly a couple hundred.”

A mama and her three cubs meander along Chisos Basin Road on the way into the Chisos Mountains.

Courtesy Rick Roberts | National Park Service

Matthew Hewitt of the Borderlands Research Institute collects vitals on a bear that has been anesthetized.

Courtesy Austin Bohannon

Researchers want to know more about the bears—which have ears shaped like castanets; oval paws with candy corn-sized claws; eyes the size of a quarter; and a distinctive, musky odor—so they’re fitting them with collars to track their movements.

Their diet includes mostly plants: prickly pear tunas, acorns, wild persimmons, berries and seeds from piñon pine cones. They also eat insects and roadkill, and researchers in Texas have documented one incident of true predation (a javelina). Full-grown males typically weigh up to 300 pounds.

Bears Will Be Bears

Twice a year, in the spring and fall, Hewitt and others from the Borderlands Research Institute load baked goods and fruit into live traps they set on land where bears have been reported.

“We have learned that bears sure do like doughnuts,” Hewitt says.

When the trapdoor shuts behind a bear, the researchers get a text alert on their phones. Someone is always within a 90-minute drive.

“If a trap goes off, it’s boots on ground,” Hewitt says. “We jump out of bed, drop what we’re doing and drive out to the trap site.”

The researchers use a dart gun or jab stick to anesthetize the bear. Once it’s unconscious, they check its vitals; gather biometric data; attach tracking tags; and take hair, blood and tissue samples. Finally, they attach a rubber collar equipped with a transmitter and battery pack so they can follow the animal’s movements.

So far, they’ve collared about 30 bears, including five on Kaihani’s land near Sanderson and a couple on Lorio’s property in Terlingua Ranch.

“We have been extremely surprised by the sheer size of the area these animals are using,” Hewitt says. “We’ve seen some 80-mile movements from Terlingua Ranch down into Mexico.”

Another surprise? The bears are apparently thriving in the harsh, prickly environment of West Texas.

That’s why Borderlands researchers and scientists with TPWD want to educate the public on how they can safely coexist with the animals.

“Bears get into problems when there’s food involved,” Hewitt says. “Outside that, they’re good at keeping to themselves.”

By removing food that attracts bears, storing grills where bears can’t access them and installing bear-safe dumpsters, people can lessen the odds of a problem, Hewitt says.

If you do encounter a black bear, remember that it’s likely to scamper off if threatened or scared. Stay at least 100 yards away, and if you accidentally find yourself in close proximity to one, continue facing it and back away slowly. Bear spray is a good tool if a bear acts aggressively.

Also, consider yourself lucky.

A bear’s mighty paw.

Courtesy Austin Bohannon

“Take a second to marvel at a cool critter in a cool place,” Hewitt says.

Oh, Bother

Back at Terlingua Ranch, Lorio and her husband say they’re learning to coexist with their new neighbors.

“William and I are adaptive, and we figure the bears were here first,” she says. “So we just made some adjustments on how we dealt with garbage.”

They now store trash indoors. They rinse out pet food and other food containers to eliminate odor, and they put chicken bones in the freezer until trash pickup day. Bear-proof dumpsters have been installed in the rural neighborhood too.

Although not all her neighbors appreciate the bears as much as the Lorios do, Alida says she enjoys observing them.

“A lion is kind of regal, but bears look like you’d want to go have a beer with them,” she says. “The rare times that you do see them, it’s like a gift from Mother Nature.”