Drive across Texas and you expect to see cattle, oil pump jacks, and cotton or corn.

But grapes?

They’re more Texan and more common than you might think—increasingly so. And they’ve been here far longer than those pump jacks.

In fact, more than 14,000 acres of grapevines provide for some 600 winemaking facilities in Texas, according to the Texas Wine and Grape Growers Association. That’s way up from 3,000 acres and 200 wineries just a decade ago, a reflection of the rapidly expanding $24 billion Texas wine industry.

Claire Richardson is a winemaker at Burnet-based Uplift Vineyard near Lake Buchanan.

Erich Schlegel

Drew Tallent with a handful of iron-rich Hickory Sands soil at Tallent Vineyards, north of Mason.

Erich Schlegel

Spanish missionaries brought grapevines with them to Texas in the 17th century, and attempts at winemaking with wild mustang and muscadine grapes occurred until Prohibition.

Modern winemaking picked up in the 1960s as researchers at Texas Tech University planted grapes in the High Plains of the southern Panhandle, and producers are still refining what grows best where.

The state has eight American Viticultural Areas, distinct appellations of origin used on wine labels. AVAs define grape-growing regions and identify specific geographic or climatic features that affect the characteristics of grapes.

The Texas High Plains AVA is the most productive in the state, with more than 8,000 acres of vineyards, followed by the Texas Hill Country AVA with about 2,500 acres. The oldest, the Mesilla Valley AVA, established in 1985, straddles Texas and New Mexico in the El Paso area.

From left, Bob Young, Bending Branch Winery CEO; Tallent; and Jen Cernosek, Bending Branch general manager, at Tallent Vineyards.

Erich Schlegel

Ron Yates of Spicewood Vineyards. He sources grapes from the proposed Dell Valley American Viticultural Area in the Chihuahuan Desert of far West Texas.

Erich Schlegel

As the Texas wine scene continues to expand, more oenophiles are learning about what they taste in the state’s specific terroirs, nailing down hyperlocal characteristics that help them understand exactly what types of wines they like from each region.

“The entire country of France has more than 360 different appellations,” says Valerie Elkins, managing director of membership operations for William Chris Wine Co., based in Hye, between Fredericksburg and Johnson City. “Yet Texas is larger than France, and we only have eight defined AVAs. These AVAs help the consumer to identify regions and regional expectations, so establishing more AVAs helps get more national and international understanding.

“If you were to go to a restaurant today and order a chardonnay, you’d look for a California Russian River Valley chardonnay because that’s one of the regions where those grapes grow the best. We don’t really have that in Texas yet.”

Grape and wine producers await the approval of three viticultural areas by the U.S. Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. The process for establishing an AVA is tedious and slow. If approved, these new appellations would be Texas’ first since 2005.

Antony Moreno and his fellow grape pickers start at dusk and work overnight at Uplift Vineyard.

Erich Schlegel

Llano Uplift AVA

Located entirely within the Texas Hill Country AVA, the Llano Uplift AVA would cover 1.3 million acres. The greater Hill Country region sits over an ancient limestone seabed, meaning the soils are more alkaline compared with the slightly acidic soils of the uplift, which is marked by a geological formation made primarily of granite rather than limestone.

According to Justin Scheiner, associate professor and viticulture specialist at Texas A&M University and the petitioner behind this AVA proposal, the Llano Uplift has its own aquifer system, which impacts nutrient availability and water quality and allows for different rootstocks to be planted. The uplift gets less rain than surrounding areas, which contributes to the distinct character of wines made from the vineyards here.

“Aromatically, the wines in the Llano Uplift AVA exhibit more floral, delicate and perfumed characteristics,” says Claire Richardson, winemaker at Burnet-based Uplift Vineyard, which is within the proposed Llano Uplift AVA and a member of Pedernales Electric Cooperative.

“The wines are typically medium in body and have a distinct tannin structure that could be described as dusty or powdery,” she says, noting that depending on the vintage and variety, herbal characteristics can be present in the wines, including mint, eucalyptus and subtle green pepper.

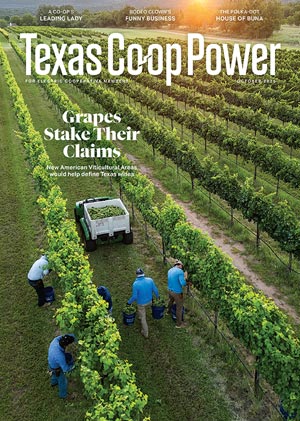

Uplift Vineyard is within the proposed Llano Uplift AVA.

Erich Schlegel

Tallent Vineyards in mid-July.

Erich Schlegel

Hickory Sands District AVA

This proposed viticultural area is located entirely within the western part of the proposed Llano Uplift AVA and on the edge of the Edwards Plateau in Mason County. Soils here are rich in iron, with granite and sandstone. Water from the Hickory Aquifer is important for irrigation.

Bending Branch Winery, based in Comfort and a member of Bandera Electric Cooperative, sources Hickory Sands grapes from Drew Tallent of Tallent Vineyards, one of the catalysts behind the application for this AVA proposal.

“Vines are able to root deeply into the soils of the Hickory Sands,” says Jennifer Cernosek, general manager of Bending Branch. “The Hickory Sands aquifer gives great water content to the soil, and the well-drained soil contributes to the fruit-forward nature of the wines from these grapes.”

Cernosek says that the wines Bending Branch makes from Tallent’s grapes tend to be softer in tannins, have a deeper mineral profile and are earthier.

“There’s a vanilla note in the wines that comes through across various grape varieties,” she says.

Harvesting at Uplift begins as the sun sets.

Erich Schlegel

Dell Valley AVA

In the Chihuahuan Desert of far West Texas, the proposed Dell Valley AVA is in Hudspeth County, west of the Guadalupe Mountains and east of El Paso.

The higher elevation here, 3,640–4,200 feet, provides diurnal shifts, which means it’s hot during the day and cold in the mornings, so that grapes can produce sugars in the heat and acids as they cool.

Ron Yates of Spicewood Vineyards, a member of Pedernales EC, sources grapes from Dell Valley. He says the distinctive altitude, soil and farming techniques come through in the grapes.

“For me, it’s probably the best-value fruit we have in the state,” he says. “Not a lot of folks are getting it, and it makes great wine. That mountain air up there is almost no humidity, so disease pressure for the grapes is less. Plus, deer aren’t roaming and eating your grapes.

“It’s probably one of the only places in the state that I have found where we can make lower-alcohol wine, and it’s still really jumping out with flavors and fruit.”

About Time

Establishing a new AVA involves filing a petition that takes time to be “perfected” to meet TTB regulation requirements, a period for public comment and then rulemaking finalization. It can take years.

But the Llano Uplift AVA, filed with the government in 2022, is close to becoming official; it’s third in line to enter a public comment period, followed by Hickory Sands, filed in 2023, which is 10th in line.

However, while the AVAs aren’t yet official, you can still enjoy wines from each of these areas at wineries and vineyards across Texas and beyond.

“Texas is becoming known as a world-class wine region,” says Elkins of William Chris Wine. “Breaking down our grow regions to show the unique characteristics of the soil and growing conditions will help raise awareness for the variety of terroir Texas has and continue to make Texas-grown wine more prominent in the national and international wine world.”