I was a lucky kid growing up in Panola County in deep East Texas. That was near Caddo Lake and Big Cypress Bayou, which feeds it. The headwaters of the Sabine River weren’t far away, nor was the fabled Big Thicket, home of Ben Lilly, the legendary bear hunter who guided Teddy Roosevelt in the early 20th century.

We all read “The Ben Lilly Legend” by J. Frank Dobie. It was in our school library, along with “Hunter,” by African guide J.A. Hunter. I read those books over and over. They instilled in me a desire to stalk wild game on the African plains, not to mention chase deer and wild hogs and gray squirrels in the big woods along the Sabine.

My luck continued through my father’s work as a Baptist minister. His status opened lots of doors and gates for my brothers and me. Hunting clubs made room for us during dog hunts for whitetails, and I always had a place I could go to hunt squirrels. Not to brag, but I got good at squirrel hunting, too, killing my limit of 10 per day more often than the men who showed up to hunt still a little queasy from a night’s whiskey tipping around the campfire. I still can’t understand why a limit of squirrels isn’t more to be desired than a belly full of booze.

But those nights spent in ramshackle cabins heated by a woodstove, with the chain-saw snores of old men rattling the windows, created a desire in me to recreate those same campfires and that same woodstove.

That’s why I still need to have a lease somewhere in the Hill Country, a place to spend the night in a camper, with my grandkids wrapped in their sleeping bags, dreaming their own dreams of big racks and rattlesnakes and wild hogs and rabbits begging for a .22 short or a .410 to rearrange their gray fur and send them to a frying pan full of bacon grease and then on to smother in a pot of gravy to get tender before they’re ladled onto a couple of cathead biscuits split open on a plate.

But good leases can be hard to come by. Most have been overhunted or ransacked by wild hogs or cut up by oil field roads and drilling rigs. All these things leave true hunters shaking their heads at what the search for water and oil and the unchecked shooting by folks without a feel for animals and land can do.

I’ve looked and looked close to our home in Burnet County for the right place to be able to take my grandchildren, who now number seven. I finally found a nice spot out near Buchanan Dam, just 12 miles from my front door.

There were lots of hogs, plenty of deer (though they were depleted by years of day hunting on a neighboring ranch), Rio Grande wild turkeys, and a 7-acre lake with lots of bass and ducks throughout the season. There was a community camping area; all we had to do was petition Pedernales Electric Cooperative for service for our trailers, and we were in business.

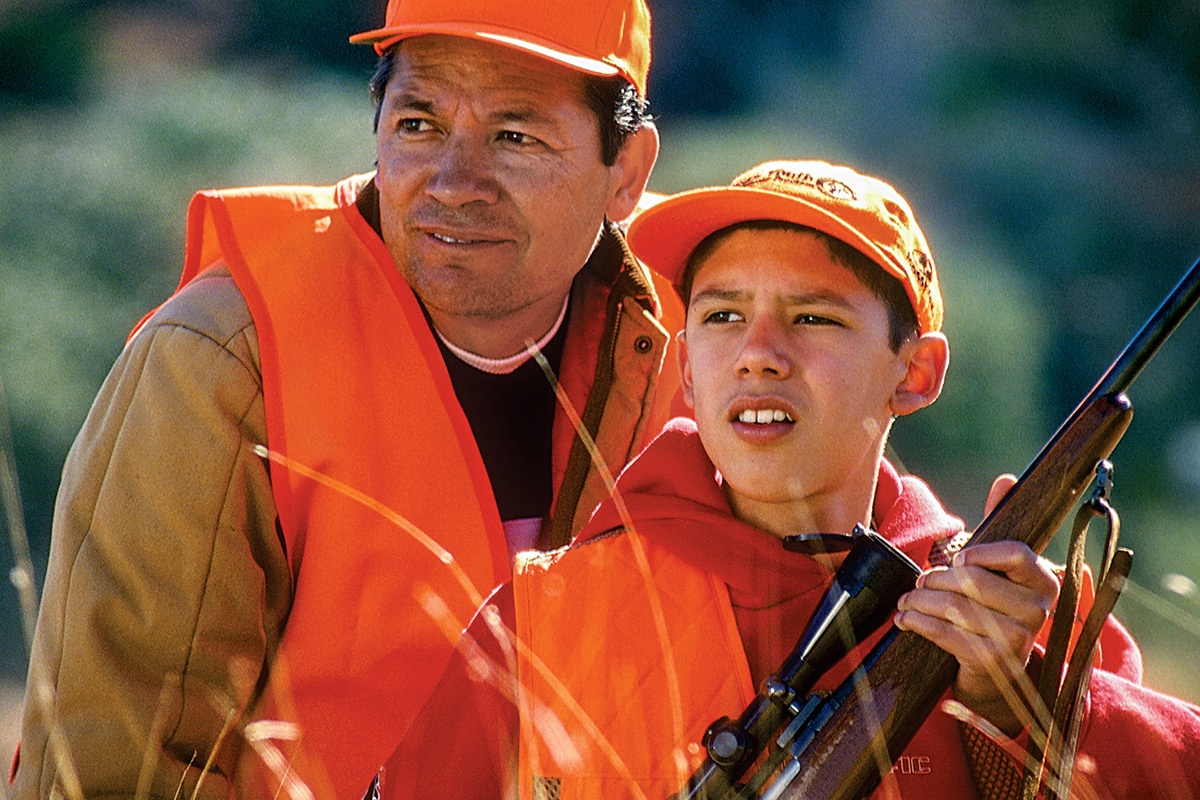

Our first night at the camp, I arranged several granite boulders to create a fire pit and gathered mesquite and oak logs for the fire. My daughter’s 8-year-old twins, Ben and Connie, thought it was perfect and right, and loved spending time there with me on the weekends. We could hike and fish and talk and watch the stars and animals. Life could not have been more right than it was when they were there. And isn’t that what a deer lease or a hunting camp should be? Kids and dogs and a deer hanging from a tree off to one side, sweet wood smoke and an occasional chain saw cutting up firewood.

Now I’m getting a renewed appreciation for the impact of deer camp life on kids. I see in my own grandchildren the wonder and awe and fear of things that go bump in the night that kept me from sleeping when I was their age.

During a late afternoon adventure, the grandkids and I walk around the lease. I am bombarded with questions—from the always-asked “What was that sound?” to the absurd “Why does the captus [sic] stick you?” to the tender “Come on, Pop, I think you could climb that hill.” Translated, that means, “We want to climb those rocks and are afraid you might not make it, but we hope you will at least let us do it.”

I’ve used my grandson Ben as a retriever a few times on dove hunts, and he did pretty well for not having a shock collar around his neck. And Connie is absolutely fearless about picking up all the toads and frogs and grasshoppers that abound out in the woods. If I catch a snake, she’s the first to hold it and let it wrap around her arm.

We’ve been squirrel hunting since they were 4 years old, when Ben offered to hold Connie’s hand so she wouldn’t be afraid going into the dark woods. After I shot a squirrel, she was the first to pick it up and hold it by the tail. “See, Ben, this is how you do it,” she said, adding, “I want to take it back and clean it so I can see the stomach and lungs and heart.”

I’m slowly getting over the urge to run every time I hear one of them squeal when they’re outside playing while I’m in the camper relaxing. It’s usually Ben who yells first, and Connie will say, “He always does that.”

Back in the camper for the night, we put on “Ghostbusters” and then “Young Frankenstein.” Luckily, I have the same taste in movies as the kids and can fall asleep with them piled on my feet and legs like dogs on a cold country night.

It’s about as perfect as a night could be.

A Lifelong Ritual

For me, life around deer camp has a sameness that’s comforting: up well before dawn for a Little Debbie cherry pie and a Diet Coke with my friend, Killis LaGrone, then off into the darkness to our bow blinds, cellphones handy in case one of us needs help. We’ve been hunting together since the mid-1960s, when I was invited to join their family deer camp in the old Beckville Hunting Club in East Texas.

Back then, we stayed in a makeshift shack that was part cooking tent, part bedroom. It was constructed using four sweet gum trees as corner posts with long two-by-fours as framing for the walls, two of which were old storefront signs from Killis’ grandfather’s Deadwood General Store.

Supper would often be baloney sandwiches stacked with meat from the store’s meat counter, or, if we were lucky, chicken-fried backstrap sandwiches cooked over his dad’s battered Coleman stove, which spewed fumes and monstrous heat and always left us on the verge of having to bail out of the little shack to stand outside in the cold.

There was a constant hickory wood fire going outside, close to the dog pens, where Killis’ dad, Clenton Sr., would store the cherished beagle hounds he used to move deer around in the woods. The sweet, peppery smell of hickory wood smoke today sends me sailing decades into the past.

Clenton would throw out his standard old saws about hunting, none of which had to do with camouflage or scent control but mostly had to do with, “Well, you go back down that old road to the leaning tree, then walk out across that flat to the right. There’s a big pin oak out there, and if you sit down under that tree, a deer is going to come by.”

Usually he was right—if we could find the tree in the dark of a cold morning. Today Killis and I will sit around the breakfast table and share stories while we plan our morning bow hunts. “Granddaddy never thought you should do that,” he will say of a plan we might be considering.

To this day, I’d rather have that warning ringing in my ears than anything else I can imagine when I start a day in the woods. I’m also spoiled by the attention Clenton paid to those of us he considered knotheads in need of help.

There are times I’ll be sitting in a blind with a fine deer in front of me, and I’ll make a decision not to take that particular deer because I don’t have anyone to share the moment with when it’s over.

I try to keep my own kids and grandkids interested and excited the same way, and it can bring tears to my eyes to have one of them say to me, “That was really great. Thanks for taking us, Pop.”

———————-

Mike Leggett is a writer and photojournalist based in Burnet.