Great-grandfather Lamont’s secretary was not a buxom blonde with shapely legs and a steno pad. It was an immense piece of antique furniture that stood in a place of honor against the wall of our living room all through my childhood. Far from appreciating it, my brothers and I avoided all contact with the towering wooden heirloom, a consequence of the many times that we were admonished “… NOT to throw the ball (block, shoe, tantrum, etc.) near your great-grandfather’s secretary!”

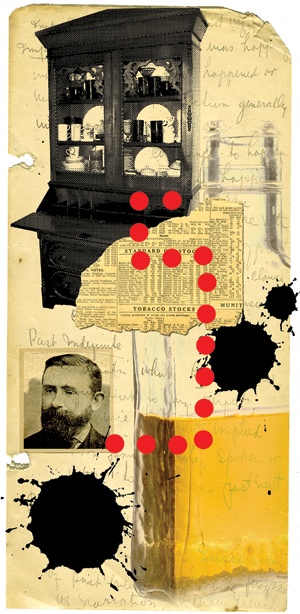

The “Field Guide to American Victorian Furniture” describes the piece as a “Gothic Secretary.” If by Gothic they mean looming and a bit scary in a darkened room, it is an apt description. The cove-molded cornice topped by a low triangular crown grazes the ceiling. Two glass doors close off a recessed bookcase above a foldout writing desk. Below are three recalcitrant drawers showing handmade dovetailed joints—if you can get the drawers open. They stick.

I have vague memories of my father’s tale that his grandfather, James Lamont, an Illinois legislator, wrote Prohibition papers on that very piece of furniture.

More than 50 years later, the stately secretary graced my own living room, and when I ran a dust cloth over its glowing walnut surface, I felt slightly ashamed. Its flawed glass doors showed the wavy reflection of an insensitive great-granddaughter. The secretary had a story to tell, and I had not thought to ask questions about it while my father was still alive to answer them.

Then I read a quote from author and psychologist Philip Carr-Gomm: “The songs of our ancestors are also the songs of our children.” Did I really want to ignore this link to my family’s history? Nagged by guilt and—I admit it—curiosity, I began to search for information about this relative’s lost story. One historical record at a time, the motivation for my search shifted from guilt to intrigue, then fascination.

Researching a 19th-century Illinois legislator from my home on the prairies of Central Texas proved a bit daunting for a genealogical neophyte like me. An aunt from Ohio, a dyed-in-the-wool family historian, dug up census records. (You must have excellent vision and a good imagination to read century-old census records.) Google helped with more basic information.

I discovered that Lamont was editor and publisher of The Monitor, a weekly Prohibitionist newspaper in Rockford, Illinois, but the major breakthrough came when my brother from Austin made a detour through Rockford on a trip to Springfield. There he found a research librarian in the Rockford Public Library who dug up a lengthy obituary and copied it for us.

Little by little, I learned details about Lamont that, like the layers of an oil portrait, helped him take shape in my imagination. Elected in 1886, he was the “original” Prohibitionist in the Illinois General Assembly and “had more than a state-wide reputation,” the Rockford Register wrote. And it said he was “a man of proverbial integrity, clean life and high ideals.” Now the faded man of my imagination held his head higher and wrote at his secretary with a purposeful flourish. Sadly, his high ideals once got him hanged in effigy by residents of Rockford who weren’t so enamored with his stand on the consumption of alcohol.

I’ve recently located a library at the University of Illinois that has some of his editorials on microfilm and is willing to loan them. I’m excited about the prospect of reading words penned by the old gentleman on the foldout desk that now holds a place of honor in my living room. I’ve learned that the piece was made before 1860, as indicated by the straight saw marks that show on the insides of the drawers. After 1860, circular saws were used. The inset metal lock plate has long since lost its key.

Behind the fold-down writing flap are five small compartments for filing paperwork and a tiny drawer with finger grips on the lower edge. Did these once hold the handwritten drafts of the editorials that so divided Illinois voters? “Mr. Lamont possessed great ability as a writer and speaker,” wrote the Rockford Morning Star in 1909, “and worked early and late for the suppression of the traffic in liquor … .”

I’ve never had the secretary appraised, but for me the connection to the editor of a small-town newspaper who dipped his pen and dripped ink on the desktop so many years ago and so many states away is far more valuable than its monetary worth.

A grainy old photograph of Lamont shows a serious man with dark hair and a Ulysses S. Grant beard, neatly trimmed and just beginning to gray. His tie fits snugly beneath a starched white collar, pretty much the way you would envision a straitlaced Prohibitionist. I wonder what he would think if he knew his old secretary was now an occupant of cowboy country. Would the beer cans in the ditch alongside the highway offend him?

Although Lamont died more than 100 years ago, he lives again for me because of an old piece of furniture. While I might not have agreed with his politics, I’ve begun to beseech my grandchildren NOT to throw the ball (cup, toy airplane, hissy fit) near their great-great-great-grandfather’s secretary!

——————–

Martha Deeringer is a frequent contributor who lives in McGregor.