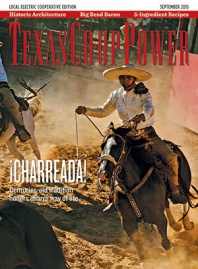

Almost every weekend in South Texas is an opportunity for time travel at the charreada. At San Antonio’s Charro Ranch, autumn has yet to break the spell of the heat and take the edge off the summer sun. Yet 24 men on horseback enter the keyhole-shaped arena, or lienzo, resplendent in brightly embroidered leather as they handle lassos and sweat profusely beneath wide-brimmed sombreros. The crowd leans forward, cellphones poised to snap digital photos of the 19th-century analog finery riding toward them.

Dating to 16th-century Spanish colonial Mexico, the charreada began as a celebration that marked the end of the ranching equivalent of a seasonal harvest: the cattle roundup. Teams of charros from sprawling haciendas throughout the region now known as Mexico and the American Southwest competed against one another in a series of events modeled on the equestrian skills needed for day-to-day ranch work. Throughout the turbulent period of American expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries, these competitions remained an important part of ranch life north and south of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Raul Gaona is a practicing physician by day, and a charro and historian on this topic in his spare time. He explains that the charro set the stage for today’s cowboys. He points out that many terms and traditions of American cowboys have roots in the charro tradition. Cowboys hold rodeos (the Spanish word for “roundup”), ride broncos (from the Spanish word for “rough” or “rude”) and dally rope around the saddle horn to keep a steer in control (from the Spanish dar la vuelta or “give it a turn”).

After the Mexican Revolution that started in 1910 dissolved many of the country’s large haciendas, charros formed teams of extended family groups to continue the tradition. Formalization of the sport came in 1933, the same year Mexican President Abelardo Rodríguez declared charrería the national sport of Mexico.

Through the 20th century, American cowboys modernized, adopting manufactured clothing, ropes made of synthetic materials and squeeze chutes. But the charreada traditions remain blazed in history.

Today’s charros adhere to strict regulations in attire to ensure historical accuracy in design and in materials. Charros spend thousands of dollars on the traje, or suit, as well as the saddle, hat and other accessories. Unlike in American-style rodeo, points in charreada also are awarded for style and personal carriage.

“Some of the things the charros do may look awkward or inefficient,” Gaona says, “but our interest is in preserving tradition.” For Gaona and the thousands of charros across the United States and Mexico, the events of the charreada, as well as the suit and the sombrero, provide a tangible link to the lives of their forebears.

It wasn’t a sport when my dad was doing it; it was a way of life,” says Juan Gonzalez, past president of the San Antonio Charro Association. The group, founded in 1947, is the oldest charro association north of the Rio Grande. More than 200 teams compete in the United States, with more than 30 across Texas in Austin, El Paso, Dallas, Houston, Del Rio and San Antonio.

At the Charro Ranch arena in San Antonio, the charreada begins with a parade to “La Marcha de Zacatecas.” Charros fan out in teams, circling in a grand display of pomp for the judges. The announcer calls out the names of ancestral homelands in Mexico, eliciting shouts from the crowd and a roar of mariachi horns.

Each event, or suerte, that follows the parade is an embodiment of centuries-old ranching tradition. Fans of American rodeo will recognize bronc and bull riding and some of the team roping events, but others, such as horse reining and “forefooting,” display skills in slowing down or redirecting livestock, all with an emphasis on style over speed.

Coleadero, or steer tailing, is one of the oldest traditions of the charreada. A mounted charro races after a running steer, grabs its tail and wraps it around his leg, tripping the animal as he passes by. A wayward animal instinctively wanders back to the herd after a fall, and thus a 19th-century charro could keep his herd together without ever having to dismount or use his lasso. For the modern charro, points are granted for technique, speed and the roll of the steer.

The escaramuza, or skirmish, comes next and honors the contributions of women during the Mexican Revolution. A team of eight women performs a high-speed, synchronized routine set to music. The women ride sidesaddle in full skirts and heavy dresses with crinolines underneath, referred to as “Adelita” attire. Escaramuza is one of the biggest crowd pleasers, with blurs of color that trace patterns and fan out across the arena.

For bull and bronc riding, points are given for technique but also for the difficulty of the ride. If a bull has a lot of kick, or the charro decides to ride backward, he stands a better chance at a higher score. Unlike American rodeo, the charros ride until the animal quits kicking, usually much longer than eight seconds.

In the manganas, or forefooting, teammates chase the mare while the charro displays his best floreos, or flourishes with the lasso, for the judges. In the Charro Ranch arena, a charro jumps in and out of wide, spinning circles of rope, adding as many as he can before trying to lasso the running horse by the front legs. Points are given for the speed of the roping and flourishes performed.

For a newcomer to the tradition of charreada, the subtle details and fine points of scoring as well as the pace of the events can be mystifying. Sidling up to an old charro in the crowd and asking a few questions is a fast way to an earful of history and insight into the events and the standings of teams. Gonzalez serves as guide for my initiation to charreada, and he points out the up-and-comers.

In the final charro event, paso de la muerte, or pass of death, a charro riding bareback leaps from his horse onto a wild mare and rides her to a stop using only her mane for support. If he falls, the charro risks being trampled by the mare or his mounted teammates who are following at full speed.

Just as in the old days of the hacienda, there are no cash awards, but the prize is the respect of fellow competitors. Following this tradition means that bragging rights and personal recognition are more important than the prize buckles and saddles common in the rodeo world, Gonzalez explains.

As the afternoon transitions into evening, audience members throw boots and hats from the stands into the dusty arena to acknowledge the excellent performance of a young charro. He returns the boots and hats one by one, engaging in a personal exchange with each of his admirers. Gaona and Gonzalez are hopeful that the next generation of charros will carry on the tradition, one suerte at a time.

——————–

Julia Robinson is an Austin photojournalist.