To understand what drives María Alma González Pérez, one must understand her love of language. Because her mother had only a grade school education, González Pérez mostly spoke Spanish—the only language she knew until enrolling in school—with clarity and precision.

“She did not want us mispronouncing words,” González Pérez says. “She would say that the proper use of the language was something that defined you as an educated person.”

Upon that principle, González Pérez earned a doctorate in education, then became a professor, college administrator, children’s book author and, most recently, an entrepreneur—all while advocating for the importance of language. González Pérez, 70, is now a decade into her latest career—a publisher on a quest to bring more Hispanic culture into children’s books.

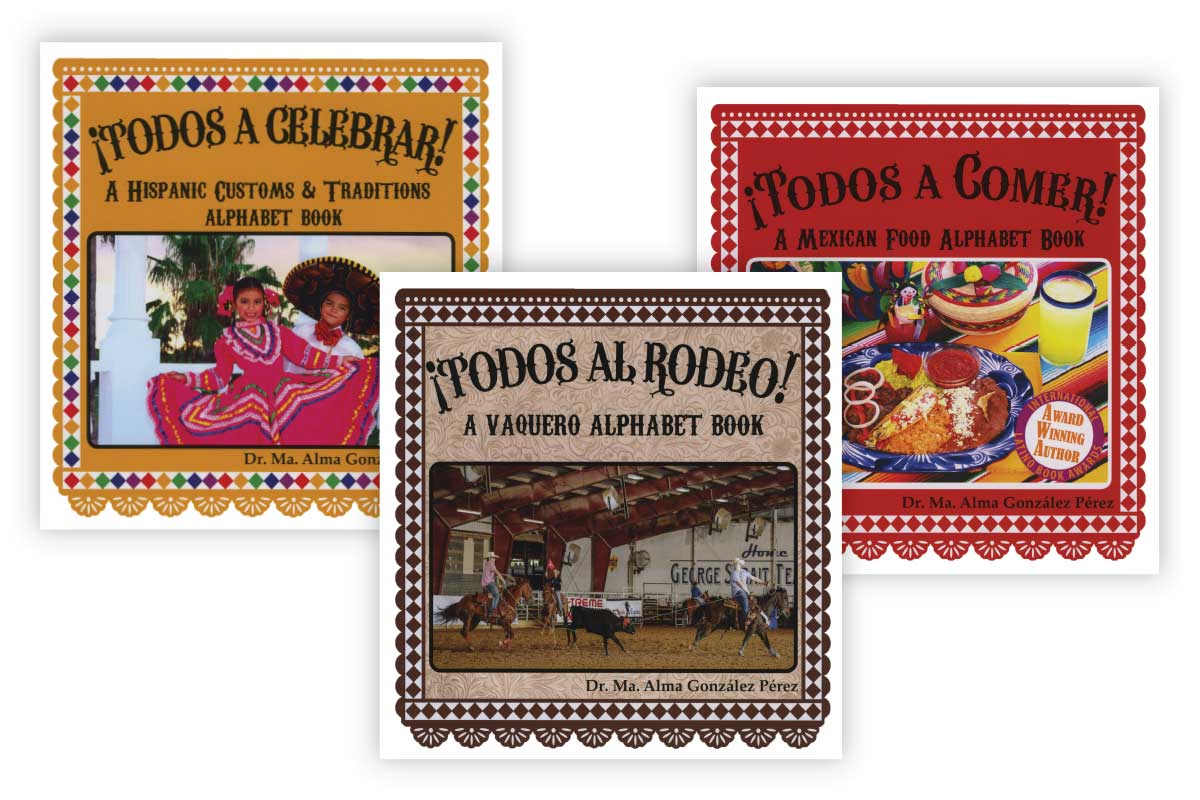

The native of Zapata County, on the border in South Texas, won a prestigious International Latino Book Award in 2021 for her book ¡Todos al rodeo! A Vaquero Alphabet Book. The children’s picture book is the third in her series of what she calls “ABC books,” which tell a story through the letters of the alphabet. She uses the genre to infuse Hispanic culture into children’s literature to foster bilingual literacy.

It’s the kind of book she wishes she had as a young student.

“I was always trying to unravel this mystery called English,” González Pérez says. “It was a sink-or-swim approach to learning.” Her moment of awakening, she says, came in the eighth grade, when she first enrolled in a Spanish course and received a textbook for that class. “This is the book they should have given me in the first grade,” she says. “They did it backwards.”

González Pérez’s vaquero book teaches children that the American cowboy and the cattle industry itself emerged from the arrival of Spaniards who introduced the horse to North America. Words like “rodeo” and “lasso,” the book points out, are Spanish in origin.

The book also draws from the author’s own life; González Pérez, a member of Medina Electric Cooperative, comes from a land-grant family whose large property holdings were bestowed on early Texas settlers by the Spanish crown. She grew up on a 1,000-acre ranch that touched the banks of the Rio Grande, so she’s familiar with the vaquero way of life. Her Texas roots reach back so many generations that she calls herself a Tejana instead of a Mexicana.

González Pérez frequently uses the Spanish word for courage—coraje—as she speaks. Her cultural awareness in a part of the state where Hispanic culture is the norm gave her the coraje to excel in school even though she had to learn English while she was learning other subjects. And her mother’s insistence on excelling gave González Pérez a sense of self, she says. “I never felt that I needed to be anybody else other than who I was.”

So with a sense of coraje, González Pérez left the cultural comfort of South Texas to master English by immersion. She attended Texas Woman’s University in Denton in the 1970s, then “relatively devoid” of Hispanic people, she says.

After securing undergraduate and master’s degrees, González Pérez returned to South Texas, where she taught, raised a family and eventually attended Texas A&M International University in Laredo for her doctorate. Her dissertation on the relationship between Spanish proficiency and academic achievement among high school graduates in South Texas fueled what would become a lifelong pursuit.

Literacy, her study showed her, extends beyond the pages of books into cultural understanding. It’s the context on which idioms are built and understood, and it’s the antitoxin of cultural misunderstanding and outright xenophobia.

Literature, she believes, immerses readers in the experiences of others—puts them in the shoes of protagonists. But as a professor at the University of Texas-Pan American (now UT Rio Grande Valley), González Pérez was frustrated by a lack of culturally relevant Hispanic literature available for her students. They were studying to become bilingual teachers using a curriculum based in English.

“I started gauging them, and that’s when I learned that they had not been exposed to any literature written by Hispanic authors,” González Pérez says. That sparked something in the professor.

Lino Garcia Jr., a retired UTRGV professor, sees the need for Hispanic stories from Hispanic authors.

“We should be doing that at the pre-K level,” he says. “Instead of talking about the Taj Mahal, we should be talking about Spanish missions, about the Camino Real—about things that Hispanic students can relate to. This gives them a sense of identity. This gives them a sense of worth.”

González Pérez’s ABC books.

González Pérez’s first book was ¡Todos a Comer! A Mexican Food Alphabet Book—the best-selling of her series for children. The second book, ¡Todos a Celebrar!, spotlighted Hispanic customs and traditions.

Of course, writing culturally inclusive books is one thing; getting them distributed, González Pérez discovered, was a big, new challenge. So with the help of her three daughters, she launched Del Alma Publications (del alma means “of the soul”). An attorney, a business major, and an engineer and graphic designer, Anita Pérez, Maricia Rodriguez and Teresa Estrada, respectively, helped their mother get the business going in 2008.

“I have a dream team in my daughters,” González Pérez says. “I told my daughters, ‘Let’s play with it for five years. If it flies, great. If it doesn’t, nothing was lost but a lot was learned.’ ”

It flew.

González Pérez’s initial goal was to target South Texas. But her first bulk order of more than 25 books came, instead, from Redondo Beach, California. Next came an order from Philadelphia for several hundred books. The demand was nationwide. Del Alma Publications has shipped thousands of books over the past 14 years—to individuals, schools, libraries, book donors and nationwide book distributors.

But she isn’t done yet.

“We’ve made great strides in meeting the biliteracy challenges of the Hispanic learner,” González Pérez says. “However, we still need to write many more books about stories that our children need to read.

“Not only to inform and educate but to help them develop a greater sense of cultural identity and pride.”