The Lone Star State is known around the world. The town of Lone Star, however, isn’t well known—even among Texans.

But it should be. So says a group of 13 volunteers working to bring light to the East Texas town of 1,400 people about an hour southwest of Texarkana. They want to share the rich history of its steel plant, metal from which spanned the skies over Vietnam and the subsurface of the oil industry and deeply impacted the U.S. economy, environment and space exploration.

They call themselves the Ladies of Lone Star, and their goal is plain.

“We want to gather memories and record as much of the history of Lone Star Steel as possible for future generations,” Lesley Dalme says.

It all began with an idea about décor.

Randy Hodges, former Lone Star mayor who was technical services manager when his 45-year career at the plant ended with its closing in 2020, proposed adorning the walls of the Lone Star Senior Citizens Center with pictures of the plant. The framed photos caught the attention of locals, and the project was born.

Workers with one of Lone Star Steel’s products.

Courtesy Ladies of Lone Star

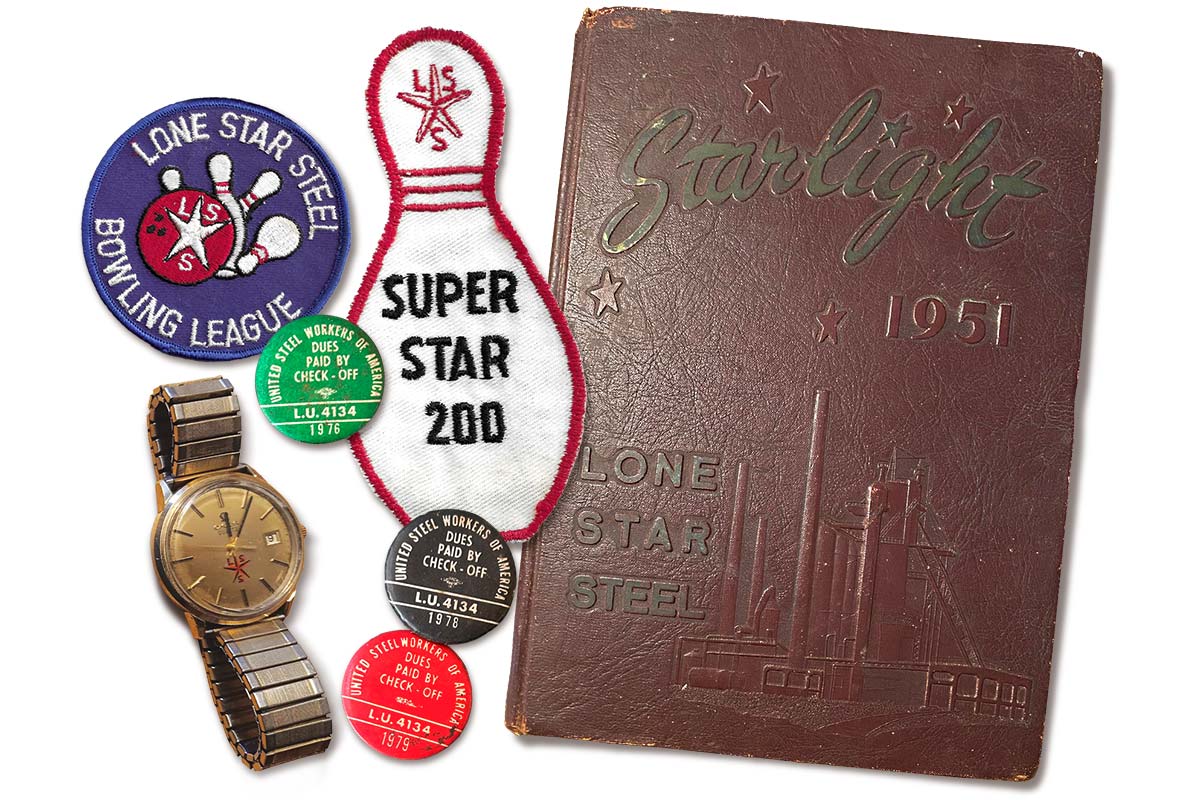

The Ladies of Lone Star are dedicated to preserving memorabilia from the mill and its employees, including a yearbook from 1951.

Courtesy Ladies of Lone Star

I sat down with three members of the Ladies of Lone Star as well as Hodges and John Shivers, a former plant manager and vice president. For nearly two hours in the chapel on the grounds of the shuttered plant, I listened and learned about the steel industry, the plant’s history and the impact it had on people, places and events far and wide.

The plant was built with federal funding during World War II in the small town of Lone Star, selected because of its strategic location. Nearby are ore, limestone and coal—the three essentials for steel production—and the Port of Houston is driving distance.

While the 600-acre plant came about because of the war, steel didn’t start rolling out until the mid-1940s, after the war’s end. In the early 1950s, the oil industry began booming and with it the market for pipe.

“An idea came about to buy surplus war project product to manufacture oil pipe,” Shivers says. “It took two years to adjust production and install necessary mills at a cost of $76 million. The oil industry fluctuated, going from boom to bust. Likewise, LSS profited hugely and suffered severely.”

LSS also played a role in the Vietnam War.

“We would make large-diameter tubes to be used as bomb casings, which would be cut to bomb length, shipped by rail or truck to an ammunition plant in Karnack, filled with ammo, a fin was attached, then they would be transported to the Port of Houston,” Shivers says.

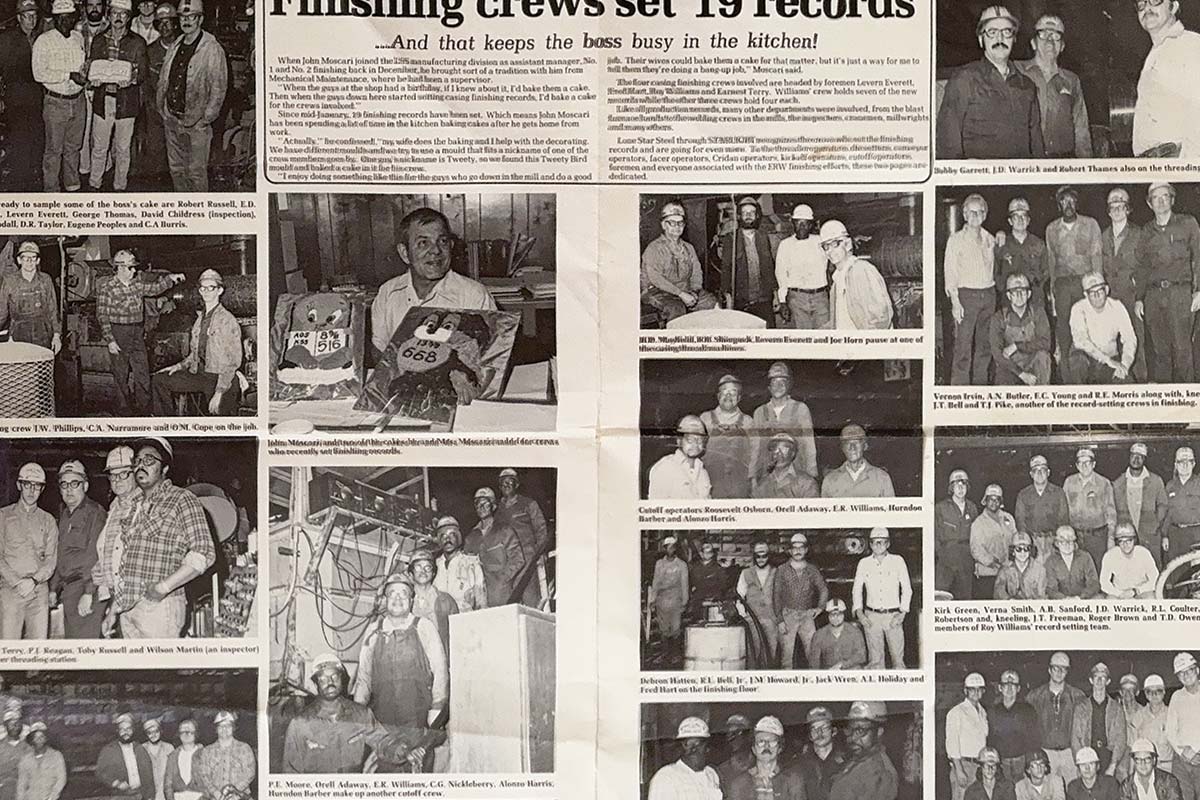

A spread from the March 1980 issue of the company’s newsletter.

Courtesy Ladies of Lone Star

Several volunteers from the Ladies of Lone Star in the mill’s chapel, the site of hundreds of plant employees’ weddings over the years.

Jay Patrick

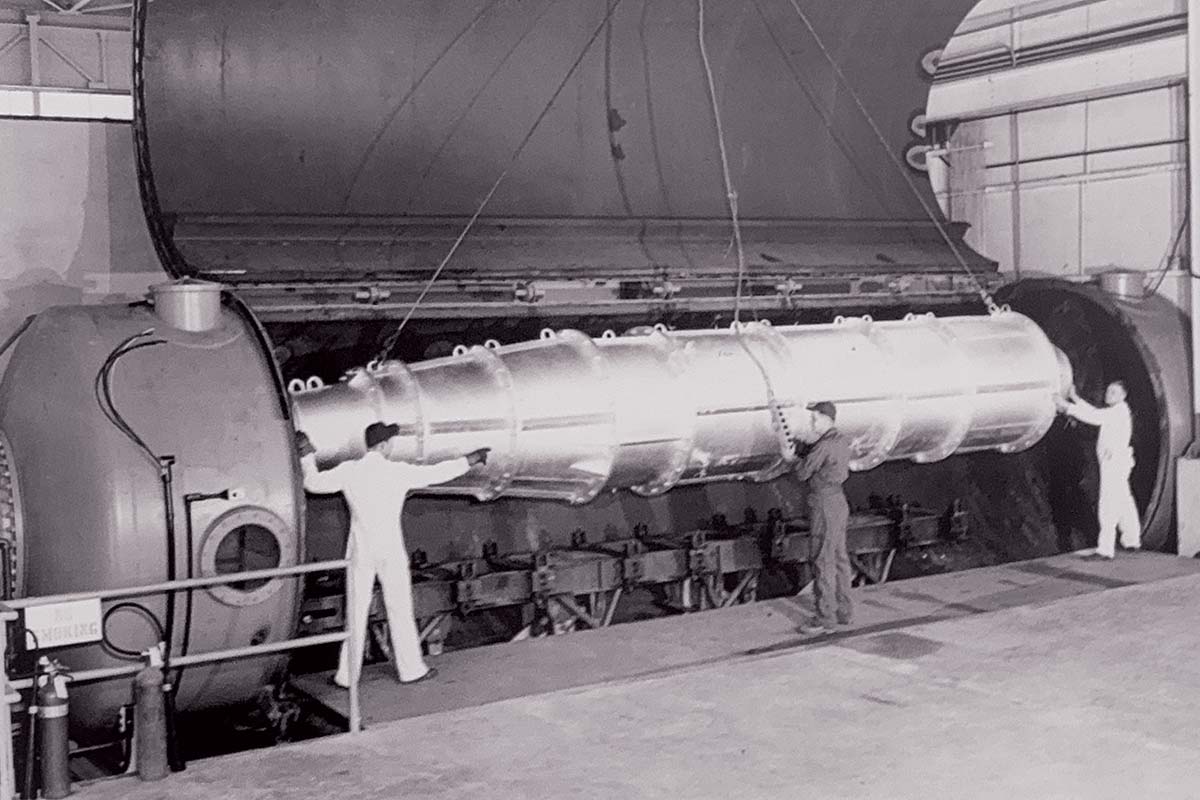

The steel mill had a wind tunnel that could simulate the vacuum of space using blast blowers. Known as the Ordnance Aerophysics Laboratory, the highly secure site operated from 1945 to 1968 and employed hundreds of scientists, technicians and engineers. Department of Defense contractors conducted thousands of tests for supersonic jet engines, guided missiles and spacecraft components for the military and NASA.

“The facility was well-known around the community, but because of security, it was not known around the country,” Hodges says. “They researched and designed rocket engines here, including components used for the Saturn rocket. They would bring equipment in on a bread truck, and once inside the plant, securely situated behind closed metal doors, the bread truck doors would open, and parts would be unloaded.”

Members of the project liked the area so much, amid the verdant Pineywoods and alongside the 1,500-acre reservoir built for the steel plant, many of them stayed and went to work for LSS.

They brought with them a wealth of knowledge and talent that led to industry innovations. For example, a device that scrubbed smokestack emissions was developed at LSS, Shivers says.

A wind tunnel that could simulate the vacuum of space using blast blowers.

Courtesy Ladies of Lone Star

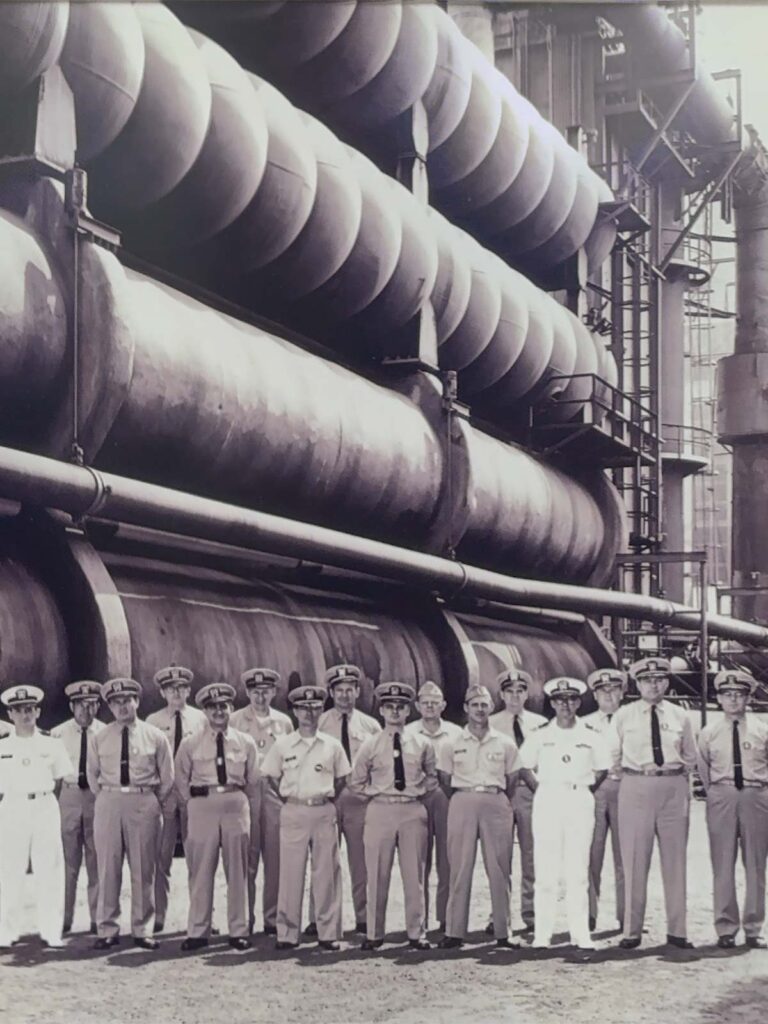

Servicemen assigned to the Ordnance Aerophysics Laboratory at Lone Star Steel some 70 years ago.

Courtesy Ladies of Lone Star

Randy Hodges, the former mayor of Lone Star who worked at the plant for 45 years, with his father’s hard hat.

Courtesy Lesley Dalme

“It cleaned better than anything on the market,” he says. “We sold it to other cities—Houston, Shreveport—a nuclear facility in Georgia, and other customers in the U.S. and abroad.”

However, economic downturns in the 1980s plagued the steel industry. In 1989, Lone Star Steel filed for bankruptcy.

“Our labor contract expired, and we worked two years without one,” Shivers says. “We just kept going, no contract and no complaints. It took a couple of years, but we came out of bankruptcy and paid off 85% of the debt, and a few years later were profitable again.”

In 2007, U.S. Steel purchased the plant for more than $2 billion. Nine years later the mill was idled and then completely shuttered in 2020. At the height of production, the company reportedly employed more than 6,000. Now, other than security personnel, the facility is vacant. Equipment sits silent while rust and dust mount.

The Ladies of Lone Star are dedicated to preserving documents dating to the early 1940s and photographs showcasing the plant’s long and vibrant history. They also have begun meeting with former employees, recording and then transcribing their stories to be compiled into a book chronicling the mill’s story.

“The plant is being dismantled, and eventually it will be no more,” says Lanita Goodrum, one of the volunteers. “And it’s even more important that people know what made Lone Star, what those men did in that plant and the impact it had on our nation.”

From left, former mill worker Bruce Shimpock and Lesley Dalme and Lanita Goodrum of Ladies of Lone Star look over artifacts.

Jay Patrick

When our time together winds down, Hodges, who started at the steel plant in 1974, offers a trip to the senior center—an invite I eagerly accept. As we walk by each photo on the walls, he enthusiastically explains the images.

“I worked with World War II vets, young men with families—our plant was filled with people like that, hardworking parents who had to make a living regardless of the long hours, the hard and dangerous work,” he says. “In a world that was so divided, we were working for a common cause.”

On top of a piano is something that goes beyond mere nostalgia—Hodges’ father’s hard hat from his long career at the plant. “His first paycheck in 1953 is what paid for my mother to go and me to be born at a hospital,” Hodges says. “It was more than a job and career. We were family.”

And it was a family that survived, thrived, accomplished a lot and had an enormous impact. They are proud of LSS, still—its impact of 80 years, from Earth to the heavens, the industries it changed from oil to aerospace, and the lives it touched.

As Shivers says, “Our footprint ranges far beyond this steel plant.”