David Getman was working in a music store in Brooklyn, New York, in 1997 when a friend gave him a box of banjo parts. The friend suggested that he see what he could make with the pieces.

Getman was intrigued. “I was 22. I had no tools. I wasn’t a woodworker,” he says. “But I liked to tinker.”

After fashioning a banjo from the parts, Getman became more interested in the instrument that has deep roots in North America. “I wasn’t a big fan of bluegrass, but I liked syncopated picking.”

Experimenting with playing and composing his own banjo music led Getman to develop a deep appreciation for the Appalachian style of banjo playing known as frailing or clawhammer. Unlike the three-finger bluegrass style, which typically consists of an up-picking motion by the fingers and down-picking of the thumb, clawhammer is all down-picking with a clawlike hand.

Clawhammer is typically done on an open-back banjo that produces a more mellow sound. Getman likes “the rich, deep notes, like rolling thunder” that these banjos produce. Seventeen years after that first banjo, Getman discovered rotted floor joists in his Houston home. He bought tools to do the repair work. Then he wondered what else he could do with his expensive new tools. That led to a new avocation.

Today, as a banjo-maker, restorer and player, Getman, 49, runs Lindale Banjos out of his home in Houston’s Lindale Park neighborhood while working full time as a social science researcher and raising a son and daughter with his wife. He’s proud that the renowned Fiddler’s Green Music Shop in Lockhart accepted one of his banjos in 2021—the first he made that he thought was good enough to sell. The store has been selling his instruments ever since.

“Fiddler’s Green is known to musicians beyond Texas. They have customers from as far away as Japan,” says Getman, who plans to make banjos full time when he retires.

A banjo handmade by David Getman.

Nathan Lindstrom

Detail of a custom-inlaid headstock on a Getman banjo.

Nathan Lindstrom

Getman sands a banjo rim in his Houston workshop.

Nathan Lindstrom

Banjos come in two distinct styles. Bluegrass musicians prefer banjos that have wooden, bowl-shaped attachments called resonators on their backs. A resonator projects the sound outward toward the audience. Getman makes clawhammer banjos with open backs, a style used by musicians who play old-time or Appalachian music.

Making a banjo of either style is a long, complicated process.

“A guitar is made entirely of wood, but a banjo has both metal and wooden parts,” says Jim Penson, another Texas banjo-maker. “Quality bonding of those two different materials requires quality workmanship.”

Penson, who also restores, plays and teaches the instrument, makes resonator banjos at his shop in Arlington. He works in intervals of 15–20 minutes that total 80–100 hours for each banjo he produces. Between work sessions, he must allow time for lacquer or glue to dry completely before undertaking the next step.

“The most difficult part is also the least important. It’s finishing the instrument, making it look glossy,” says Penson, 69. “People who spend a lot of money for a custom-made banjo want it to look perfect.”

The Penson family lived in a 120-year-old farmhouse in Illinois, and his father was always restoring something in the house. Watching and helping his dad got him interested in woodworking. He moved to Texas in his 20s and got much more involved with banjos. He played in various bluegrass bands, including one with the late Earl Scruggs, considered the most influential banjo player in the world.

About 25 years ago, he opened Penson String Works, where, amid demand for his custom guitars, he turns out three banjos every year.

“You can use good components and not make a good banjo,” Penson says. “You can have not so good components and good workmanship and get a good banjo. It’s kind of the luck of the draw.”

One of Getman’s personal favorites is a mahogany banjo he made in 2022.

Nathan Lindstrom

A detailed view of the headstock on Getman’s mahogany banjo.

Nathan Lindstrom

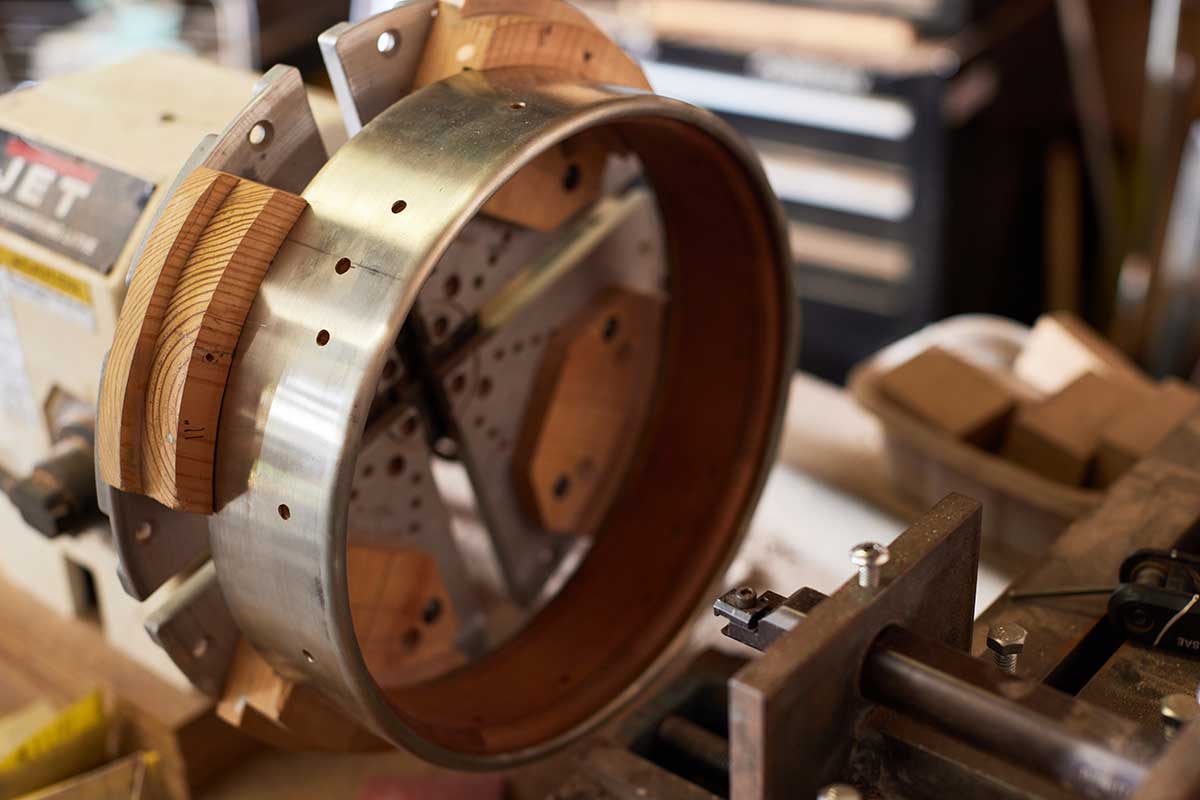

Long soaks are required to make the wood pliable enough to be formed into the banjo’s round rim. Getman gains back a bit of that time with efficiency: He cuts four of each part before resetting his lathe. Still, it takes several weeks to finish a banjo.

Getman likes to use walnut because it’s sustainable and easy to get, but he also uses cherry. Maple is a popular choice for banjos, but it’s lighter—almost bright, he says, in appearance and tone. He prefers “the darker woods, walnut and cherry, for both the aesthetics and the tones they give the banjos.”

The most challenging aspect of making a banjo is “the tedium of sanding,” Getman says. “You want the finished wood to look like glass. You sand parts five, six, seven times with different grades of sandpaper until it feels as smooth as it can be.”

An unfinished, glued-together laminated rim.

Nathan Lindstrom

Getman plays his mahogany banjo in his workshop in Houston’s Lindale Park neighborhood.

Nathan Lindstrom

And the most difficult part?

“From a technical point, it’s making the part at the end of the neck where it meets the pot,” Getman says. “Cutting that exactly right is next to impossible without the right tool.”

An experienced banjo player looks for an instrument that feels good in their hands, Getman says. The tone and volume should be consistent up and down the range of notes. Custom banjos can cost $1,200 or more, and musicians often request custom inlays of ivory, mother of pearl and other expensive materials for the headstock and fretboard.

One of Getman’s customers requested a headstock inlay depicting the night sky. Getman had saved a burl of wood—what looks like a knot when it’s attached to the tree trunk—because he liked its wavy grain. He added black ebony for the sky and cut the burl open to represent ocean waves below.

It’s challenging work but the rewards are plenty.

“Hearing the finished product is the best part,” says Getman, who makes four or five banjos a year. “You take the different pieces and your ideas, and then when it’s finished, you get to hear that banjo’s tone.”

Getman uses a dragon rasp to work the neck of a banjo.

Nathan Lindstrom

Forming a perfectly round rim is part of the time-consuming process of constructing a banjo.

Nathan Lindstrom

Getman made these custom jaws that hold a rim on a lathe for shaping and sanding.

Nathan Lindstrom