Before Kilgore had Gussie Nell Davis and her Rangerettes, the small East Texas town had Daisy Bradford No. 3, the famous oil well that opened up the legendary East Texas oil field in 1930.

The boom didn’t last long, however. The wider world might not have ever heard of Kilgore again except for the fact that Davis showed up in Kilgore about the same time that the oil boom played itself out. Kilgore College President B.E. Masters hired her to form an on-campus organization that would bring more women to the college while at the same time keeping the men in their seats at halftime of football games, instead of sneaking off to take a nip under the bleachers. By forming the first group of Kilgore Rangerettes (named to coincide with the football team’s Ranger mascot), Davis created the world’s first women’s dance-drill team and also managed to strike a lasting blow for Saturday sobriety in East Texas.

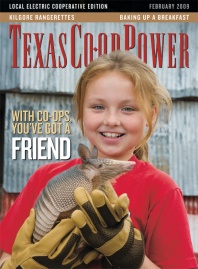

Since their debut at that first halftime show on September 12, 1940, the Kilgore Rangerettes have performed at halftime of dozens of college football bowl games and at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. They have toured Venezuela, Romania and France and performed in Hong Kong, Singapore and Dublin. They were at the presidential inaugurations of Dwight Eisenhower and George W. Bush and have graced dozens of magazine covers. The Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston spotlighted the Rangerettes as a “living art form” in 1977. Pro Football Hall of Fame member and sportscaster Red Grange dubbed them “sweethearts of the nation’s gridirons.”

Most recently, the Rangerettes are the subject of a book of photographs from the University of Texas Press titled simply Kilgore Rangerettes. The photographs are by O. Rufus Lovett, a fine arts photographer who has taught at Kilgore College for more than 30 years. He began photographing the ‘Rettes in 1989, eventually compiling this collection to capture the unique artistry of the group, along with the small-town life lived by the 65 or so mostly teenage girls who make up the team each year at the two-year community college.

What comes through in these photographs is that the Rangerettes have changed little, if at all, in the past 69 years. They still have the same costume: a blouse, arm gauntlets, belt and a short circular skirt done up in red, white and blue along with white, Western-style hats and white boots. They still perform their trademark “high kick” where they raise a leg high enough to touch the brim of their hats. Photographer Annie Leibovitz, who features the Rangerettes in her book Women, said later that after the team had performed the kick, the drill team captain told the Rangerettes to “wipe the lipstick off your legs.”

We can be sure that Gussie Nell Davis—”Miss Davis” to generations of Rangerettes and anybody else who knew her—probably gave the same instructions during her 39 years as the group’s director. She was a no-nonsense kind of woman, as demanding in her own way as the saltiest football coach. “By the time I was through with (my girls), they were scared to death to act like heathens,” she once said.

Just as college football programs produce professional athletes, the program at Kilgore College has produced some Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders. Alice Lon, known to a generation of television viewers as the Champagne Lady on “The Lawrence Welk Show,” was a Rangerette. But turning out celebrities was never Miss Davis’ goal.

”By the time a girl leaves here after two years of long bus rides, hard work and performances, she’s usually got show business out of her system,” she told Sports Illustrated in 1974. “She’s ready to settle down. She’s dependable, because anybody who’s not dependable will not be in our line. She has good habits. She knows she can be courteous and a lady and still be herself. She has what some people call old-fashioned values. But she’s not worried about who she is.”

Davis enrolled in what is now Texas Woman’s University with thoughts of becoming a concert pianist but changed her major to physical education, graduating in 1927. At Greenville High School in 1928, she drew on her combined love of music, dance and athletics to create the “Flaming Flashes,” the first “dance and twirl” group. The Flaming Flashes used wooden batons from a local furniture maker along with various props, drums and bugles to create dances and marches. The Flaming Flashes were modeled after the first pep squads, which featured girls in abbreviated military attire and the occasional baton twirler.

In Kilgore, Miss Davis put together something else altogether. The uniforms set them apart from the old pep squads, and the high kick caught everybody’s eye. This was something different, and people took notice. The Rangerettes kicked off a drill team phenomenon that has seen tens of thousands of high school and college students join drill teams across the state and nationally.

That includes the Apache Belles, who hail from Tyler Junior College, also in East Texas, and who have developed a rivalry with the Rangerettes that is the drill team equivalent of the University of Texas and Texas A&M University football teams’ rivalry. You can start a lively discussion in either East Texas town by saying that one drill team is better than the other.

As might be expected with a group that has changed hardly at all in seven decades, there has been some criticism. A 1971 documentary film by Elliott Erwitt titled “Beauty Knows No Pain” (from the Rangerettes’ motto) gained wide distribution, including a 1973 broadcast on the CBS news program “60 Minutes.” Women’s rights advocates were quick to criticize Miss Davis and the Rangerettes as a troupe of sexist, mindless “Barbie dolls” whose routines were entirely inappropriate for a college curriculum.

Miss Davis would have none of it. She countered that the Rangerettes were confident, disciplined, poised and athletic and drew the kind of attention usually reserved for male athletes. Over time, the criticism has softened. Leibovitz’s book was meant as a collection of photographs featuring strong women, and she clearly thought that any woman who can touch the brim of her hat with her boot has to have some kind of physical strength (not to mention some serious flexibility) going for her. For a lot of us, the high kick the Rangerettes perform is akin in difficulty to slam dunking a basketball; both are things that most of us will never be able to do.

Erwitt, in the foreword to Lovett’s Kilgore Rangerettes, makes no mention of any social issues that might or might not be taken from his film. His loyalties are clearly with the unique subculture that is the Rangerettes.

”I suspect that modernity or fashion has not now changed, nor will it ever change, the way of life of the Rangerettes,” he writes. “Some Rangerette graduates have had daughters, and perhaps by now even granddaughters and great-granddaughters follow in their high-stepping footsteps. The tradition will continue. When a tradition is deeply rooted and special, it endures, and no one dares mess with it.”

——————–

Kilgore Rangerettes can be ordered from University of Texas Press through www.utexas.edu/utpress or purchased at many bookstores in Texas.

Clay Coppedge frequently writes history pieces for Texas Co-op Power.